Chapter 2 - OPINION LEADERS’ SURVEY*

*Eduardo Pedrosa is Secretary General of Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC).

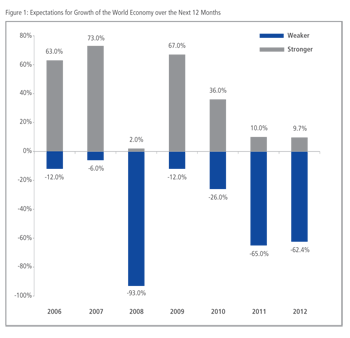

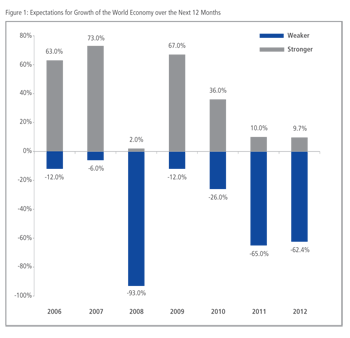

A sense of economic gloom continues to  pervade the Asia-Pacific. Sixty-two percent of respondents to our annual survey expect the growth of the world economy to be somewhat weaker to much weaker over the next 12 months. This level of pessimism is similar to sentiments in last year’s survey which indicates a perception that the recovery that started in 2010 is stalling (See Figure 1).

pervade the Asia-Pacific. Sixty-two percent of respondents to our annual survey expect the growth of the world economy to be somewhat weaker to much weaker over the next 12 months. This level of pessimism is similar to sentiments in last year’s survey which indicates a perception that the recovery that started in 2010 is stalling (See Figure 1).

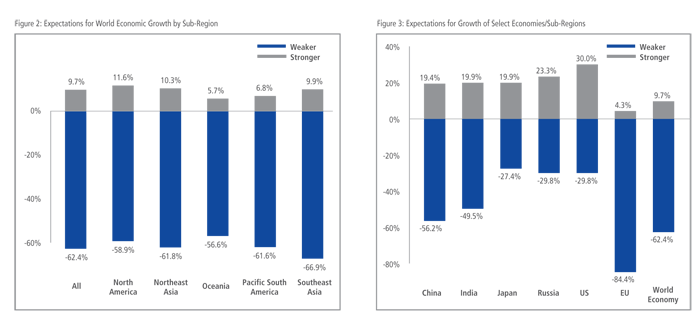

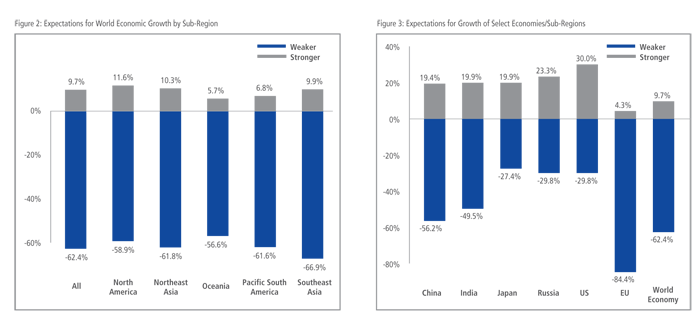

The negative sentiments about the global economy are fairly evenly spread across the Asia-Pacific, but are currently strongest in Southeast Asia. Slightly more than two thirds of respondents from Southeast Asia expect the word economy to be weaker over the next 12 months and (See Figure 2). North American respondents were a little less pessimistic than those from other sub-regions.

Growing Pessimism on Emerging Markets

While views on the global outlook are essentially unchanged from last year, views on emerging markets have turned from being equivocal to negative. In last year’s survey although the negative impulse was already evident with 36 percent of respondents expecting weaker growth in China compared to 30 percent expecting stronger growth, this year 56 percent of opinion leaders are gearing themselves for weaker economic performance from China over the next 12 months.

Views on India, which was the only economy where the balance of opinion was towards stronger growth last year, have also gone negative with 49 percent of respondents expecting weaker growth over the next 12 months.

Views on the US economy have turned marginally positive. Whereas views on the US in last year’s survey showed 80 percent expecting weaker growth, this year’s views are evenly split with 30 percent expecting stronger growth and 30 percent weaker with the balance expecting growth to remain at the same level as the previous 12 months.

Views on Japan’s economic growth, while still in negative territory are also showing some improvement. Last year, 57 percent expected weaker growth from the region’s third largest economy. This year, the number has more than halved to 27 percent. Indeed, 53 percent of respondents expect Japan’s economic performance to be ‘about the same’ over the next year as it has been for the last 12 months.

Opinion leaders are split on the prospects for growth in Russia, this year’s APEC host. Some 30 percent of respondents expect growth to be weaker over the next 12 months, while 23 percent expect it to be stronger.

Unsurprisingly, views on the prospects for growth in the EU are overwhelmingly negative with 84 percent expecting weaker growth and just 4 percent expecting stronger growth.

These views are somewhat in contrast to prevailing forecasts for the European Union which indicate a mild recession in 2012 and a slight rebound in 2013.

Opportunities for Growth

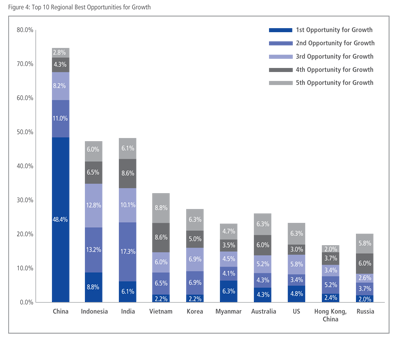

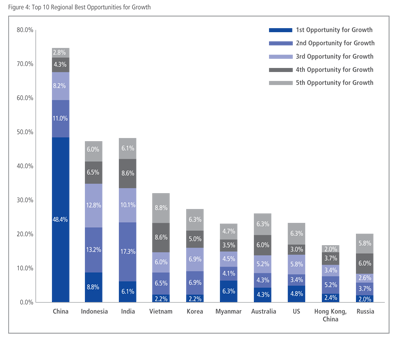

Even though opinion leaders are concerned about short-term prospects for growth in emerging markets, over the next 5 years, they see growth coming from the major emerging markets in the region; especially China, Indonesia and India (See Figure 4). China, by far outweighs all other markets as an opportunity for growth. While close to 50 percent of respondents picked China as the top opportunity for growth, Indonesia, while second in the list, had close to 9 percent of respondents ranking it as the top opportunity for growth.

