Chapter 3: Agenda for Cooperation

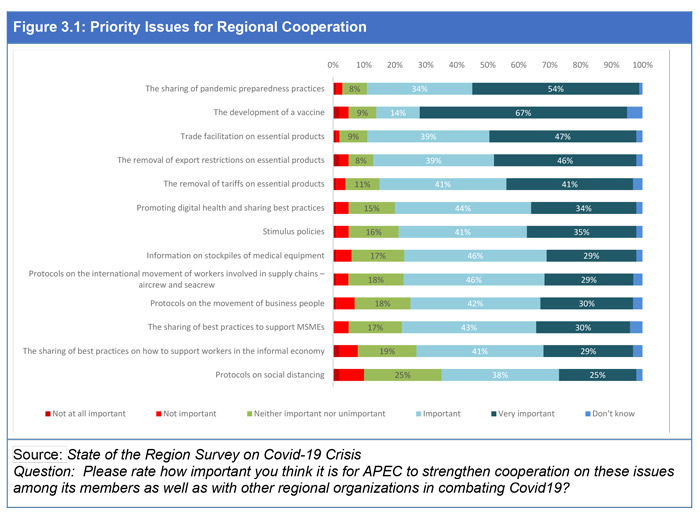

Previous chapters of this report have identified potential areas for regional cooperation in response to COVID-19. However, survey respondents were also asked for their priorities, and the top 5 issues were:

- The sharing of pandemic preparedness practices

- The development of a vaccine

- Trade facilitation on essential products

- The removal of export restrictions on essential products

- The removal of tariffs on essential products

Pandemic Preparedness Practices

While there has been some cooperation on these issues, this selection suggests a greater sense of urgency and need for engagement from the Asia-Pacific. In 2003 APEC established the Health Task Force (HTF) to help address health-related threats to economies' trade, focusing mainly on emerging infectious diseases, including naturally occurring and man-made diseases. It was upgraded to a working group in 2007.

Given APEC’s focus on trade and economic policy issues, the comparative advantage of its work in this area would be how pandemics impact trade and supply chains. This could build on existing work APEC has already undertaken such as the APEC Trade Recovery Program.

In considering work on pandemic preparedness, a link might also be built with APEC’s Disaster Risk Reduction Action Plan and ongoing work in other regional and international forum.

Vaccine Development

There is already considerable international cooperation on vaccine development, for example at the Global Vaccine Summit held on 4 June hosted by the UK, raised US$ 8.8 billion from 32 donor governments and 12 foundations, corporations and organizations to support the global fight against COVID-19.

Trade Policy Issues

The survey addressed three main trade policy issues for essential products: trade facilitation; the removal of export restrictions; and the removal of tariffs. All three were strongly supported. This underscores the message from research work by Evenett and Winters that the benefits derived from

“lowering import barriers on medical products and medicines during this pandemic are reduced if there is little available to buy at affordable prices as a result of the export bans imposed by trading partners. This matters now, for if the Global Trade Alert’s information is to correct, over 80 governments have taken steps this year to reduce or eliminate import tariffs on medical supplies and medicines.”

In short, the maximum gains for economies will come if all three actions are done simultaneously by as many parties as possible.

Trade Facilitation on Essential Products

The World Customs Organization has partnered with the WTO, UNCTAD, the CSSO, the GATF, IATA and ITC to develop a COVID-19 Trade Facilitation Repository that consolidates initiatives on trade facilitation into a unique and user-friendly database. It contains a useful listing of all such initiatives broken down by organization, type of measure and subject matter.

Export Restrictions on Essential Products

A key concern is the adoption of export restrictions on essential products. Both the International Chamber of Commerce in its letter to G20 Trade Ministers and the APEC Business Advisory Council in its letter to APEC Trade Ministers have called for their removal. Both G20 and APEC Trade Ministers responded somewhat to this call agreeing that,

“emergency measures designed to tackle COVID-19, if deemed necessary, must be targeted, proportionate, transparent, and temporary, and that they do not create unnecessary barriers to trade or disruption to global supply chains, and are consistent with WTO rules.”

