Chapter 2: From Survival, Stimulus and Exit Strategies

A major concern as the crisis has unfolded is its multi-dimensional nature: as a health and humanitarian crisis, as an economic crisis, and with the risk of a financial crisis as well. Governments have acted swiftly to abate the impacts in these areas, that is: by containing the spread of the virus, injecting massive unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus to support those in need and restoring some semblance of confidence in markets.

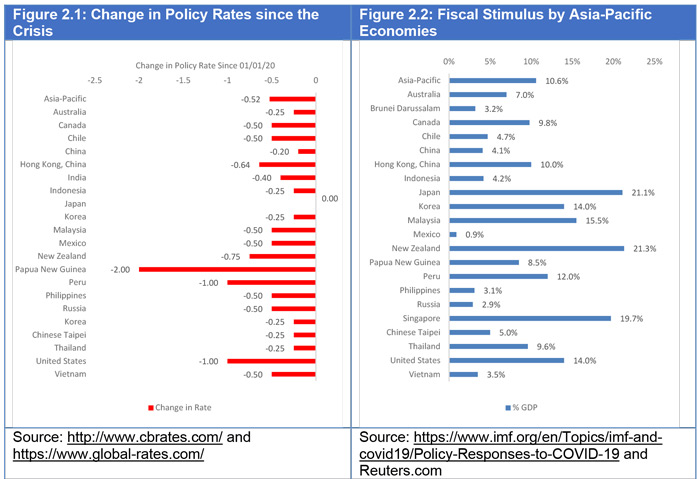

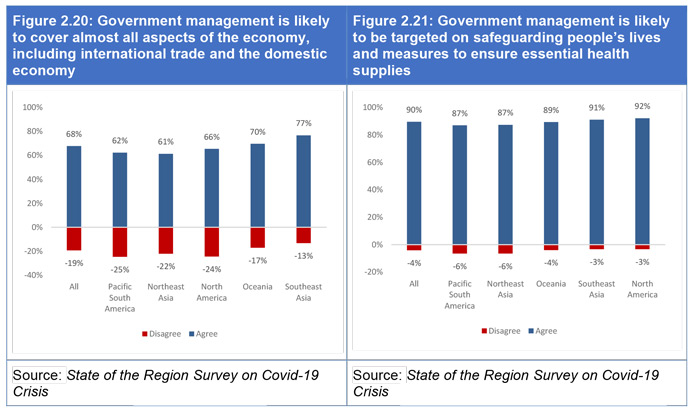

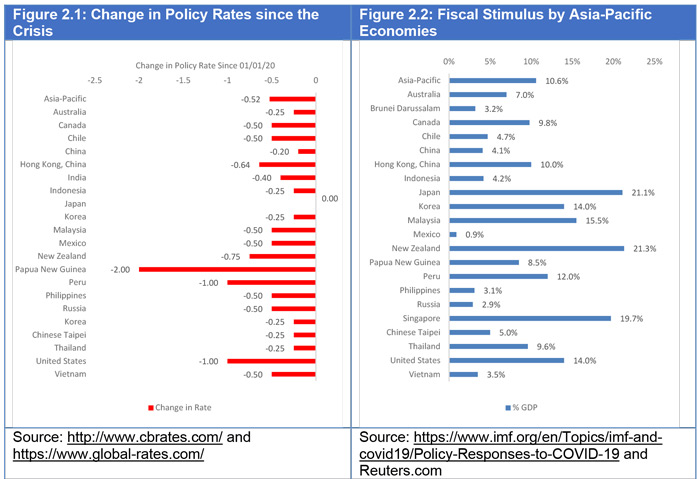

What has prevented a freefall in economies have been massive stimulus measures adopted by governments. As seen in Figure 2.1, governments across the region have cut interest rates by an average of 0.5 points, this is at a time when they were already at historic lows following the long and drawn out recovery from the Global Financial Crisis. But Central Banks did act to cut policy rates and as seen later, regional currencies have recovered some of their earlier losses against the US dollar.

Fiscal responses and Financial Markets

More importantly governments have been implementing fiscal stimulus packages to assist people and businesses struggling through these difficult times. As shown in Figure 2.2 these stimulus packages vary in their magnitude – as a percentage of Asia-Pacific GDP they are approximately 10.6 percent of the economy. Their total value is $5.4 trillion, compared to an estimate of the global total of US$11 trillion 21 , but this does not include central bank funding. Estimating the amount of stimulus is difficult as it includes what the IMF refers to as ‘above the line’ – revenue and expenditure measures as well as ‘below the line’ measures - loans and equity injections. Other examples of complementary measures have included

easing insolvency requirements, arranging rent and bank loan reductions or repayment deferrals. 22 In spite of the massive stimulus, there remain deep concerns in financial markets about the future trajectory of growth and jobs.

International coordination and cooperation would help restore confidence, as it did during the Global Financial Crisis, as well as build a sense of direction to support future growth.