In spite of the current economic outlook  and emphasis on emerging markets as drivers of growth, regional opinion leaders picked two developed market economies, Australia and the United States as top 10 opportunities for growth. Interestingly, Northeast Asians were the most bullish on the US economy while Southeast Asians were the least. Perhaps even more telling is that business respondents were more positive about the US as a growth opportunity than either government or non-government panelists.

and emphasis on emerging markets as drivers of growth, regional opinion leaders picked two developed market economies, Australia and the United States as top 10 opportunities for growth. Interestingly, Northeast Asians were the most bullish on the US economy while Southeast Asians were the least. Perhaps even more telling is that business respondents were more positive about the US as a growth opportunity than either government or non-government panelists.

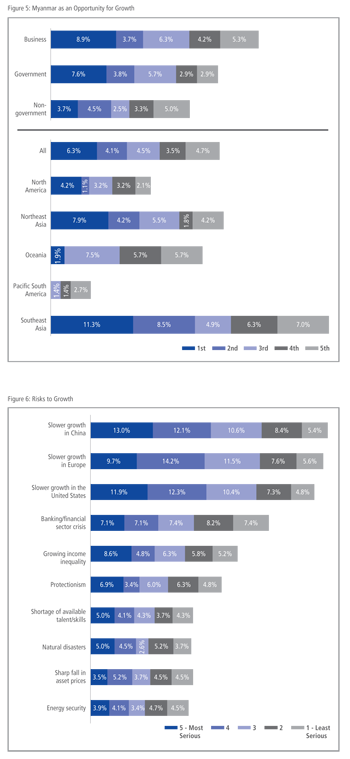

Myanmar

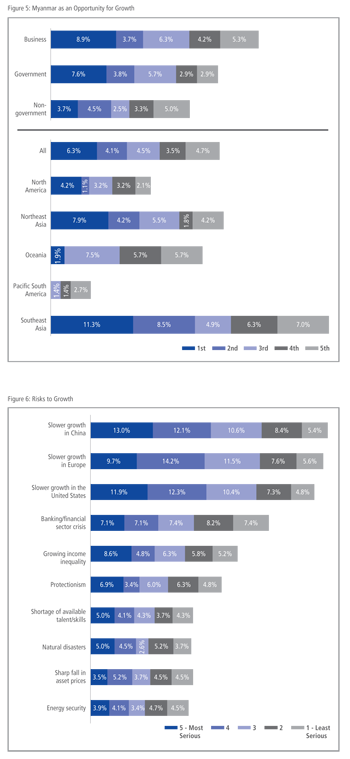

Although not part of PECC or APEC and barely  integrated into the broader Asia-Pacific economy, Myanmar was ranked as the 6th best opportunity for growth. Some 23 percent of respondents selected Myanmar as a top 5 opportunity for growth. However, there were very wide variations of views. Those most interested in Myanmar were respondents from Southeast Asia; in other words, fellow ASEAN members. Respondents from South America were significantly less interested in Myanmar than other sub-regions in the Asia-Pacific. Business respondents were much more interested in Myanmar than those from the government or the non-government sectors.

integrated into the broader Asia-Pacific economy, Myanmar was ranked as the 6th best opportunity for growth. Some 23 percent of respondents selected Myanmar as a top 5 opportunity for growth. However, there were very wide variations of views. Those most interested in Myanmar were respondents from Southeast Asia; in other words, fellow ASEAN members. Respondents from South America were significantly less interested in Myanmar than other sub-regions in the Asia-Pacific. Business respondents were much more interested in Myanmar than those from the government or the non-government sectors.

Risks to Growth

Slower Growth in China Biggest Risk to Growth

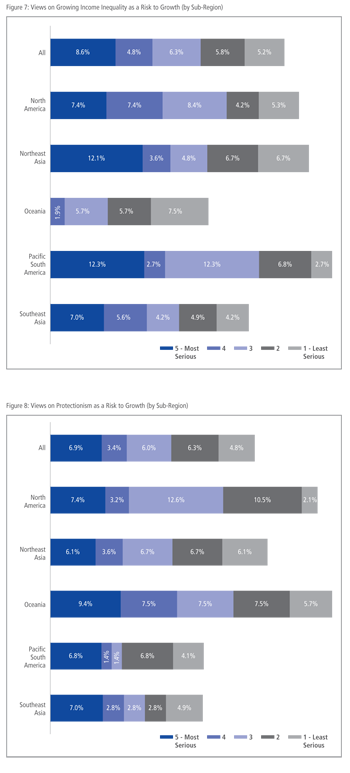

Big macroeconomic factors continue to dominate concerns about growth. Close to half of all respondents picked slower growth in China, Europe and the United States as top-five risks to growth for their own economy. Interestingly, slower growth in China was of marginally higher concern than a slowdown in either Europe or the US. This somewhat affirms views expressed on the outlook for growth in China above.

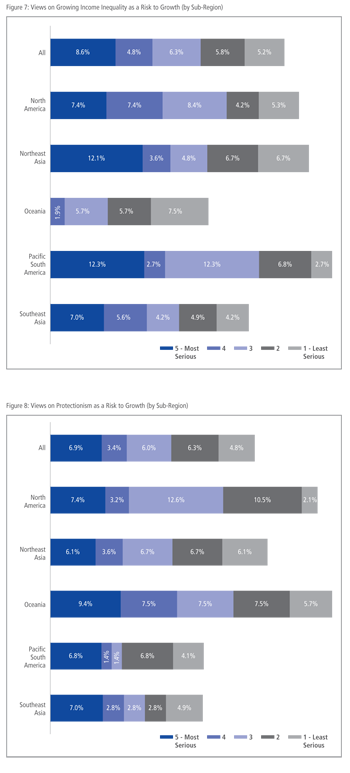

What should be of concern to regional policy-makers are  views on protectionism and income inequality as risks to growth. Income inequality was already concern before the economic crisis struck but has been exacerbated by the crisis.

views on protectionism and income inequality as risks to growth. Income inequality was already concern before the economic crisis struck but has been exacerbated by the crisis.