The Removal of Tariffs on Essential Products

Interestingly the removal of export restrictions was ranked by respondents as more important than the removal of tariffs on essential products. The difference was small but noticeable, for all respondents to the survey, 85 percent of respondents rated the removal of export restrictions as very important or important while it was 82 percent for the removal of tariffs. Both the ICC and ABAC have called for their removal.

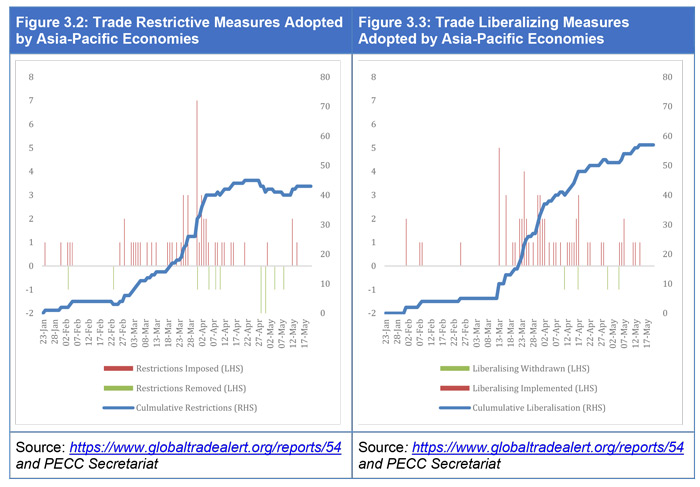

As seen in Figure 3.2 Asia-Pacific economies were adopting trade restrictive measures especially up until the G20 Trade Ministers virtual meeting on 30 March and the Special ASEAN Special Summit on Coronavirus Disease on 14 April. Those trade restrictive measures were not tariffs on imports but restrictions on exports – in the form of export bans, quotas, and licensing requirements. On the other hand, there have also been measures to liberalize trade mostly reductions in import tariffs and trade facilitation measures as shown in Figure 3.3.

While G20 and APEC Trade Ministers did not fully accept the ICC and ABAC recommendations on trade restrictions, they did agree that

if deemed necessary, must be targeted, proportionate, transparent, and temporary, and that they do not create unnecessary barriers to trade or disruption to global supply chains, and are consistent with WTO rules.

The lack of transparency and the notification process, however, are problematic for some. Rather than duplicate ongoing work in the WTO, APEC could seek to strengthen transparency in the notification process.

The more systemic problem, however, is that while governments are not going to give up the right to regulate scarce critical supplies in the time of an emergency, export restrictions are sub-optimal responses. They risk retaliation (emulation) by other economies, promoting panic buying and hoarding, and negative reputational effects that will reduce the appetite of investors to finance productive capacity in the sector.

As noted above in the section on risks, increased protectionism and trade wars continues to be seen as a top 5 risk to growth, according to respondents. In addition, for many economies, especially those in Southeast Asia, food security is a growing risk. This is likely a result of export restrictions imposed during the early phase of the crisis, especially before the G20 Trade Ministers Meeting, the APEC Ministers Responsible for Trade Statement on Covid-19 and the ASEAN Special Summit on Covid-19 (see Figure 3.2). However, regional economies have been working to restore confidence in the trading system, with the aforementioned high-level statements. An excellent example of building on those high-level statements is the Declaration on Trade in Essential Goods for Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic on 15 April between Singapore and New Zealand. This builds on the earlier Joint Ministerial Statement to ensure supply chain connectivity amidst the COVID-19 situation among nine economies.