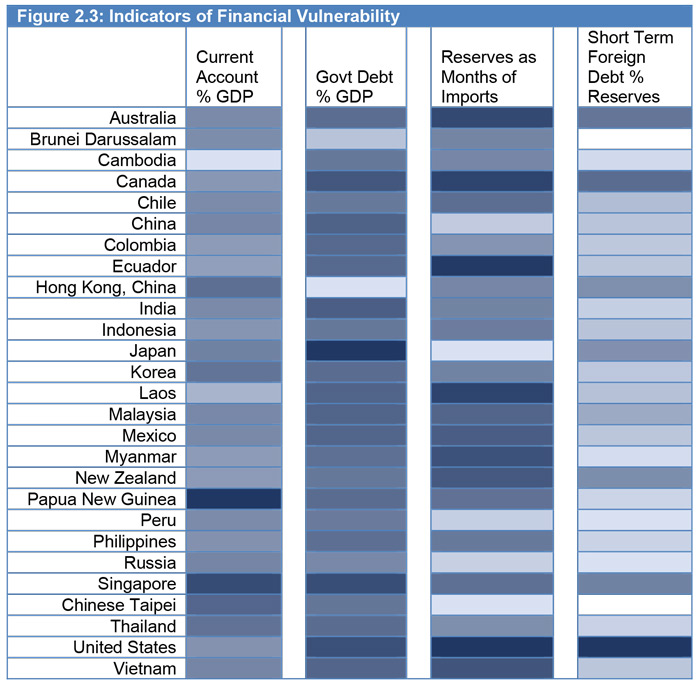

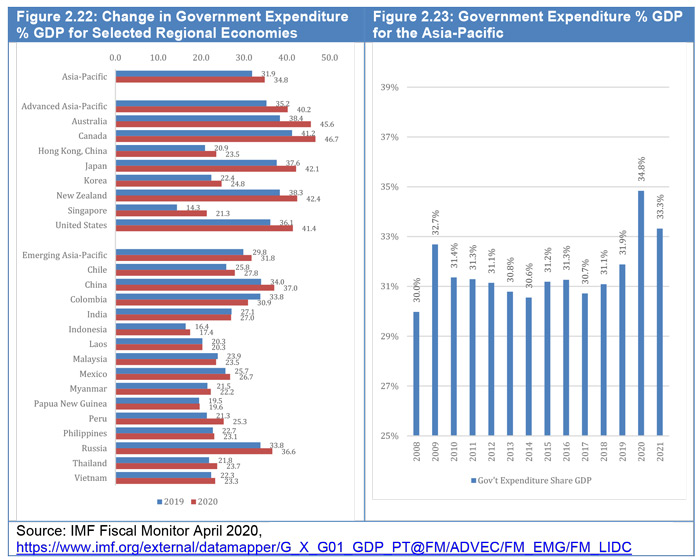

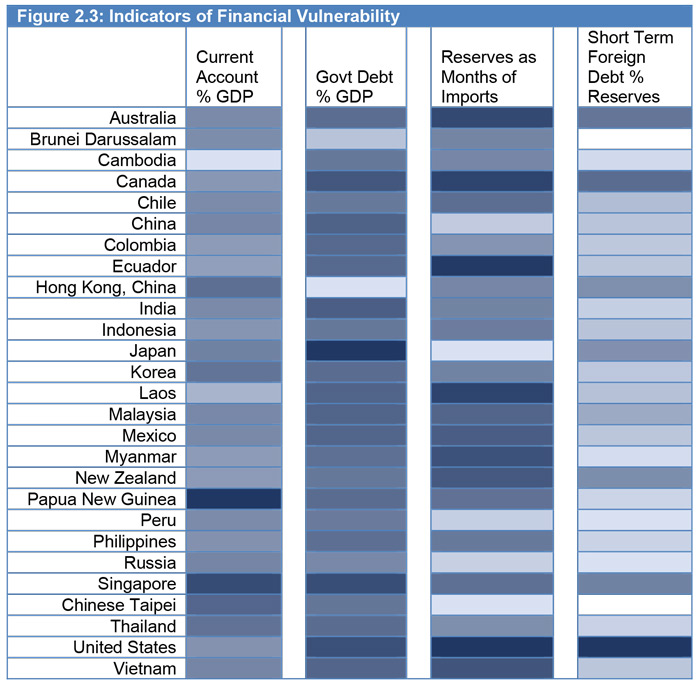

Figure 2.3 is designed by a numerical approach to some key indicators of financial vulnerability: current account balance as a percentage of GDP; government debt to GDP; reserves as months of imports and short-term foreign debt as a percentage of reserves although we omit the actual numbers for simplicity. The darker the bar the more ‘vulnerable’. The assessment is made relative to others within the group rather than compared to a global norm. Many other many factors come into play. But as seen in Figure 2.3, relative to their advanced economy peers, emerging economy have relatively strong financial conditions, eg lower public debt to GDP ratios. Moreover, since the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98 many emerging Asian economies have amassed significant reserves well-beyond the traditional benchmark of 3 months of imports. Beyond that, in comparison to advanced economy peers, short-term debt to total reserves are significantly lower. The region remains scarred by two financial crises which may contain the appetite of policy-makers to go beyond certain limits in the advent of capital flow reversals. While regional economies do not suffer from significant debt burdens, coordination and cooperation would support a bolder approach to fiscal stimulus on the part of the region’s emerging economies. They would be more confident of the impact of their fiscal measures.

There are regional mechanisms to facilitate this cooperation. The ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) was established following the 1997-98 crisis with a mandate to conduct macroeconomic surveillance. Participants in the APEC process will recall the disappointment of members following the 1997-98 crisis and therefore may consider what it might do to assist, given the developments that have taken place since then. APEC officials seek to fulfill the mandate from the APEC Trade Ministers Statement on Covid-19 issued on 5 May to develop a

“coordinated approach to collecting and sharing information on policies and measures, including stimulus packages for the immediate responses to the economic crisis and long-term recovery packages”

In this context, East Asian discussion and cooperation that is based in ASEAN+3 mechanisms such as AMRO could usefully be extended to the APEC Finance Ministers’ process. While not necessarily including all APEC members such a dialogue would help to avoid duplication of effort and help to identify gaps in information and data necessary for strengthening policy cooperation and coordination.

Feedbacks from financial markets, in response to both the COVID events and the fiscal policy responses, including longer term risks associated with the growth of debt, are also important to consider in the transition to recovery.

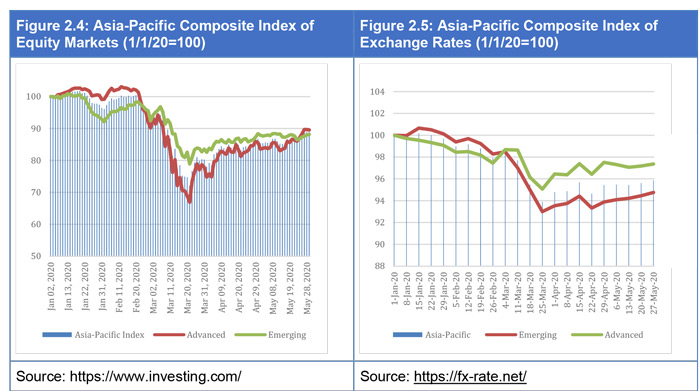

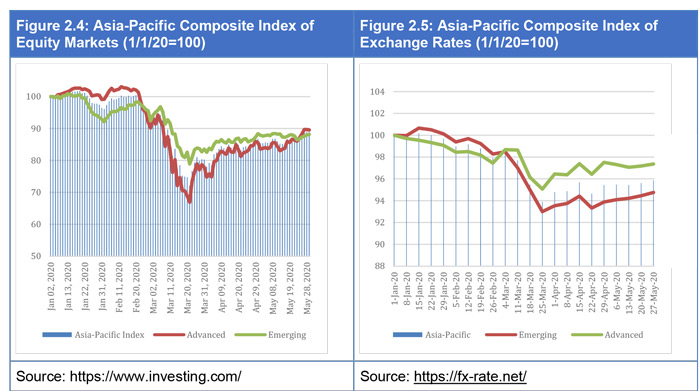

Regional stock markets had plunged by as much as 28 percent during the third week of March (Figure 2.4). The drop was more extreme for the region’s advanced economies which fell by over 30 percent compared to the region’s emerging economies stock markets which fell by a GDP weighted average of 20 percent. However, since those depths in March, confidence has started to restore due to the measures taken by governments, and although recovering somewhat equity markets are still down since the beginning of year by an average of 12 percent. In addition, markets remain highly volatile and there are significant risks of financial contagion between different segments of the market and among economies. There appears to be a current lack of connection between ‘Wall Street and Main Street.’

A similar story is seen on the foreign exchange front. While exchange rate adjustment is one source of resilience for economies, of more immediate concern is a drop in the value of a currency due to capital flight which has been a considerable concern especially for emerging market economies. A basket of 20 Asia-Pacific currencies weighted for goods and services trade was at its lowest against the US dollar on 25 March having lost 6 percent in value since the beginning of the year. Emerging markets have fared slightly worse losing 7 percent against the US dollar compared to the region’s advanced economies which lost 5 percent. However, as with equity markets, currencies have also rebounded somewhat since their nadirs, and stand at around 4 percent lower from their value at the beginning of the year.

According to the data reflected in Figure 2.3 many of the region’s emerging economies have relatively strong positions vis-à-vis key indicators of financial vulnerability, However, East Asia’s debt is still large in absolute terms, and growing with the fiscal stimulus recently applied. 24 Also the valuation of reserves in Figure 2.4 can shift quickly, since about 10 percent are in equities and 7 percent in bonds. 25 However, as noted, the historical scarring of the last 25 years may leave many policy-makers wary of greater exposure at a time when markets are so volatile. The IMF urges caution as well, noting the never-before-seen levels of debt relative to global GDP (over 100 percent). 26 It argues for consideration to be given to sustainable fiscal balances through plans in the medium term to promote growth, raise revenue and add to efficiency in spending (in both respects efficiency improving measures are feasible, including carbon taxes (former) and removing subsidies (latter)).

Over the longer term but of significant concern for policy-makers today is the issue of the impact of crisis on interest rates. Currently low rates support the use of debt to finance the fiscal stimuluses. The additional government spending required to support economies during the crisis has in most cases been financed by increased public debt. Gavin Goy and Jan Willem van den End review the literature on this issue and find alternative viewpoints – some like Jorda discussed below expect lower long-term interest rates while others such as Summers point to the increased supply of government bonds having an upward effect on the equilibrium interest rate. They argue that

“to bolster potential growth, it is important that public spending supports private investments and productivity by creating growth enhancing conditions, e.g. by spending on infrastructural projects that would elicit private activities.”

Krugman argues that debt sustainability is not an issue as long as interest rates remain below the nominal growth rate – that is very much dependent on effective returns on investment. There are other issues to consider such as social and public goods but in terms of debt sustainability, low interest rates cannot be taken for granted.

G20 Central Banks have agreed to

“use all available policy tools to support the global economy, boost confidence, maintain financial stability and prevent deep and prolonged economic effects”,

But risks remain, including those of contagion in financial markets and, over the medium to long term, of secular stagnation, as evident in the results of the PECC survey.

With respect to contagion risks, because of the nature of the role of the US dollar as the global reserve currency, one action that would prevent currency outflows for those with floating exchanges rates is to establish and extend swap arrangements. The Federal Reserve has said that these agreements could

“help lessen strains in global U.S. dollar funding markets, thereby mitigating the effects of these strains on the supply of credit to households and businesses, both domestically and abroad”.

28 Indonesia for example is in talks with central banks around the region on ‘second lines’ of defense. 29 In the same way that information sharing should be integrated in forums across the region, so too is it timely to have broader discussion of the adequacy of the financial safety net – including IMF financial resources and the connection between regional and global financial crisis mechanisms – in a range of Asia-Pacific forums. Again, East Asian discussions and cooperation that is based in ASEAN+3 mechanisms, in this case such as the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM), could also usefully be extended to the APEC Finance Ministers’ process. One of the biggest challenges in strengthening the global safety net is in obtaining U.S. agreement to extend the financial resources of the IMF and improve its governance (while maintaining a U.S. veto). APEC is one forum where Asia can have this necessary conversation with the United States.