Concerns over income inequality were expressed the highest risk by respondents from South America with 37 percent of respondents selecting income inequality as a risk to growth, followed by Northeast Asia (34 percent) and North America (33 percent) and least by those from Oceania. The APEC Growth Strategy emphasized the need for inclusive growth. However, views from opinion leaders indicate that this is an area where further work should be done.

On protectionism, respondents from Oceania were most concerned with 38 percent selecting it as a top 5 risk to growth for their economy, followed by North Americans at 36 percent. While resisting protectionism was highlighted at the peak of the crisis, evidence suggests that it has been increasing and covering a growing percentage of global trade. The risk is that as the recovery stalls, as opinion leaders seem to fear, that protectionism will simply continue to increase. As PECC Statement to APEC Trade Ministers warned last June, the number of trade restrictiveness practices adopted by regional economies was at 431 – or 20 percent of all trade restrictive measures implemented across the world since the start of the crisis. These measures come despite the calls of our leaders for a standstill on the adoption of protectionist policies

Box 2-1: Myanmar: Are the reforms for real?^

Myanmar was ranked as the 6th best opportunity for growth, even though it is neither a PECC nor APEC member. Business respondents were much more interested in Myanmar than those from the government or the nongovernment sectors.

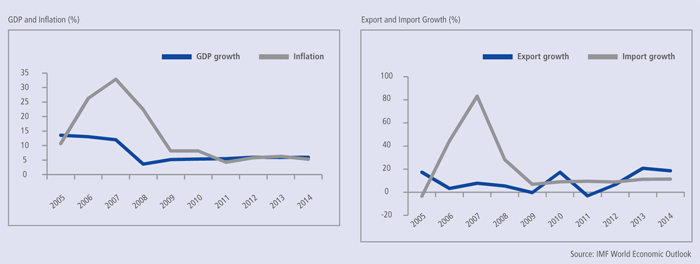

One reason for this is that the winds of change are picking up in Myanmar. Since his inauguration on 30 March 2011, President Thein Sein has initiated several steps that reflect a new approach to governance. His inaugural address highlighted transparency, accountability, good governance, rule of law, as well as the need to deal with corruption, cronyism and widening gap between the rich and poor.

In light of the reforms taking place in Myanmar, the international community has begun taking steps to ease sanctions imposed on the economy. On 16 May 2012, the European Union officially suspended all sanctions against Myanmar until 30 April 2013, with the exception of the arms embargo. The United States also announced the easing of financial and investment sanctions on 17 May 2012, and subsequently implemented those measures on 11 July 2012.

The spotlight is very much on Myanmar, and the focus will only increase in the next two years as Myanmar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and chairs the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. There is now a unique opportunity to change the trajectory of growth and uplift the lives of its citizens.

Will the reforms last?

Myanmar is now experiencing vast change and transformation. But what has surprised observers more than the reforms has been the exhilarating pace at which they have been carried out. Inevitably, this has led observers to cast doubt on the sustainability of the reforms.

Whether the reforms are irreversible depend on what factors motivated the change.

While the reform process could flounder if there is strong opposition to it by those who would prefer the status quo, the possibility that the government would be forced to back track is slim. The principal reason is that most of the impetus for change comes from within. Due to the ascendancy of science and technology and the increasing use of the internet and mobile phones, the people are connected like never before and are aware of the vast changes that are taking place in the world. They desire real change. The military too has a new generation of leaders that are aware of the aspirations of the people.

Geopolitics is another compelling factor that is driving the reforms. Myanmar may be small and undeveloped but is one that is strategically located, wedged as it is between China and India, the two fastest growing economies in the world. When Western sanctions were in place, neighboring economies were well-placed to fill the vacuum. Myanmar had few markets to enter and China, India, Thailand and other ASEAN members had no competition in entering the market. As of 2010, over 70 percent of Myanmar’s exports went to just three markets; Thailand, India, and China. In addition to geographical reliance on a few markets, it is also heavily dependent on natural resource exports – oil and gas approximately 40 percent of all exports and gemstones another 25 percent.

The challenges that lie ahead

As Myanmar forges ahead with its reforms, it will have to overcome serious challenges. The most difficult task will be to unite it by finding a lasting solution to the majority-minority tensions that have plagued Myanmar since independence in 1948. The Union of Myanmar is made up of 135 ethnic groups, Estimates are that the Bamar make up close to 70 percent of the population with the balance from others including the Kachin, Kayah, Kayin, Chin, Mon, Rakhine and Shan.

The new government has made a good start by reaching out to the ethnic groups just as it has to the political opposition. All but one group, the Kachin Independence Organization, have signed preliminary peace agreements with the government. There are signs that further progress can be made. But the recent flare-up of tensions between the Rakhine and Rohingya communities serve to underscore the daunting challenge the government faces.

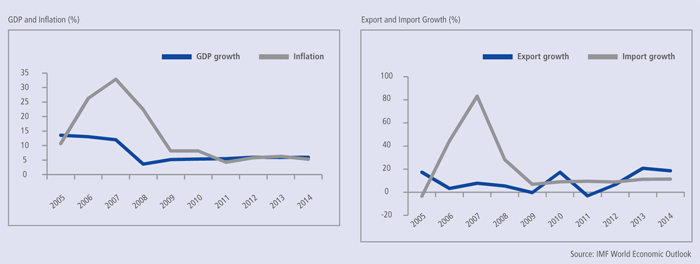

The second challenge for the new government will be to meet the expectations of the people for greater economic opportunities. The International Monetary Fund, following a visit of its mission to Myanmar in January 2012, has published an analysis of the economic situation in Myanmar in which it stresses the need to take further steps to stabilize the economy. The report pointed out the need for structural reforms as well as the need to improve monetary and fiscal management.

One concern that has been the focus of extensive debate in the past year is the exchange rate, as a realistic exchange is sine qua non for the economy to take off. Since 1 April 2012, the Myanmar Central Bank has set a reference exchange rate of 818 kyats to the dollar. Previously, the official rate was 6.4 kyats to the dollar, while the black market rate was 800 to 1000 kyats to the dollar. As a resource rich economy, Myanmar runs the risk of “Dutch Disease” as the reform process unfolds; finding the right policy mix that enables inclusive growth process is an added dimension of to the exchange rate reform. The success of the managed currency float will pave the way to a more open, market-based economy and attract foreign investors. A new foreign investment law is also under consideration in the parliament.