The Declaration on Trade in Essential Goods for Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic has several important features, including an agreement to: remove customs duties on an agreed list of products; not impose export restrictions on the agreed products; and facilitate the flow and transit of the agreed products through their respective sea and air ports. An additional important feature of the declaration is an open accession clause. This is very much in the spirit of a Pathfinder Initiative that other economies could join especially given the complementarities that exist among regional economies in their trading patterns.

Information Sharing

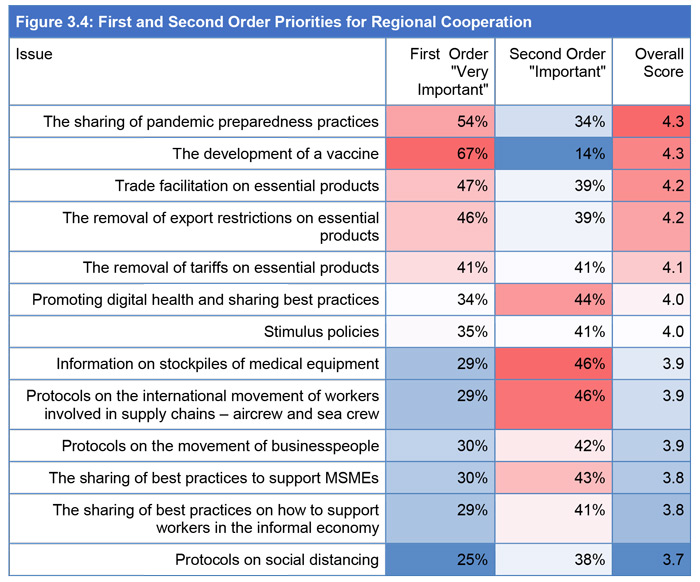

While the above section focused on the top 5 issues for regional cooperation identified by the survey, the top 5 issues by score were also the top 5 in order of percentage of respondents who ranked them as ‘very important’. Thinking of ‘very important’ as first order priorities and ‘important’ as second order priorities a different agenda for cooperation emerges. Noting that the question asked respondents to evaluate the importance of each issue on a scale from 1 to 5, Figure 3.4 shows the percentage of respondents that selected each issue as ‘very important’, ‘important’ as well as the overall score.

The first order of priorities – the top 5 areas of terms of the percentage of respondents who selected these issues as ‘very important’ are the same as those in the overall list which takes into account the weight on second order priorities. The second order of priorities based on the percentage of respondents who selected them as ‘important’ provides an interesting list of concerns on which there has been significantly less international cooperation and which constitutes a potentially rich area of work.

For example, while information on stockpiles of medical equipment ranked only 8th in the list of priorities, when viewed through the lens of ‘second order priorities’ it is the joint top of the list. As Hoekman et al argue

“governments need information systems that allow them to determine where supply capacity exists and that helps to understand the relevant supply chains. Firms generally will have information on supply options, but governments often will not have such information readily to hand. Both sets of actors need to be able to identify bottlenecks in the supply chain in real time and cooperate in addressing them.”

Cooperation centered on information exchange, dialogue and peer review may be more feasible. Such efforts should encompass the private sector given that the latter has a much better grasp of the relevant supply chains. Given APEC’s strong engagement with the private sector, it could pioneer and pilot such an information exchange.

Protocols on the International Movement of Workers involved in Supply Chains

The APEC Trade Ministers’ Statement on Covid-19 said they would work to

“minimize disruptions to the global supply chains…We will also ensure that trading links remain open and explore ways to facilitate essential movement of people across borders, without undermining the efforts to prevent the spread of the virus.”

As seen from the list of second order priorities, there is a need to work on protocols for the international movement of workers which include seafarers and marine personnel involved in international supply chains. Eighty (some say 90) percent of global merchandise trade is carried by some 96,000 ships. Those ships are crewed by about 1.8 million seafarers, 20 percent of whom are affected by lock-downs in transit hubs, suspended or limited flights and/or difficulties with entry and exit visas.