The Mechanics of Leaving the Lockdown

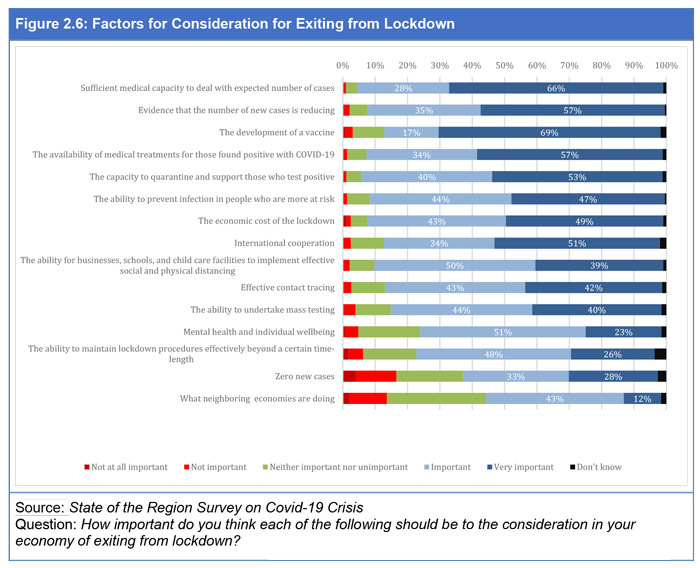

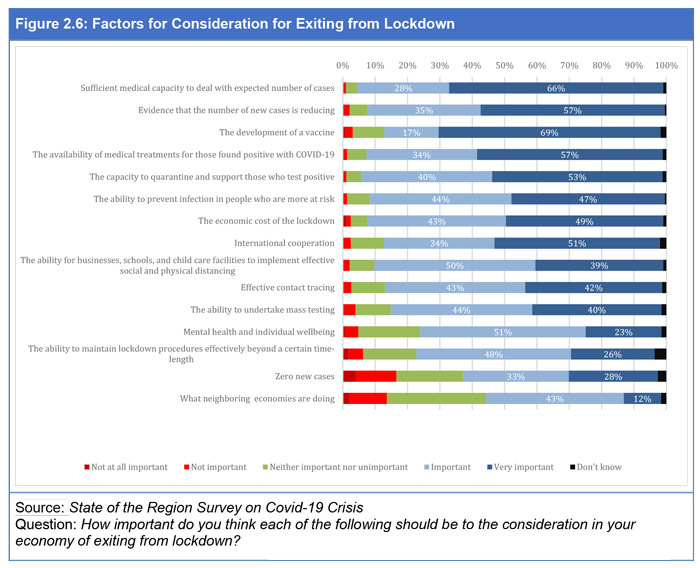

Given the heterogeneity of the Asia-Pacific region we wanted to understand whether there would be large differences between members of the policy community from different economies on the factors to be considered for their economy’s exit from lockdown. A list of 15 issues was selected and respondents were asked to give their opinion on the importance of each of them. One hypothesis that we wanted to test was whether the economic cost of lockdown policies would be a higher consideration for emerging economies compared to advanced economies.

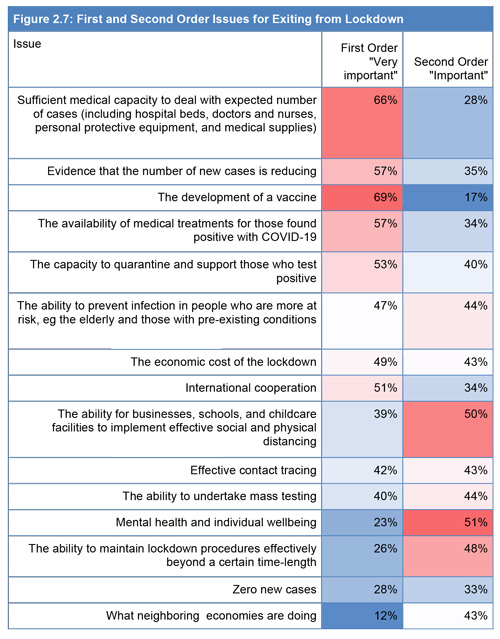

Figure 2.6 above shows the list in order of their importance. The top 5 (where relatively higher weight is given to ‘first order issues’) were:

- Sufficient medical capacity to deal with expected number of cases (including hospital beds, doctors and nurses, personal protective equipment, and medical supplies)

- Evidence that the number of new cases is reducing

- The development of a vaccine

- The availability of medical treatments for those found positive with COVID-19

- The capacity to quarantine and support those who test positive

This is followed by a group of three other items which attracted relatively high support. These included the ability to prevent infection in people who are more at risk, which is also related to another on this list which is the cost of the lockdown. A more targeted approach to the former may ameliorate the burden of the latter. But also in this group of three is international cooperation. Indeed, a theme of this report is its value in assisting the response to the crisis, and our respondents concur with that view.

The capacity to achieve goals related to social distancing, to test and also to contact trace and to isolate those affected are not common talking points in the discussion of exit strategies. The relaxation of restrictions on people movement in the short term will depend on their operation in many economies. These aspects are also being given greater attention as some economies have attempted to relax restrictions, only to see infections rise again. It is of interest that survey respondents put these measures in a third tier of priorities, following public health matters, economic consequences and international cooperation.

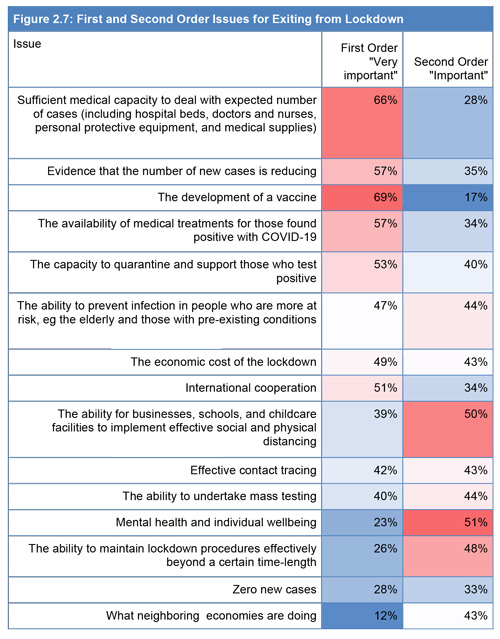

Figure 2.7 below provides a different way of thinking about these factors. The darker items shaded red are those with higher percentages of respondents selecting as very important in the first column or important in the second column.

Overall, health considerations remain the top priority for respondents, prior to relaxation of lockdown conditions, for example, the capacity of the health care system, support for those who are ill or at risk, quarantine capacity, and even the development of a vaccine. Items such as the economic cost of these measures or the extent of international cooperation are middle ranked. Aspects such as tracing and testing are further down the list.

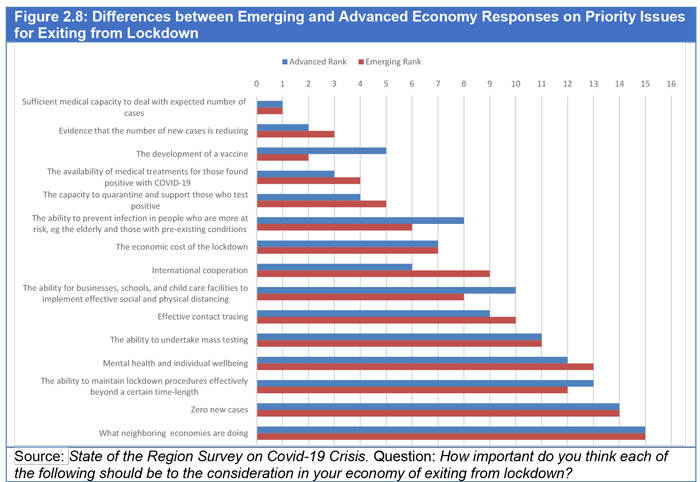

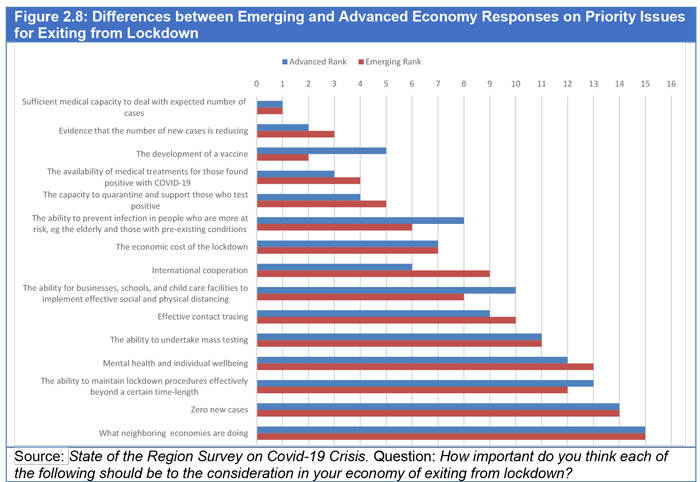

Figure 2.8 which shows the results for respondents from advanced and emerging economies; there was a remarkable degree of convergence. Because of the relative similarity in overall scores, to give greater contrast, the chart shows how each sub-sector ranked the issue in terms of its importance.