The third challenge would be to develop human resources as there are gnawing gaps in the state’s capacity to implement the reforms to meet the aspirations of the people. . There is limited institutional and technical capacity to carry out detailed policy formulations and to implement some of the changes being adopted. This is acting as a brake on the reform process and means that citizens will not be able to see the full impact of some of the changes. The pressures on the system are only likely to increase in the next two years as Myanmar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. Unless the civil servants and the technocrats have the capacity to deal with the new environment, the economy cannot achieve its goals. As part of the efforts to build this capacity, in 2011 the Myanmar Development Resource Institute (MDRI) was established with three centers: 1) Center for economic and social development; 2) Center for strategic and international studies; and 3) Center for legal affairs.

If the government can overcome these challenges, it will make a large difference to the peoples' lives. While the baseline estimates for growth in Myanmar remain modest with the IMF forecasting an average of 6 percent growth over the next 5 years. However, the Economist Intelligence Unit estimates that if the reform process continues and investments in infrastructure and human resources come in, average growth could be from 7 to 8 percent. While if reforms stall growth would likewise suffer and be at the lower end of 4.5 percent.

In all of this, the government, the opposition in Parliament including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, need to find ways to work together on the reform process. Myanmar has seen more positive changes in the past year than in the half-century proceeding, but still has many challenges to overcome.

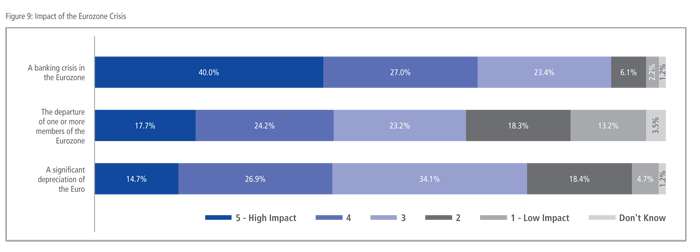

The Eurozone Crisis

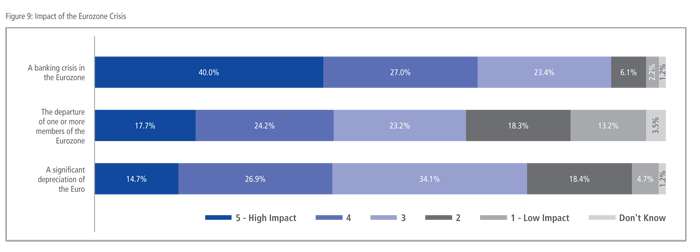

Regional opinion leaders clearly believe that the impact of the Eurozone crisis on the Asia-Pacific is an issue that APEC leaders should discuss in Vladivostok. Of the possible fallouts from the current turmoil, opinion leaders are most concerned about the possible impact of a banking crisis in the Eurozone, followed by a significant depreciation of the Euro and then a departure of a Eurozone member. A large proportion (40 percent) thought that a banking crisis in the Eurozone would have a high impact on their economy compared to under 20 percent who thought that a depreciation of the Euro or a departure of a member of the Eurozone would have.

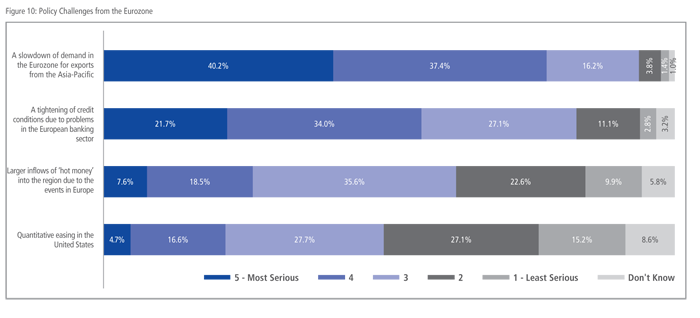

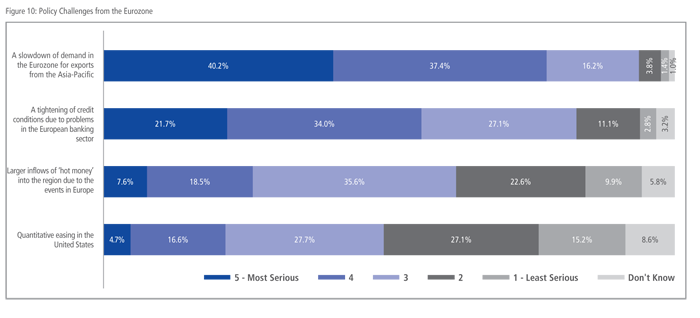

On the policy challenges emanating from the Eurozone, by far the biggest concern is over the likely slowdown of demand from Europe for the region’s exports. More than double the number of respondents selected this as the most serious challenge facing policy-makers than those who selected a tightening of credit conditions – the next most serious issue.

Priorities for Trade Agreements

There are a number of tracks being pursued that could ultimately lead to a Free Trade Agreement of the Asia-Pacific: the Trans- Pacific Partnership and the ASEAN Plus approaches.

Analyses of various templates of trade agreements in the region show that most agreements include tariff reductions, and that there are differences in approaching nontariff barriers. US agreements had higher scores than ASEAN agreements on average and especially in provisions related to competition, intellectual property rights, government procurement, state-owned enterprises, and labor. ASEAN agreements had higher scores than US agreements in a few areas, including dispute resolution and cooperation (See “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: Policy Implications,” by Peter A. Petri and Michael G. Plummer, www.piie.com/publications/pb/pb12-16.pdf).