While appropriate international bodies have made progress on sets of protocols, the challenge seems to be in their socialization and implementation. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has published guidelines for protocols for safe crew changes but adoption has been slow. 73 One key concern expressed by industry as well as in qualitative comments in responses to the PECC survey is definitions of ‘essential workers.’

Box: APEC’s Key Role

“APEC has played a vital role in bringing the public and private sectors together to address critical issues. In times of COVID, more than ever, we need an agile and innovative mindset to put into practice solutions that disrupt the status quo. One concerns people connectivity protocols to ensure that the supply or value chains are sustained under this unprecedented period of fear. It is vital that APEC finds ways for essential workers like seafarers to travel from place of origin to a ship at port and back home to ensure that critical food, medicine, PPE products reach those in desperate need, and that global trade is undisrupted”

Doris Ho, former APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC) Chair and President and CEO of A Magsaysay Inc.

On May 11, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) noted its concern that

“the extensive and inconsistent border restrictions, in response to the global spread of the COVID19 pandemic, has severely disrupted the supply chain in delivery of essential medical supplies needed to respond to the pandemic.”

To facilitate flights while preventing the spread of the virus, the ICAO Collaborative Arrangement for the Prevention and Management of Public Health Events in Civil Aviation (CAPSCA) recommended the implementation of a “Public Health Corridor” (PHC) concept.

For APEC, rather than reinventing the wheel, CAPSCA links key international organizations involved in aviation as well as health. What is needed now is socialization and implementation of these practices as well as awareness of the broader implication of not implementing them – that is – chokepoints in supply chains.

As noted, while governments are facing a once in a hundred-year crisis, these supply chain issues are critical to ensuring the achievement of the objectives set out by APEC Trade Ministers in their Statement on Covid-19.

As with the ICAO and IMO protocols, these were developed in consultation and cooperation with a variety of different stakeholder groups. Emphasis will vary from location to location, but the general underlying challenge will be common across the region. With economies in the Asia-Pacific likely to be among the first to restart international travel, it would be valuable to take a cooperative approach. It will be highly problematic for the industry should governments across the world adopt a ‘spaghetti bowl’ of protocols and standards for international travel in a post-Covid-19 that will eventually have to be negotiated. This may be good for international negotiators but very costly for businesses and consumers alike.

Contact Tracing

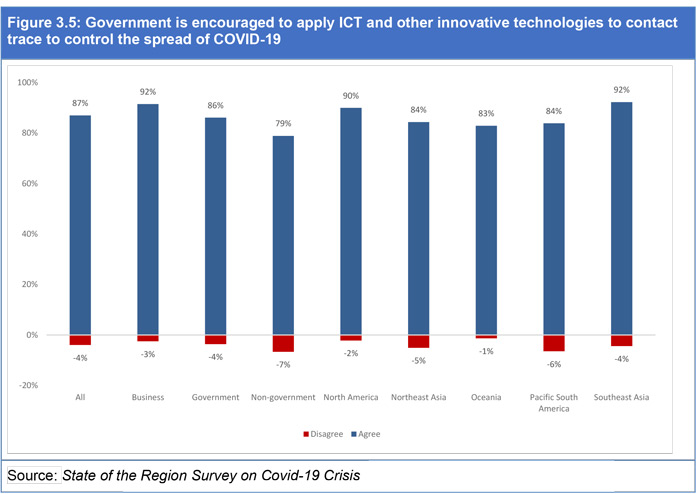

A third question on the role of government was also asked – on the application of information and communication technology to contact trace to control the spread of Covid-19, specifically whether the “Government is encouraged to apply ICT and other innovative technologies to contact trace to control the spread of COVID-19”. As seen in Figure 3.5, there was very widespread support across sub-regions and sub-sectors for the proposition. The “least” enthusiastic were respondents from the non-government sector.