There were four issues on which respondents from emerging and advanced economies had a different perspective:

- Development of a vaccine: respondents from emerging economies ranked this as 2 nd most important while those from advanced economies ranked it 5 th

- International cooperation: respondents from advanced economies ranked it 6 th highest while those from emerging economies ranked it 9 th .

- Ability to prevent infection in people who are more at risk: emerging economy respondents rank this 6 th highest while those from advanced economies 8 th .

- The ability for businesses, schools, and childcare facilities to implement effective social and physical distancing: this was ranked 8 th most important for emerging economy respondents and 10 th for those from advanced economies.

Other than these four issues, the gap between advanced and emerging economies was no more than one place in ranking.

The issues of medical capacity generally remain a primary consideration. As has been noted, economies around the region and the world were not sufficiently prepared for a pandemic of this magnitude. Sadly, this was well-known even before it happened, an assessment of pandemic preparedness done just last year notes that

‘no [economy] is fully prepared for epidemics or pandemics. Collectively, international preparedness is weak. Many [economies] do not show evidence of the health security capacities and capabilities that are needed to prevent, detect, and respond to significant infectious disease outbreaks. The average overall Global Health Security (GHS) Index score among all 195 [economies] assessed is 40.2 of a possible score of 100’.

30 In the midst of the crisis some economies have been building the capacity to deal with the expected number of cases. This has involved building temporary hospitals in a record number of days, 31 and supply chains have responded quickly to the need to supply more ventilators, 32 personal protective equipment, 33 face masks, 34 and hand sanitizer. 35 It turns out that many industrial processes are relatively malleable.

While factories can be retooled, training medical personnel is much harder. This has led to some pressures on mobility of people as well. For example, during the crisis the Philippines issued a ban on medical personnel leaving. Given that Filipinos account for a substantial proportion of nurses in many economies in the world, this could have been problematic but eventually the order was rescinded.

This approach reveals, for example, the importance as a secondary issue of ‘mental health and well-being’. Only 23 percent of respondents selected it as a very important issue for consideration but 51 percent selected as important. Under the weighted scoring system, it ranked 14th out of 15, but it was ranked highest as a second order issue. This approach helps to highlight an important concern for policy-makers in areas still under lockdown to take into account. Even now hotlines for mental health report record increases in calls around the world.

Long Term Impact on Business

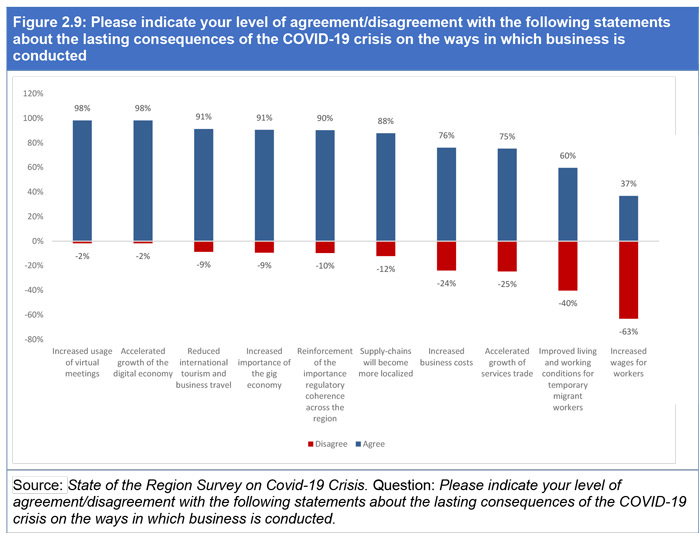

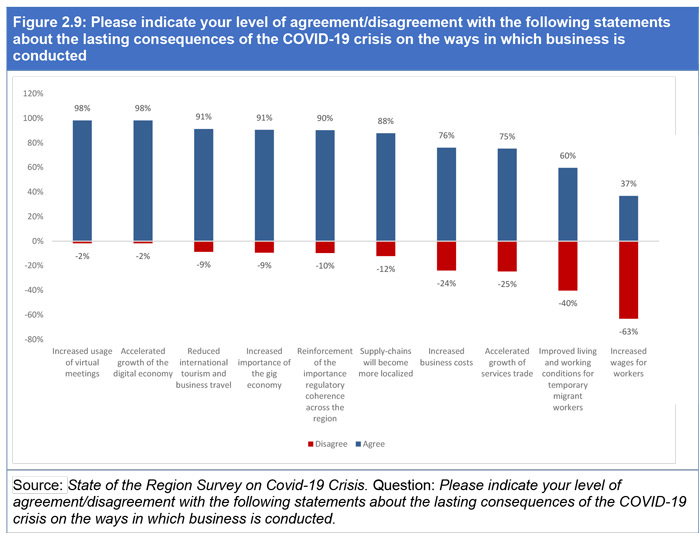

To understand perceptions about the possible lasting consequences of the Covid-19 crisis for business in the region, respondents were asked to give their levels of agreement or disagreement on a series of propositions.

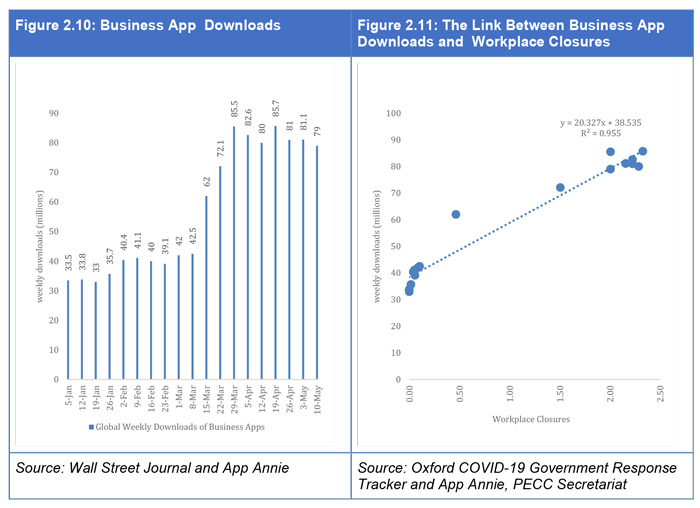

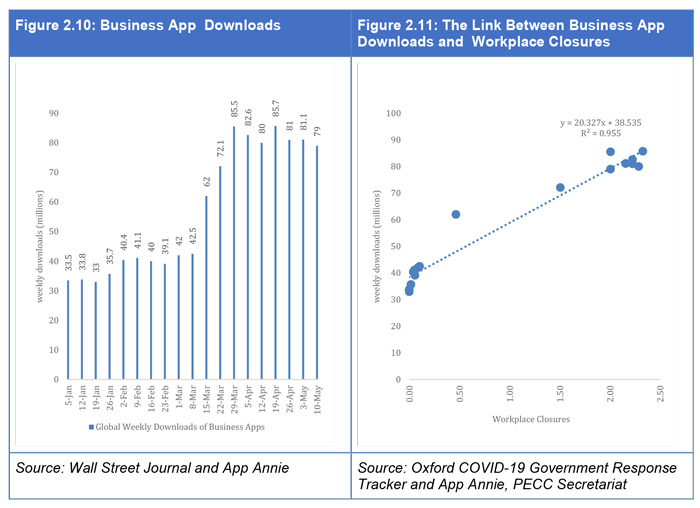

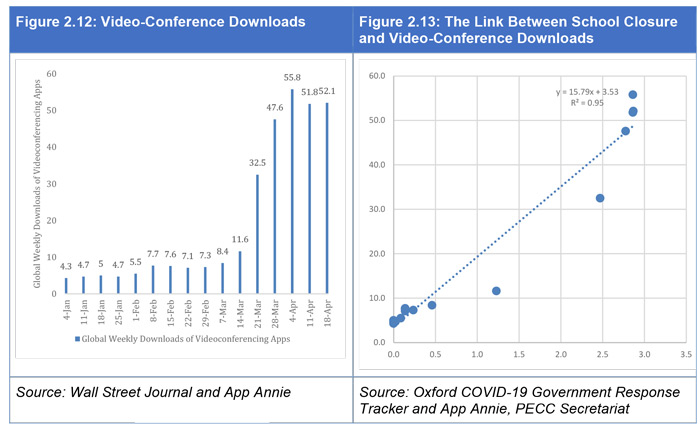

As shown in Figure 2.10 and 2.12, given the very rapid acceleration of video-conferencing and digital technology during the crisis it is also not surprising that there was almost unanimous agreement on the increased usage of virtual meetings and the accelerated growth of the digital economy, along with a reduction in travel.