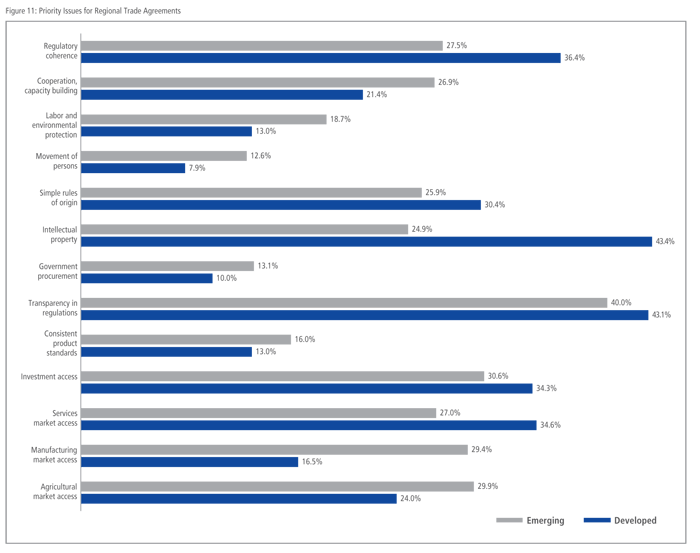

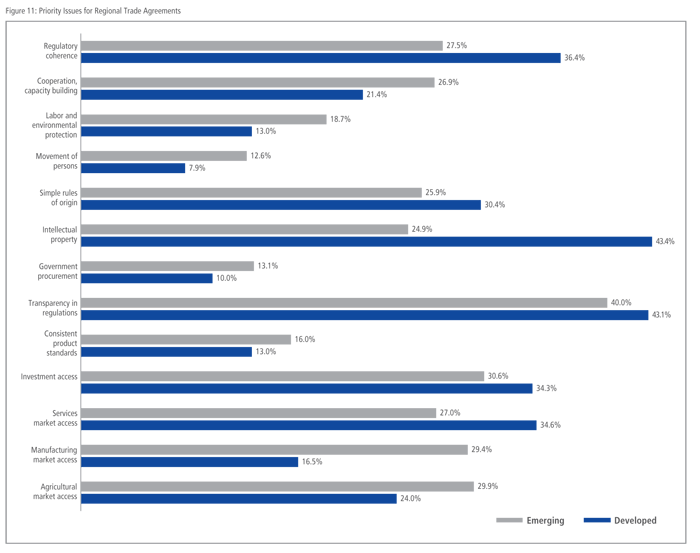

The views of opinion leaders tend to support the view that the different templates reflect the comparative advantages of the different economies. Asian agreements, negotiated largely by emerging economies with comparative advantages in manufacturing, focus on market access for goods while the templates negotiated by the United States reflect the interests of advanced economies by placing emphases on services, investment, and intellectual property.

While there is some divergence in regional views on regulatory coherence, transparency in regulations is an issue that both developed and emerging economies agree on. This indicates some considerable room for useful policy dialogue to bridge gaps in views.

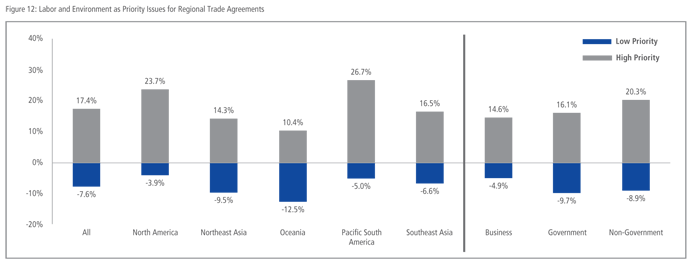

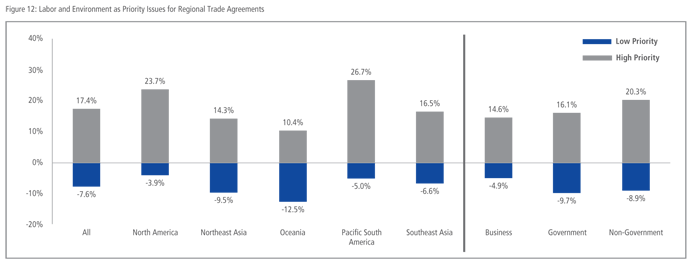

One surprising result from the survey is the level of priority that emerging market opinion leaders place on labor and environmental protection. Close to 19 percent of respondents from emerging market economies rated labor and environment protection as a high priority compared to 13 percent in developed market economies.

Labor and the Environment: Divergence among Emerging Economies

As discussed above, the survey gave a surprising result on the priority that opinion leaders in emerging market economies place on labor and environment protection. This is one set of issues rarely included in the East Asian template but in many agreements involving developed economies, especially the United States, are labor and environment standards. Breaking down the survey results by sub-region and sectors shows where there remain some possible divergences. Respondents from Pacific South America – Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru – all defined as emerging economies in this survey, placed a higher priority on this issue. Respondents from Southeast Asia put much less emphasis on these issues.

Pathways to a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific

At their summit in Yokohama in 2010, APEC Leaders committed to “take concrete steps toward realization of a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP), which is a major instrument to further APEC's regional economic integration agenda. An FTAAP should be pursued as a comprehensive free trade agreement by developing and building on ongoing regional undertakings, such as ASEAN+3, ASEAN+6, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, among others.”

To gauge sentiments around the region on these different pathways, we asked two separate but related questions: which of the trade agreements was likely to succeed and which offers the best pathway to a FTAAP.