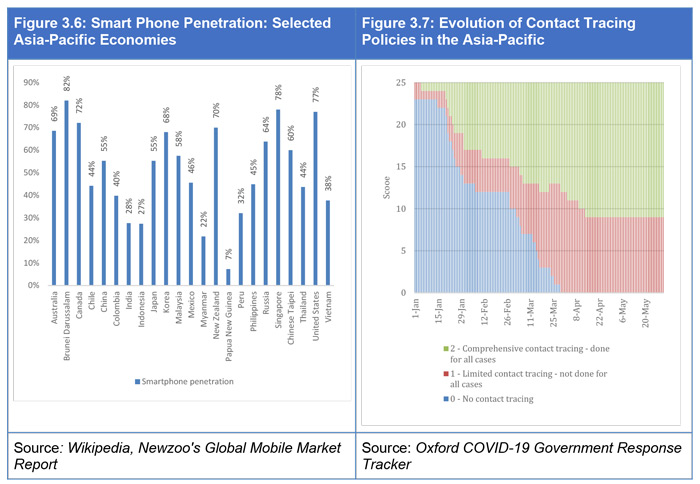

An even more important question is ‘how’ this is done. While the number of mobile subscriptions per capita for most Asia-Pacific economies is above 100, as shown in Figure 3.6, the penetration of smartphones while high is much more variable, which is a constraint on success.

Figure 3.7 shows how contact tracing policy has evolved for Asia-Pacific economies, from predominantly no contact tracing during the starting phase of the crisis to a mix of limited and comprehensive contact tracing. As shown in the chart, all economies in the region are now doing some form of contact tracing whether limited or comprehensive.

The scientific literature on the efficacy of the use of mobile applications for the use of contact tracing points to some useful lessons. For example, one widely reported story is that 60 percent of the population needs to be using a contact tracing up for it to be effective, however, the academic team behind that research has been at pains to clarify their research:

“There’s been a lot of misreporting around efficacy and uptake … suggesting that the app only works at 60%—which is NOT the case, it starts to have a protective effect (at) much lower levels”

according to Andrea Stewart, spokeswoman for the Oxford team told the MIT Technology Review.

Serious scientific work is being done to understand the efficacy of different technologies to address problems all governments are confronting. APEC with its convening power, especially in bringing together the business and academic communities together with government officials can play an important role in the sharing of this information. Given APEC’s non-binding and non-prescriptive cooperative nature this is an important role APEC can play.

For example, the GSMA Briefing Paper COVID-19 Digital Contact Tracing Applications distinguishes between two types of contact tracing apps:

- Location – typically collected from the GPS signal of the user’s device, giving the longitude and latitude coordinates of the device over time. Example – Safe Paths from MIT.

- Proximity – this approach traces the close proximity of pairs of people irrespective of where the proximity takes place. The most common approach is to measure the signal strength of Bluetooth signals from pairs of devices when the users are in close contact and without any knowledge of the geographic location. Example – TraceTogether in Singapore.

There are many other details that distinguish contact tracing apps. As different economies are seeking to implement their own, APEC, could play a role in assisting especially emerging economies by providing information on the various options available.

This issue of the management of contact tracing has important ramifications for exit policies and restoring confidence in the economy. As noted above, Japan’s plans to open travel with other economies is contingent upon, among others, the recording of movements on a smartphone application when in Japan. A major question is whether contact tracing apps adopted by economies need to ‘talk to each other’ or whether, to comply, travelers simply download the app for the place they are visiting just as they used to buy sim cards on entry.

Furthermore, while several databases exist on policy responses to the Covid-19 crisis, APEC could take the lead on delving deeper into specific aspects of those policy responses. As shown in Figure 3.7, all AsiaPacific economies are undertaking some form of contact tracing – the Oxford University database provides an ordinal scale:

- 0 - no contact tracing;

- 1 - limited contact tracing - not done for all cases; and

- 2 - Comprehensive contact tracing done

Given APEC’s recent focus and advances to address internet and digital economy issues since 2014, it could focus on whether economies are using contact tracing apps and develop its own scale for understanding differences in its adoption, sensitive to the unique circumstances among its membership. This would be a considerable contribution to the ongoing work among the global community struggling to deal with this issue.