There is a strong expectation that supply chains will become more localized, and that the value of regulatory coherence will rise in this context. There is some expectation of the growth of services trade and of a rise in business costs, although a quarter of respondents expect the opposite in each case.

There were mixed results on outcomes for workers. This finding is not surprising given the impact that the crisis has had on unemployment and indeed on wages with many workers being asked to take pay-cuts. However, longer-run studies of the impacts of pandemics on wages over the past 700 years show on average a deviation of 5 percent above the baseline for a period of years after the end of pandemic.37 Other impacts include increased precautionary saving and lower long-term interest rates.

The Accelerated Growth of the Digital Economy

Figure 2.10 shows the number of weekly downloads of business apps. At the beginning of the year the weekly average was around 33.5 million downloads, by February it had grown to above 40 million and then as economies around the world implemented lockdown policies and closed offices the download of business apps skyrocketed to above 80 million a week in April. While global trade has fallen sharply, the digital economy has grown exponentially. Can this shift ameliorate the fall-off in more traditional economic activity?

The relationship between the growth of the digital environment and the closure of traditional workplaces is illustrated in Figure 2.11. The values in the tracker are as follows:

- 0 - No measures

- 1 - recommend closing (or work from home)

- 2 - require closing (or work from home) for some sectors or categories of workers

- 3 - require closing (or work from home) all-but-essential workplaces (eg grocery stores, doctors)

The figure shows the positive relationship, as expected, between closures and downloads. The global mean average for the workplace closures peaked (so far) at a value of 2.33 with 57 percent of economies in the group at level 3, 28 percent at level 2, 7 percent at level 1 and 9 percent at level 0.

While much of humanity has been locked down, the digital economy has been a lifeline for millions if not billions. Demand for access to the internet has risen sharply. Companies like Netflix and Google have had to reduce the quality of their streaming content to reduce congestion on the internet. 38 This experience highlights the value of the achievement of APEC’s goals on the Internet and Digital Economy Roadmap. For example, two of the key focus areas in the Roadmap are especially relevant at this point:

- Development of digital infrastructure

- Achievement of universal broadband access

Information from the private sector, particularly digital companies can be critical in the response to the crisis, for example, in providing more targeted and effective support to households and to vulnerable companies, especially micro and small and medium companies. In a case study of China’s response during the crisis, the digital economy was found to have the following advantages:

-

- Relatively complete credit rating systems specifically for SMEs and individual e-commerce sellers through the use of big data;

- Real-time monitoring of debtors with the help of big data, blockchain finance, supply chain financing and other technologies;

- Lending practices that are free from geographical restrictions that can provide SME credit on a larger scale; and

- The ability to complete credit transactions remotely online, which helps prevent and control the epidemic.

One particularly important aspect of the digital economy during the crisis has been the ability to complete contactless transactions, essential when social distancing measures are in place to control the spread of the epidemic. This was possible in China with the high levels of online banking/digital wallet adoption.

A recent report from the IMF confirms these findings, arguing that

“during the COVID-19 health crisis, digital financial services can and are enabling contactless and cashless transactions. Where digital financial inclusion is advanced, they are helping facilitate the efficient and quick deployment of government support measures, including to people and firms affected by the pandemic.”

However, the same report affirms the importance of making progress on the agenda APEC had outlined in its Roadmap on the Internet and Digital Economy, warning that while fintech can lead to more inclusive outcomes, unequal access to digital infrastructure, lack of access to mobile devices amongst others could lead to new forms of exclusion.

There is scope to use private sector data for the analysis of policy responses. A team at Harvard University is now using anonymized data from private companies to understand the impact of the crisis at a highly disaggregated level of locality and income groups. The team has been able to demonstrate the impact of the crisis on consumer spending as well as the efficacy of stimulus policies in almost real time. A very important finding for policy-makers concerns the drivers of the change in demand. The authors report that

“…it is the fear of Covid-19 itself, not executive orders restricting business activity, that are the primary cause of reduced economic activity and job loss.”

In short unless the health crisis is solved, even lifting the lockdown condition will not restore economic growth. Amongst the authors’ public policy recommendations is that

“the only way to drive economic recovery is to invest in public health efforts that will restore consumer confidence and spending.”

This finding coincides with the PECC survey findings above on the most important conditions for exiting from lockdown.

While limited to the United States, the Harvard University authors believe that much of the methodology could also be replicated in emerging economies as well since the data come from internationally active companies such as credit card firms. The findings of the research are very complementary with the China case study on the importance of having information and feedback mechanisms. Given APEC’s desire to look beyond GDP as a measure of performance, the exigencies of the Covid-19 as well as its focus on the digital economy, the Digital Economy Steering Group, in cooperation with the Economic Committee, might seek to examine these developments in the economics research literature.

Opportunity for More Inclusive Education with Digital Technology

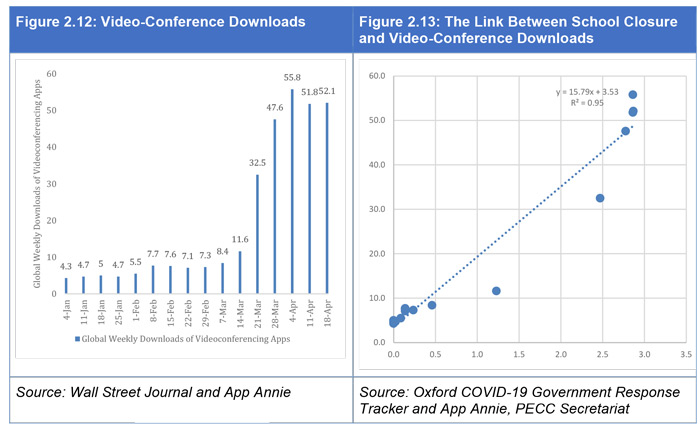

The digital economy has not just been a lifeline for businesses during the great lockdown. It has allowed millions of school children and university students to continue with their education. Figure 2.12 presents data similar to that in Figure 2.10 but limited to video-conferencing apps such as Teams and Zoom. From a base of around 4.5 million weekly downloads in January, this leaps to 50 million in April. Figure 2.13 shows the correlation between the downloads of video-conferencing apps and school closures around the world.

As in the case of workplace closures a similar story is shown, as schools closed more people downloaded video-conferencing apps. There were of course many other things happening at the same time – including office closures that also use video-conferencing apps. If data were available for purely educational apps downloads a similar story would likely arise, as there is plenty of anecdotal evidence. For example, Microsoft has partnered with the Ministry of Higher Education in Thailand to provide Teams for 150 Universities in Thailand, covering over 60,000 educators and over 2 million students.

It is not only in business and education that digital has been a lifeline, but also in medicine. With people unable or frightened during lockdowns to easily visit doctors there has been a risk of other sicknesses going untreated. As a result, some telemedicine providers have reported massive increase in demand for their services.

However, barriers remain to the development of digital delivery in these vital sectors such as finance, education, health care and education including

- Lack of high broadband access

- Restrictions on online payment systems

- Lack of digital ID systems

- Overall restrictive services policies

While APEC has work programs that cover these issues with the APEC Services Competitiveness Roadmap and the APEC Internet and Digital Economy Roadmap, this crisis has laid bare significant gaps in soft and hard infrastructure. Trade and investment flows, supported by cooperation on policy change, could play a significant role in addressing these gaps.

In another example of COVID’s accelerating effect with respect to the application of digital technology, tourist attractions are providing virtual tours during lockdown, often free of charge but requesting voluntary contributions.44 While not able to compensate for the lost revenue due to the lack of visitors, such measures provide some revenue and publicize attractions to new audiences that may generate real visitors in better times.