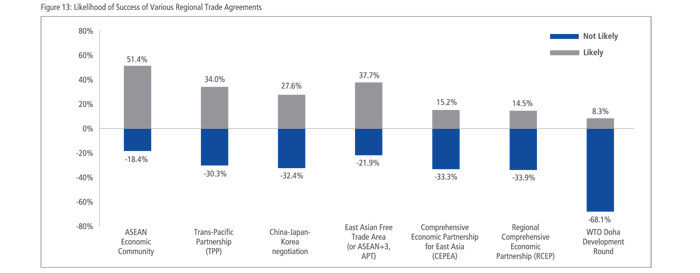

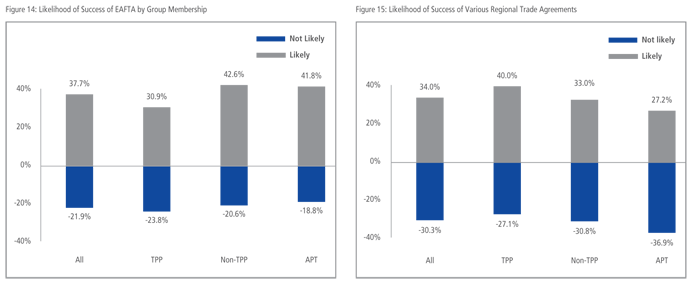

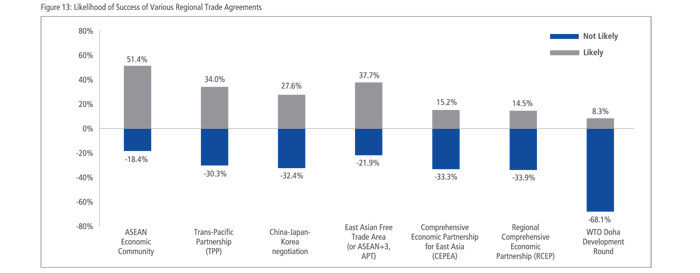

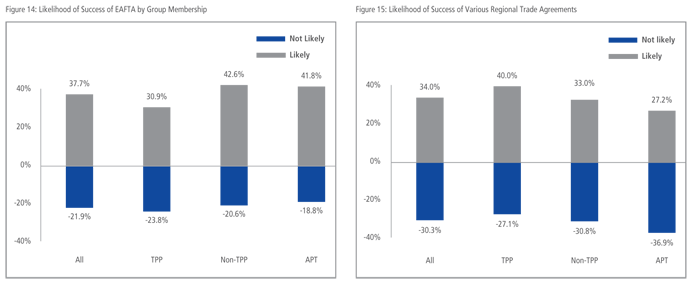

On the whole, opinion leaders were most positive about the success of the ASEAN Economic Community and least about the prospects for the WTO Doha Development Round. There is a great deal of uncertainty about the broader ASEAN Plus track (whether plus 3, plus 6, or plus X – EAFTA, CEPEA and RCEP) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Even though the TPP is well advanced - now into its 13th round of negotiations - only a plurality of respondents thought it was likely to succeed (34 percent); subtracting those respondents who think it is not likely to succeed, there is a net positive of less than 4 percent. While the EAFTA, which is yet to begin formal negotiations, has a slightly larger plurality of close to 38 percent who think it will succeed.

East Asian Free Trade Area (ASEAN Plus 3)

Although the East Asian Free Trade Area (also known as the ASEAN Plus 3) remains an idea, albeit one that has been studied intensively, in general, opinion leaders in the Asia-Pacific think that it has a chance of success, with 38 percent of respondents ranking it as likely to succeed with under 22 percent thinking it not likely. There are some considerable variations in views around the region. Respondents from economies which are negotiating parties to the TPP tend to have a slightly less positive view on the likelihood of success of EAFTA, while potential parties to the agreement are more positive.

The same is true for the TPP. While regional views on the likely success of the TPP negotiations are marginally positive, TPP members (TPP 13) are the most positive about the possibility of its success. However, respondents from economies which are parties EAFTA/APT are in fact pessimistic about the likelihood of the success of the TPP negotiations.

As will be discussed with respect to priorities for the APEC leaders’ meeting, there is considerable disagreement on the WTO DDA. While the overwhelming majority of respondents do not think the WTO DDA round is likely to be successfully concluded, there is considerable variation of views on this issue. As measured by the coefficient of variation (the standard deviation over the mean), while there is a similar variety of views on the regional trade arrangements of around 32 to 37 percent, with respect to the WTO DDA it is a high 52 percent.

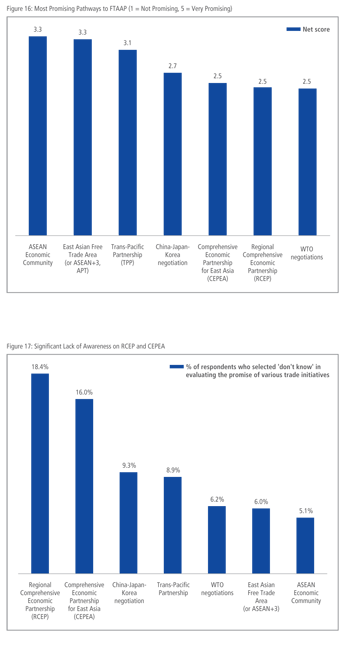

Which Pathway for FTAAP?

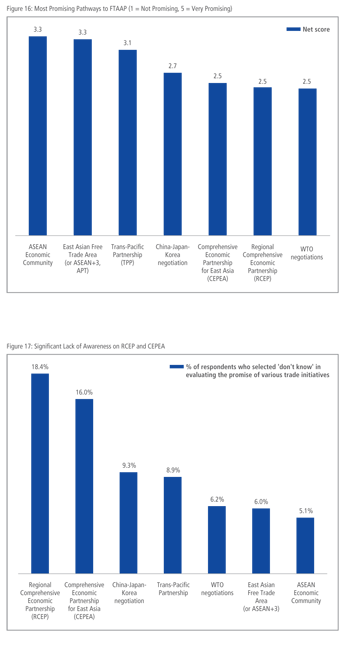

A slightly different variation on the theme of pathways to the question is which putative agreement is the best pathway towards FTAAP. At the regional level, after years of debate there is little to choose between the transpacific track as represented by the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, and the East Asian Free Trade Area (EAFTA, also known as the ASEAN Plus 3, or APT).

The ASEAN Economic Community, which by its nature  is limited to ASEAN members only, is nonetheless considered as the most promising pathway to a free trade area in the Asia-Pacific, followed by the East Asian Free Trade Area and then the Trans- Pacific Partnership agreement. The relatively newer concept of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) launched by ASEAN in November 2011 ranked rather low. However, it may be too early for such a judgment as the details of the mechanics of the RCEP are yet to be decided let alone socialized among the broader community. Close to 20 percent of respondents selected ‘Don’t know” in evaluating RCEP.

is limited to ASEAN members only, is nonetheless considered as the most promising pathway to a free trade area in the Asia-Pacific, followed by the East Asian Free Trade Area and then the Trans- Pacific Partnership agreement. The relatively newer concept of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) launched by ASEAN in November 2011 ranked rather low. However, it may be too early for such a judgment as the details of the mechanics of the RCEP are yet to be decided let alone socialized among the broader community. Close to 20 percent of respondents selected ‘Don’t know” in evaluating RCEP.