Capacity Building for Recovery

As noted in the first section of this report, a major factor that will determine the duration of the crisis are the policies adopted by governments during and immediately after the crisis. While the prognosis of the regional policy community is towards more of a Swoosh-shaped recovery with considerably slower growth compared to pre-crisis levels, a more rapid recovery could be facilitated by the adoption of productivity and trade enhancing policies.

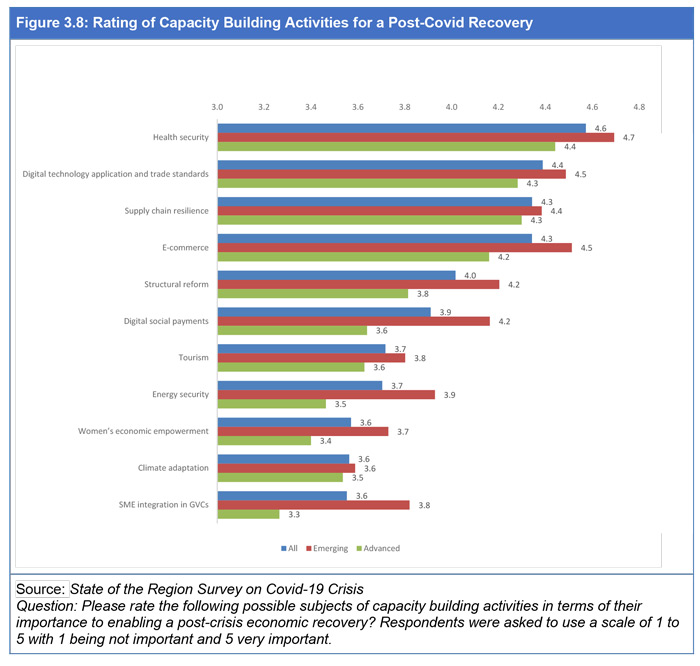

To develop a baseline of understanding of possible priorities for capacity building to enable a post-crisis economic recovery, respondents were asked to rate in terms of their importance a set of 11 activities.

In light of the Covid-19 crisis it is unsurprising that health security was rated most important to enabling a post-crisis economic recovery. This was true for emerging and advanced economies, business, government, and non-government respondents; as well as across sub-regions with the exception of respondents from Oceania. Respondents from Oceania ranked health security 3rd most important, the most important subject of capacity for them was supply chain resilience, which has become a large issue for them because of the lack of health security elsewhere.

Given that capacity building activities are mostly intended for emerging economies, Figure 3.8 provides the overall score for each activity as well as the results for emerging and advanced economies. As seen in the Figure 3.8 emerging economies place a slightly higher degree of importance on all activities compared to those from advanced economies. For health security, the score given by respondents from emerging economies was 4.7 while those from advanced economies was 4.4.

Respondents were most split over the ranking for the second most important activity. Overall digital technology application and trade standards placed second with a score of 4.4 and 53 percent of respondent rating it as very important. However, while it was second ranked for respondents from Oceania and Northeast Asia, it ranked third for those from Southeast Asia and Pacific South America and North America.

The third most important was supply chain resilience. While ranked 4th by respondents from emerging economies with a score of 4.4 it was ranked second by those from advanced economies with a score of 4.3. Respondents may have different interpretations of the nature of resilience, which we discussed above.

The fourth most important capacity building activity was e-commerce. Interestingly, this was ranked second most important by respondents from emerging economies with a score of 4.5 and fourth by those from advanced economies with a score of 4.2. The experience of COVID-19 has drawn attention to the relevance of digital technology for both goods and services producers.