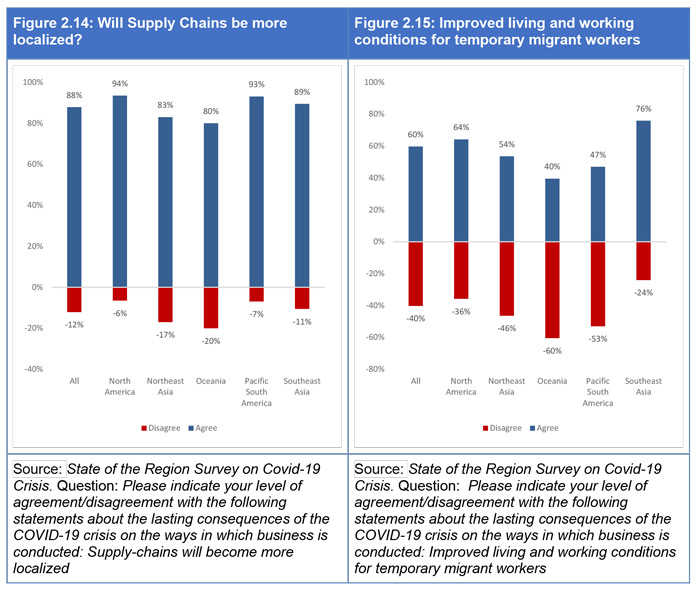

Will Supply Chains be More Localized?

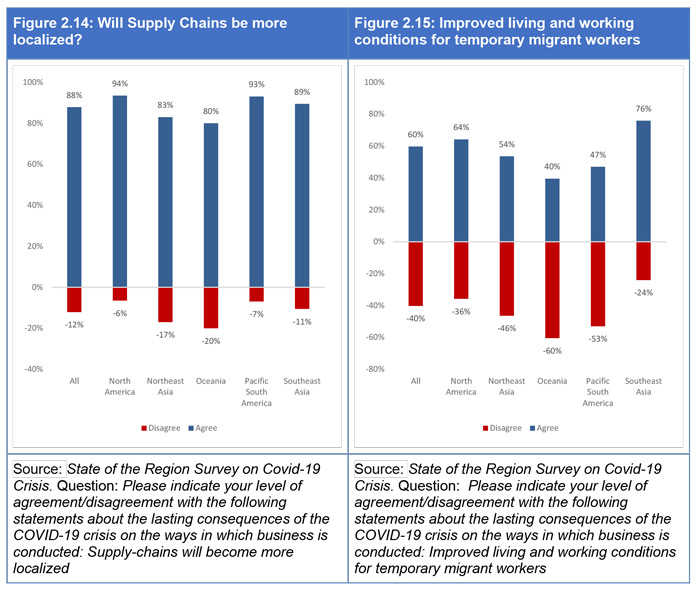

As seen in Figure 2.14, there was a broad perception across the Asia-Pacific that supply chains will become more localized. However, the extent of this sentiment varies between regions, and is relatively low in Oceania. Expectations of the future of supply chains may have been mixed up with issues connected with the broader range of imported goods and the availability of medical/emergency supplies.

Supply chain expert Hau Lee once said

“top-performing supply chains possess three very different qualities. First, great supply chains are agile. They react speedily to sudden changes in demand or supply. Second, they adapt over time as market structures and strategies evolve. Third, they align the interests of all the firms in the supply network so that companies optimize the chain’s performance when they maximize their interests. Only supply chains that are agile, adaptable, and aligned provide companies with sustainable competitive advantage.

With some prescience he goes on to explain that

“While the threat from natural disasters, terrorism, wars, epidemics, and computer viruses has intensified in recent years, partly because supply lines now traverse the globe, my research shows that most supply chains are incapable of coping with emergencies. Only three years have passed since 9/11, but U.S. companies have all but forgotten the importance of drawing up contingency plans for times of crisis.”

There are counter-views to those that supply chains will become more localized. First, there is a lot to lose, since the supply chain architecture has provided gains for participating firms: Japanese firms for example are said to believe that that returning home is impractical and uneconomical.46 A banking analyst is quoted as saying that the costs of reconfiguring some supply are ‘too great’.47 At the economy level, supply chains have delivered productivity growth, higher wages than otherwise, FDI flows, technology transfer and positive spillovers to other local firms. Fragmentation and complexity are the travelling companions of these benefits. Second, while the chain structure involves risks, on which the debate is now focused, the question is how best to manage them.

Miroudot48 discusses the notions of resilience and robustness in supply chains. The former refers to the ability to recover from and the latter to the ability to continue operating during a crisis. Firms make choices with respect to these dimensions and their strategies differ as a result.

A focus on robustness (which is relevant for medical supplies in a pandemic) would lead to diversification of suppliers: self-sufficiency is not recommended because disasters also occur at home. Miroudot argues there is also value in anticipating disruptions (through transparency of the supply chain, and data on capacity and stocks at different points) and in promoting agility. Miroudot also refers to several examples where supply chains across borders were critical in supporting the delivery of medical products, in other words, those chains proved to be robust. We noted earlier the role of flexible industrial systems in contributing to robustness.

However, since it would be costly to be fully prepared for and to maintain a robust network in a global crisis, Miroudot observes in other cases lack of robustness is accepted as a risk and the focus is on resilience. The latter may be supported by fewer suppliers and a long-term relationship with each. Other contributors to resilience are product design (products using more standard inputs) and monitoring and assessment of risks at each point in the chain. The resilience of production networks against supply/demand shocks has been well established in the empirical literature; these structures respond faster once the shock is past.

Better Living Conditions for Migrant Workers

The Covid-19 crisis has also shone a light on the living conditions of migrant workers across the AsiaPacific. For example, in Canada, reports suggest a relatively high proportion of cases among farming communities where migrants work. Ontario Premier Doug Ford when asked if the province would consider increasing inspections and changing laws regarding communal living in cramped bunk houses, said

"that's something we can put on the table. I've been there and seen the congregate living on these farms. Can we do it a month or so? I just don't think that's a reality," said Ford.

Singapore has also faced an outbreak of Covid-19 amongst the migrant worker population. The government of Singapore recently announced plans to improve the quality of housing. As shown in Figure 2.15, given these experiences it probably not surprising that amongst sub-regions it was North America and Southeast Asia that had the highest level of agreement with the statement that the crisis would lead to “Improved living and working conditions for temporary migrant workers”. Interestingly respondents from Oceania were the only sub-region that disagreed with the statement.