The relative lack of awareness about Comprehensive Economic Partnership for East Asia and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership points to a need for a great deal more of dialogue and socialization of these proposed pathways.

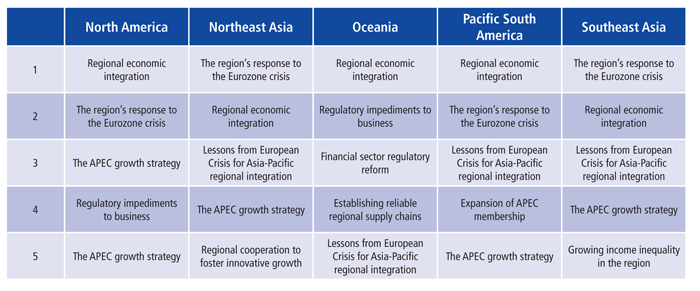

Top Issues for APEC Leaders’ Meeting

The leaders of Asia-Pacific region will gather in Vladivostok confronted with an enormous range of issues. While APEC has a large continuing agenda, inevitably the agenda will become dominated by issues of the day. This year, such meetings have been dominated by concerns and possible policy actions in response to events in the Eurozone.

- Regional economic integration (including the TPP and the ASEAN Plus agreements among others)

- The region’s response to the Eurozone crisis and lessons from the crisis for Asia-Pacific regional integration

- The APEC growth strategy

- Regulatory impediments to business

- Regional cooperation to foster innovative growth

Russia’s Priorities Well Supported by Regional Opinion Leaders

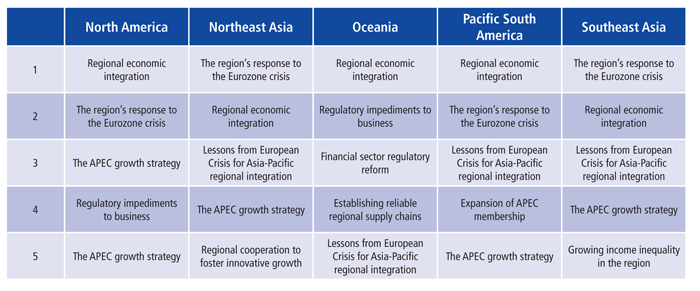

Looking at APEC Leaders’ priorities from the sub-regional level, while there is much common emphasis on issues such as regional economic integration, the response to events in Europe and the APEC growth strategy, some issues are of higher concern to different sub-regions. North America and Oceania, largely composed of developed market economies include addressing regulatory impediments to business as one of top 5 priorities for APEC Leaders’ discussion, while Southeast Asia, mostly emerging economies, puts more emphasis on growing inequality. Only South America, which includes more respondents from non-APEC member economies, places the expansion of APEC membership as a top-5 priority.

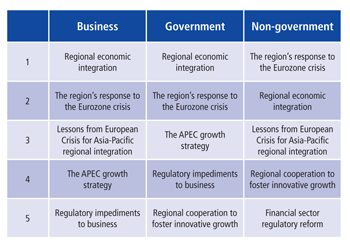

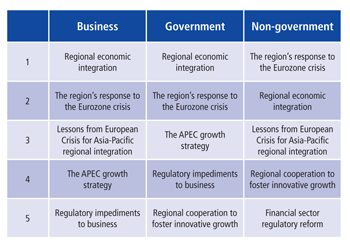

Looking across different segments of society, there  is a good deal of convergence on top priorities for the APEC Leaders’ meeting: non-government respondents, unlike government and business, include financial sector regulatory reform as a top- 5 issue, while government and non-government included regional cooperation to foster innovative growth and respondents from the business sector included regulatory impediments to business in their top-5 list.

is a good deal of convergence on top priorities for the APEC Leaders’ meeting: non-government respondents, unlike government and business, include financial sector regulatory reform as a top- 5 issue, while government and non-government included regional cooperation to foster innovative growth and respondents from the business sector included regulatory impediments to business in their top-5 list.

Region Divided on the Doha Round

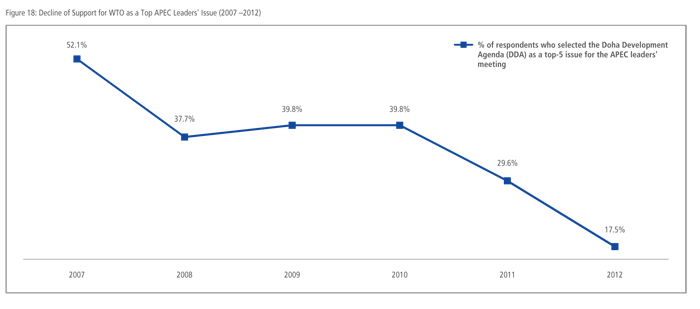

Since 2007, the annual survey of opinion leaders has asked for respondents’ views on the top 5 priorities for APEC summit discussions, and without fail, the WTO Doha Development Round has been a priority, until this year. It is not that other factors have become more important; indeed, while there has been tremendous variation in issues opinion leaders think APEC summits should address ranging from climate change, cutting red tape, reducing corruption, to regulatory coherence, there have been two constant items – regional economic integration and the multilateral system.