Cross cutting many of these activities is the role of digitally enabled services, which can contribute for example to supply chain resilience and e-commerce. Analytical work referenced earlier shows higher fintech tends to lead to greater women’s economic empowerment and digital social payments, which have facilitated the targeting of fiscal stimulus measures, are also often seen as a way to accelerate onboarding of people into the financial system. Not surprisingly then, digital technology application also ranks highly in this list of items for capacity building.

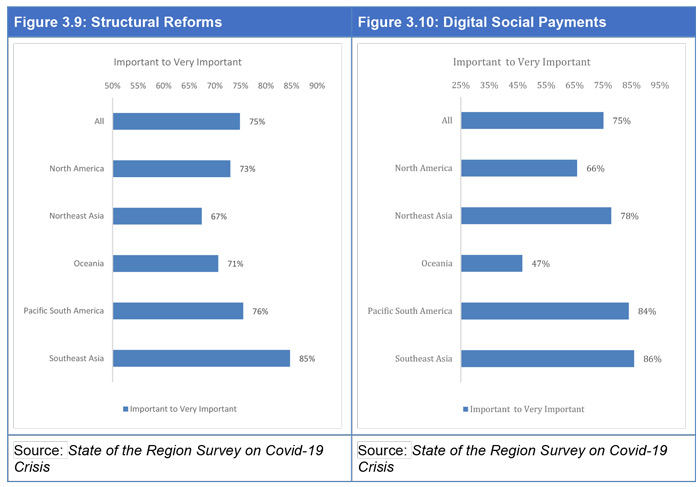

Structural Reforms

The fifth priority for capacity building for the post Covid recovery was structural reform. Both emerging and advanced economy respondents ranked structural reform in fifth place with scores of 4.2 and 3.8, respectively. There was remarkable convergence on the importance of structural reforms to the post-Covid recovery with government, business and non-government respondents all ranking them in fifth place.

However, as seen in Figure 3.9, respondents from Southeast Asia gave a significantly higher level of importance to structural reforms than other respondents.

PECC’s work on the post-2020 vision for APEC gave a high priority to the structural reform agenda noting that while trade liberalization has been central to growth in the APEC region, the fundamental norms that have historically underpinned liberalization are no longer sufficient by themselves to drive growth and trade forward. Maintaining future momentum will also be critically dependent on meaningful structural reform in member economies, to:

- Boost productivity through operation of open, well-functioning, transparent and competitive markets;

- Encourage the use of economic instruments to support sustainability objectives;

- Identify and remove barriers to full economic participation by all segments of society; and

- Strengthen social safety nets

In the post-Covid-19 context, structural reforms become even more important to ensure full access to and participation in the delivery of effective and efficient healthcare to citizens.

There are similar differences regarding capacity building on digital social payments. While very high percentages of respondents from Southeast Asia and Pacific South America rated capacity building activities for digital social payments as important or very important, 86 and 84 percent respectively, considerably lower percentages of respondents from more developed sub-regions rated this as an important issue. The ability to use digital payment systems was a lifeline for millions during the crisis, as experience around the world has shown, the onboarding process for many of the systems take place through social welfare payments. These systems also increase transparency and accountability. Work cited earlier by the IMF has found that

“during the COVID-19 crisis, access to government electronic systems that are well integrated with digital financial services platforms such as fintech firms, mobile money companies, and digital banking are proving to be critical in providing wide-reaching policy support promptly and without physical contact. If they are not easily accessible or not well integrated, fiscal support announcements—no matter how large—will fail to reach those most vulnerable and needy. Thus, the fiscal response should go hand-in-hand with investment in digital infrastructure, and importantly promoting digital and financial literacy to ensure greater digital inclusion.”

Interview with Cindy Hook, Chief Executive, Deloitte Asia Pacific

As CEO of Deloitte Asia Pacific, what stands out to you about the region? There’s no doubt that the Asia-Pacific is a diverse region, but the level of cultural, economic, political, and social diversity is even greater than I had expected. It’s one of the things that makes this region so unique and exciting. Yet despite this diversity, there is a higher level of collaboration and cooperation among businesses and governments than I’ve seen elsewhere.