Connectivity: Jobs and Trade

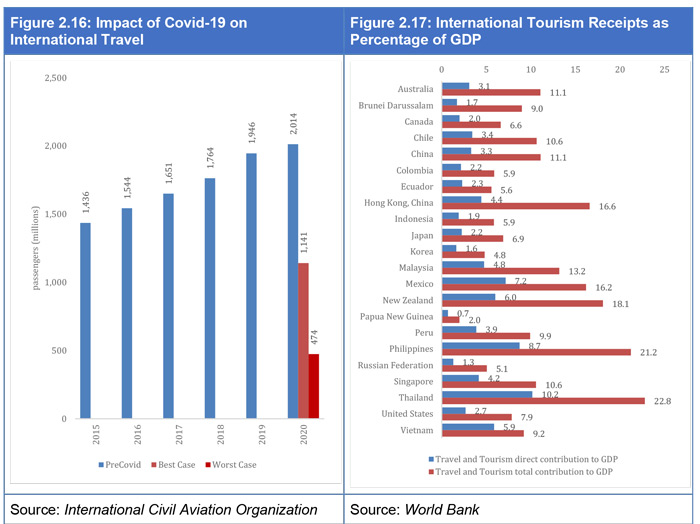

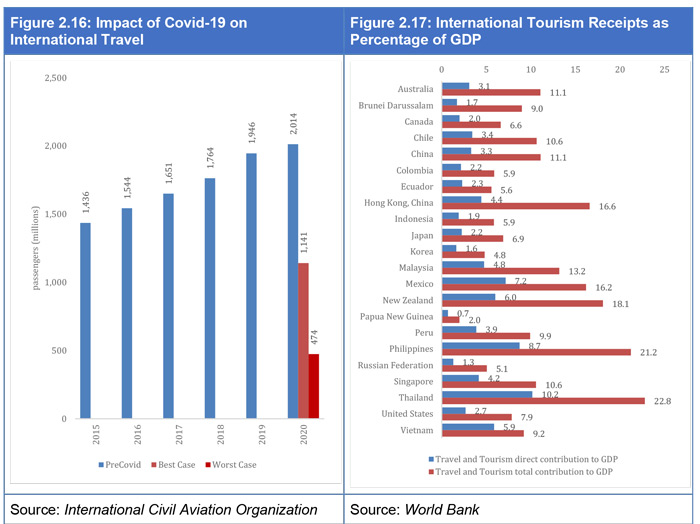

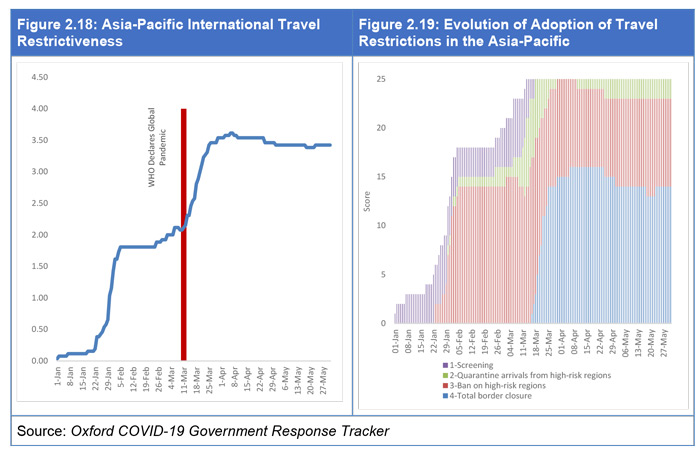

Unlike the Global Financial Crisis, this crisis has been characterized by an almost complete shut down in international travel. The sharp fall in international travel will have a drastic impact on economies in the region. Tourism receipts accounted for around US$721 billion in the Asia-Pacific, while the travel and tourism sector’s direct contribution to GDP in the region ranges from around 2-10 percent (see Figure 2.17). The real issue lies however in the contribution that the sector makes to employment. While travel and tourism directly employ 2 to 7 percent of the labor force, the sector indirectly supports more than 20 percent in Thailand and the Philippines51. Most of these employers are micro, small and medium sized enterprises (MSMEs) with fewer than 50 employees, while a third are micro enterprises employing fewer than 10 people.

Over the past 10 years the number of international passengers has been growing at an average rate of around 7.5 percent a year, well above the growth of the region’s aggregate demand. The estimated number of international passengers in 2019 was around 1.9 billion and had been expected to surpass the 2 billion mark this year. Now scenarios published by the International Civil Aviation Organization paint a grim picture for the year with a best-case scenario of around 1.141 billion passengers this year and a worst case of around 473.9 million (see Figure 2.16).

There are also likely to be large consequences for trade, especially for micro and small and medium enterprises. Case studies suggests that even with the proliferation of ecommerce trading platforms as many 60 percent of MSMEs continue to travel to source products. The gains that ‘travelers’ have created are significant – those firms who import without traveling are 2.5 months behind the frontier available in the source economy and pay a 12 percent premium. 53 With the onset of the Covid-19 traders are no longer able to travel, severely restricting their ability to source new inventory. A significant reason for traders to travel is not only to benefit from lower prices but also to gauge trustworthiness of suppliers. Policy prescriptions in the immediate term include removing restrictions which add to the costs of air travel: this is part of the roadmap strategy for reform in the services sector. Longer term proposals are those for ‘improving contract enforceability’ and ‘improving legal systems’ which are structural reform goals.

APEC does however have an initiative that could help in this area. In 2019, APEC established a Collaborative Framework for Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) of Cross-Border Business-to-Business Disputes. The ODR Framework creates a framework for business, (in particular MSMEs in participating economies) to provide technology-assisted dispute resolution through negotiation, mediation, and arbitration for business-to-business claims. Under this ODR Framework, a business may file a cross-border complaint online against a business in another participating economy in cases where both businesses have consented to have such disputes resolved under the ODR framework.

During the first phase of the procedure, the businesses are allowed to exchange information and proposals, and negotiate a binding settlement of their dispute, through electronic means (“Negotiation Stage”). If the parties cannot reach a binding agreement by amicable negotiations, the relevant ODR provider will appoint a qualified online dispute resolution (ODR) neutral to mediate the dispute (and if possible, reach a binding settlement agreement) (“Mediation Stage”) or to arbitrate the dispute (and issue a binding award) (“Arbitration Stage”). The use of artificial intelligence or other modern technology is encouraged in any of the three stages.

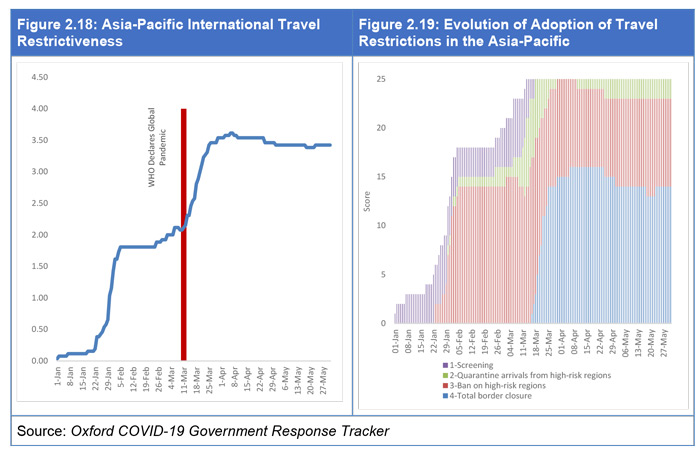

As seen in Figure 2.18, the overall level of international travel restrictiveness in the region has evolved over 3 stages

- Stage 1: approximately coinciding with the month of January when the average level of restrictiveness for the region climbed to 1.8

- Stage 2: from the beginning of February to the beginning of March the level was steady at 1.8 and then began to climb again at the beginning of March and sharply so after the declaration of a Global Pandemic by the World Health Organization

- Stage 3: a steady period where the overall average level of restrictiveness has been above 3.4 since the end of March, which value lies between a ban on high risk regions and total border closure.

Figure 2.19 provides a more detailed breakdown of the evolution of travel restrictions adopted by AsiaPacific economies over the course of the crisis. This more detailed analysis shows how the policy emphasis has shifted over time:

- Screening

- Screening + Ban

- Screening + Ban + Quarantine

- Screening + Ban + Quarantine + Closure

In order to assist the travel and tourism industry, economies have been developing special schemes such as generating alternative revenue; minimizing revenue loss; planning and communication; informing the industry; reducing tax burdens; providing direct financial support; and temporary job reassignment.54 However, these policies run risks of cementing existing structures, sustaining businesses that would not otherwise survive (referred to as the problem of zombie firms), and inhibiting innovation. A more efficient policy response is directed at the source of the problem, which is the lack of confidence in travel once economies re-open.

Rebuilding Confidence in Travel: Bubbles and Fast Lanes

A critical part of the transition to the post-crisis period will be rebuilding confidence in international travel once travel restrictions are formally lifted. Already, major aircraft manufacturers have begun studying how the virus behaves during air travel.

Various bilateral or plurilateral projects are underway. The Fast Lane for business travelers between Singapore and China is providing one example that the world can study 56 while the similar case of the fast track between China and Korea is another.57 The planned Trans-Tasman Covid-safe travel zone between Australia and New Zealand or the Trans-Tasman Bubble 58 will provide the world with a full scale case study in opening up travel between two jurisdictions. Indeed, one consideration that has already been raised is about how the ‘bubble’ might be extended to neighboring Pacific islands. This is critical for many Pacific island economies for whom tourism often accounts for very large percentages of GDP. The Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum, Dame Meg Taylor told an Asia Society Policy Institute event that while several Pacific Island economies had approached New Zealand and Australia about being included in the bubble, the first priority “is that people stay healthy.”59 Japan has announced that it has begun talks with Vietnam, Thailand, Australia and New Zealand to ease visitor restrictions. News reports suggest that visitors will be subject to taking a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for possible coronavirus infection immediately before departure and after arrival and submit schedules of their activities and record their movements using a smartphone app.

While these efforts are welcome, there is value in establishing connectivity between them. Given the international nature of travel, this is an issue most effectively addressed cooperatively and in partnership between consumers, government, and business.

The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) has developed protocols for:

- Hospitality

- Outdoor Retail

- Aviation

- Airports

- Cruise

- Tour Operators

- Convention Centres, Meeting and Events

Common to all of the protocols developed by the WTTC are the objectives:

- Have the private sector lead the definition of industry best practices as Travel & Tourism moves from crisis management to recovery; and

- Put the safety, health and security of travelers and the Travel & Tourism workforce at the core of the development of global protocols.