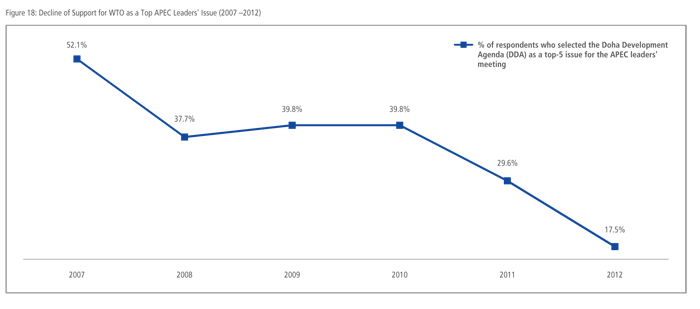

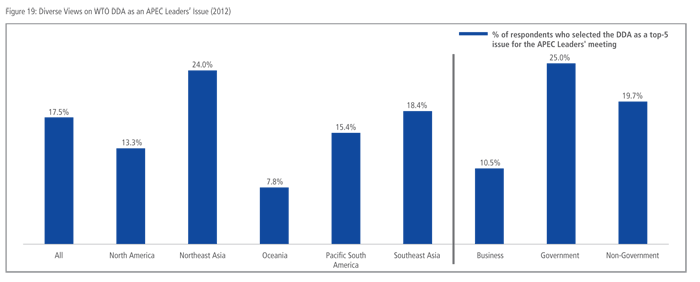

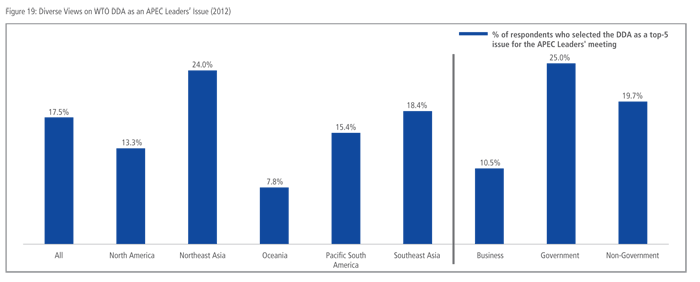

However, while there has been a general decline in interest of discussing the WTO Round at APEC Leaders’ meetings over time (See Figure 18), there are considerable differences in emphasis on this across the Asia-Pacific region. North Americans placed the Doha Development Round 17th (13 percent of respondents listed the WTO DDA as a top-5 priority), Northeast Asia 7th (24 percent), Oceania 21st (8 percent), Pacific South America 17th (15 percent), and Southeast Asia 11th (18 percent) (See Figure 19).

The decline in support for spending time discussing the Doha Development Round is most pronounced amongst the business community. Only 10 percent of business respondents listed the multilateral negotiations as a top-5 issue for APEC Leaders’ discussions – less than half the number of non-government respondents. This finding, while disturbing, should not come of any surprise. For some years the regional business community has been pushing the idea of a free trade area of the Asia-Pacific. Given the differing views among respondents from sub-regions, we may yet see more emphasis on the trade round depending on the host economy.

For detailed results of the survey, please refer to Annex B.

<< Previous

Next >>

pervade the Asia-Pacific. Sixty-two percent of respondents to our annual survey expect the growth of the world economy to be somewhat weaker to much weaker over the next 12 months. This level of pessimism is similar to sentiments in last year’s survey which indicates a perception that the recovery that started in 2010 is stalling (See Figure 1).

pervade the Asia-Pacific. Sixty-two percent of respondents to our annual survey expect the growth of the world economy to be somewhat weaker to much weaker over the next 12 months. This level of pessimism is similar to sentiments in last year’s survey which indicates a perception that the recovery that started in 2010 is stalling (See Figure 1).

and emphasis on emerging markets as drivers of growth, regional opinion leaders picked two developed market economies, Australia and the United States as top 10 opportunities for growth. Interestingly, Northeast Asians were the most bullish on the US economy while Southeast Asians were the least. Perhaps even more telling is that business respondents were more positive about the US as a growth opportunity than either government or non-government panelists.

and emphasis on emerging markets as drivers of growth, regional opinion leaders picked two developed market economies, Australia and the United States as top 10 opportunities for growth. Interestingly, Northeast Asians were the most bullish on the US economy while Southeast Asians were the least. Perhaps even more telling is that business respondents were more positive about the US as a growth opportunity than either government or non-government panelists. integrated into the broader Asia-Pacific economy, Myanmar was ranked as the 6th best opportunity for growth. Some 23 percent of respondents selected Myanmar as a top 5 opportunity for growth. However, there were very wide variations of views. Those most interested in Myanmar were respondents from Southeast Asia; in other words, fellow ASEAN members. Respondents from South America were significantly less interested in Myanmar than other sub-regions in the Asia-Pacific. Business respondents were much more interested in Myanmar than those from the government or the non-government sectors.

integrated into the broader Asia-Pacific economy, Myanmar was ranked as the 6th best opportunity for growth. Some 23 percent of respondents selected Myanmar as a top 5 opportunity for growth. However, there were very wide variations of views. Those most interested in Myanmar were respondents from Southeast Asia; in other words, fellow ASEAN members. Respondents from South America were significantly less interested in Myanmar than other sub-regions in the Asia-Pacific. Business respondents were much more interested in Myanmar than those from the government or the non-government sectors. views on protectionism and income inequality as risks to growth. Income inequality was already concern before the economic crisis struck but has been exacerbated by the crisis.

views on protectionism and income inequality as risks to growth. Income inequality was already concern before the economic crisis struck but has been exacerbated by the crisis.

is limited to ASEAN members only, is nonetheless considered as the most promising pathway to a free trade area in the Asia-Pacific, followed by the East Asian Free Trade Area and then the Trans- Pacific Partnership agreement. The relatively newer concept of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) launched by ASEAN in November 2011 ranked rather low. However, it may be too early for such a judgment as the details of the mechanics of the RCEP are yet to be decided let alone socialized among the broader community. Close to 20 percent of respondents selected ‘Don’t know” in evaluating RCEP.

is limited to ASEAN members only, is nonetheless considered as the most promising pathway to a free trade area in the Asia-Pacific, followed by the East Asian Free Trade Area and then the Trans- Pacific Partnership agreement. The relatively newer concept of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) launched by ASEAN in November 2011 ranked rather low. However, it may be too early for such a judgment as the details of the mechanics of the RCEP are yet to be decided let alone socialized among the broader community. Close to 20 percent of respondents selected ‘Don’t know” in evaluating RCEP.

is a good deal of convergence on top priorities for the APEC Leaders’ meeting: non-government respondents, unlike government and business, include financial sector regulatory reform as a top- 5 issue, while government and non-government included regional cooperation to foster innovative growth and respondents from the business sector included regulatory impediments to business in their top-5 list.

is a good deal of convergence on top priorities for the APEC Leaders’ meeting: non-government respondents, unlike government and business, include financial sector regulatory reform as a top- 5 issue, while government and non-government included regional cooperation to foster innovative growth and respondents from the business sector included regulatory impediments to business in their top-5 list.