The other thing I have observed is the tremendous opportunity for growth. You hear about the “Asian Century,” the shift from “West to East,” and predictions that our region will deliver 60 percent of global growth in the coming decade78 – so I came in expecting there would be a lot of potential. But once you start living and working in the region, you get a much deeper sense of how far Asia has come in the past 50 years, and how much more room there is for further gains.

I have also seen a high degree of confidence in the ability of the Asia-Pacific to reach higher levels of economic success and global influence. Of course, we will require greater levels of collaboration to tap into these potential opportunities.

What impact is COVID-19 having on the Asia-Pacific? The impact of COVID-19 is profound in Asia, as it has been everywhere in the world. This is likely to be one of the most defining moments of our times. But the question is: will the long-term impact be positive or negative?

For many reasons, I believe the Asia-Pacific will emerge stronger from the pandemic. The region overall was more prepared and has weathered the health crisis quite well. This will enable the Asia-Pacific to emerge from the economic crisis faster and stronger than other regions. We are already seeing this in China, for example, where manufacturing activity has continued its expansion after a sharp drop in early 2020.

The crisis is also likely to accelerate a range of fundamental business and societal transformations that were already underway. Things that would have happened over the next five to 10 years will now happen in the next one to three years. These include the digitalization of businesses and the move to the cloud, the reformation of supply chains to ensure resilience, and changes to how and where work gets done – with flow-on effects for inclusiveness, gender equality, and sustainability.

This acceleration is exciting and will create opportunities for those who can adapt and innovate. However, it will also be challenging for many. This will lead to an even greater role for governments as they support society through these transformations.

How should organizations be responding to the crisis? In a crisis, the human tendency is to retreat to your home ground. And with all the mobility restrictions we are facing, this has literally been the case. Yet if you look at the course of history, economic prosperity has come to those who have demonstrated an outward focus.

So, there is no better time to embrace globalization over nationalism. The saying “change or die” is also more relevant than ever. Those organizations that seek to just keep doing what they always did will miss the opportunities that inevitably arise from this crisis.

Will leadership need to change as a result of the pandemic? This pandemic will certainly be the biggest challenge of most leaders’ careers. The next couple of years will be incredibly demanding for businesses and governments as they navigate their way through the health and economic recoveries. Many attributes of great leaders – vision, authenticity, purpose, strategic thinking, resilience, and fortitude – will remain important.

Leaders need to consider what the new normal will look like and how that changes aspirations, priorities, and strategic choices. Most businesses will have to shift their strategies coming out of the crisis, and for some it will be a complete pivot. Leaders who are strong agents for change will have an advantage in these times.

One hope I have is that more leaders in government and business will use this opportunity to make a true commitment to sustainability and combatting climate change as part of their strategic agendas. I do think we are seeing a real change as businesses find a new balance between profit and purpose, and place more focus on sustainability. It’s clear that growth and development are no longer just about economics, so it would be great to see a new level of commitment to sustainability reflected in everyone’s plans.

Will multilateralism and APEC become more or less important in the years ahead? Both will definitely become more important, and significantly so. Our biggest global challenges – such as COVID-19 and climate change – have no respect for borders and must be addressed in a coordinated way, globally and regionally. This means it’s more important than ever to maintain multilateral relationships.

Unfortunately, we haven’t always seen such a coordinated response in practice. This underlines the need for us to work with and support international forums. APEC is certainly one of the most important of those and vital for sharing ideas, recommending best practices, and shaping collaborative actions.

I would encourage leaders to use this time of tremendous disruption to think big and pursue bold visions, not just incremental change. The Asia-Pacific is incredibly dynamic and diverse, so it’s ideally placed to play a leadership role as the world moves beyond this crisis and finds new ways to succeed.