As well as the approach:

- Ensure coherence through a coordinated, collaborative, and transparent approach, supported by medical evidence, within the Travel & Tourism sector as well as with governments and public health authorities.

- Share harmonized and consistent protocols which are outcome driven, simple and practical across destinations and economies

- Rebuild trust and confidence with travelers through effective communication & marketing; letting them know the protocols implemented and assurances available to keep them safe.

- Advocate for the implementation of enabling policies to support the recovery and demand regeneration for the sector.

Moreover, given the Pacific Island Forum’ observer status in APEC, a technical discussion on the design and application of these protocols would be a valuable opportunity to engage with its members on an issue of almost existential importance to some economies. A technical dialogue could be opened among the agencies implementing the various initiatives to understand how they work and what will be needed as other economies begin to open up. The value of this being with APEC is that it includes major tourist markets.

Relaxing constraints on passenger movements has an important contribution to trade costs. Half of air cargo capacity is in the belly of air passenger flights 61. With the withdrawal of this capacity in the first few months of the year, prices for air cargo were pushed higher. Alexandre de Juniac, IATA’s Director General and CEO said

“At present, we don’t have enough capacity to meet the remaining demand for air cargo. Volumes fell by over 15% in March compared to the previous year. But capacity plummeted by almost 23%. The gap must be addressed quickly because vital supplies must get to where they are needed most. For example, there is a doubling of demand for pharmaceutical shipments that are critical to this crisis. With most of the passenger fleet sitting idle, airlines are doing their best to meet demand by adding freighter services, including adapting passenger aircraft to all-cargo activity. But mounting these special operations continues to face bureaucratic hurdles. Governments must cut the red tape needed to approve special flights and ensure safe and efficient facilitation of crew,”

“The capacity crunch will, unfortunately, be a temporary problem. The recession will likely hit air cargo at least as severely as it does the rest of the economy. To keep the supply chain moving to meet what demand might exist, airlines must be financially viable. The need for financial relief for airlines by whatever means possible remains urgent.”

The statement by de Juniac leads to the issues of state aid for airlines and of competition policy.

State Support for Air Transport

While IATA understandably calls for support, the extent of assistance provided by governments to the airline sector during the crisis is an issue. While regional airlines such as Virgin Australia, Thai Airways, LATAM, Aeromexico, and Avianca filed for bankruptcy63, other airlines have thus far been able to survive the crisis. The extent of government support is not always clear, according to media reports. For example, American Airlines secured $5.8 billion for payroll support, United Airlines expects to get $5 billion in grants and low-interest loans, and has applied to borrow up to $4.5 billion from the U.S. Treasury. On the European side, Lufthansa received 9 billion Euro64, and Air France-KLM 11 billion Euro.

IATA reports (as of the end of May) that there has been little government support for airlines in emerging economies, especially in East Asia: higher levels of support are observed in developed economies. Support also varies between developed economies: compared to airline revenue in 2019, it is relatively high in the US, Japan, and Singapore. In another example of the risks of support for particular firms, IATA observes there is little correlation between support and the viability of the business model of the airline based on recent performance. IATA also notes that the bulk of support provided (55%) will have the effect of adding to debt rather than providing equity (which accounted for 11% of support: the balance of 34% is based on subsidies).

Greater weight on self-reliance leads to greater use of subsidies and other forms of support. An alternative is to take a value chain approach to this sector, and consider ways in which the service can be provided by access to the capacity offshore providers, and impediments to that result. The cross-border delivery of air transport services is, according to data from the OECD, relatively highly restricted.65 A reform agenda, especially with respect to rules on foreign investment is valuable in this context. ASEAN has made air transport a priority area for its own economic integration and that effort could be expanded to the APEC region, through the work on the Services Competitiveness Roadmap.

The participation of government in the air transport is but one example of assistance at the sectoral level. This has been broad based, and potentially very distorting. Is this likely to continue? This is the topic of the next section.

The Role of Government in the Post-Crisis Era

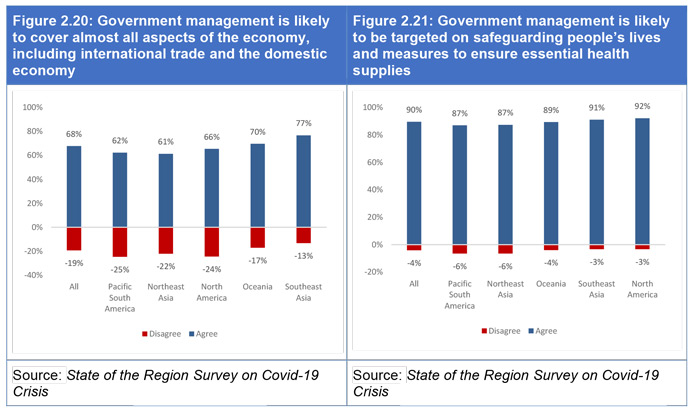

To develop a baseline of the regional policy community’s views on these issues, respondents were asked to give their level of agreement on two statements:

- Government management is likely to cover almost all aspects of the economy, including international trade and the domestic economy

- Government management is likely to be targeted on safeguarding people’s lives and measures to ensure essential health supplies

Figures 2.20 and 2.21 break down the responses to these questions at the sub-regional level. Many respondents expect government intervention to continue to be widespread. At the same time, there is an expectation that these interventions will be more tightly targeted.

A more important structural reform issue following the COVID experience will be how to extract governments from their crisis roles that emerged during the pandemic and in the course of exit strategies. There are two aspects, one related to support and the other to regulatory reform.

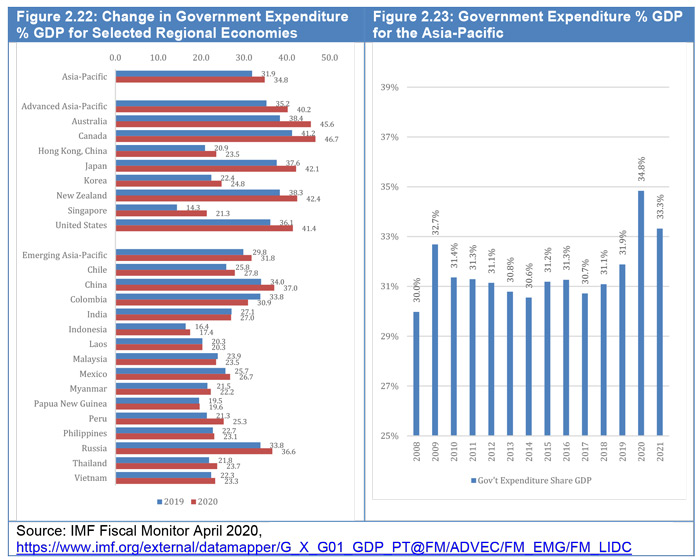

Figure 2.22 above shows the expected change in government expenditure as a percentage of GDP between 2019 and 2020 for those Asia-Pacific for whom data was available. As seen in the chart, the change for region as a whole is an increase of 3 percentage points. But for many, especially the region’s advanced economies, the size of government will increase by considerably more, as much as 7 percentage points, according to data from the IMF.

Figure 2.23 shows the size of government expenditure as a percentage of GDP for the same group of AsiaPacific economies since 2008. Following the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, the government expenditure as a percentage of GDP increased from 30 percent of GDP to 32.7 percent but over time as economies recovered it decreased back towards pre-GFC levels.

As already noted, the persistence of current policies of support, for instance, has not only significant fiscal consequences but also implications for efficiency and for productivity. Movement back from that support will most likely meet resistance, from the new sets of interests that have been created, in particular. Others may argue that in the context of the uncertainty created by the pandemic, it is unwise to unravel the emergency arrangements prematurely. A framework for responding to the pressures of those interest groups and those arguments will be valuable One well-tried option is that of the public policy framework, which is based on a series of questions related to the nature of the problem to be solved, the tools available to do so, the scope to use market mechanisms rather than regulation followed by a ranking of options and selection of a preferred response. The design of processes for and institutions for managing this work is an important element of regional cooperation, which is the topic of the next section.

The second element is regulatory reform. In this respect, recent experience has included instances of regulatory retreat by governments different from the subsidy elements. Many rules and regulations have been relaxed to lower business costs and facilitate new ways of operating that are consistent with the response to the pandemic. The WTO recently documented such measures as applied in the services sector.66 Examples include changes in the regulation of medical services to facilitate the use of telehealth. The information provided by these experiments in reform should be evaluated as to whether each has value that should be continued in the post-crisis environment. There is also value in sharing these results and cooperation on capacity building for the management of reform.