Chapter 2 - Survey of Asia-Pacific

Opinion-Leaders*

* Contributed by Eduardo Pedrosa

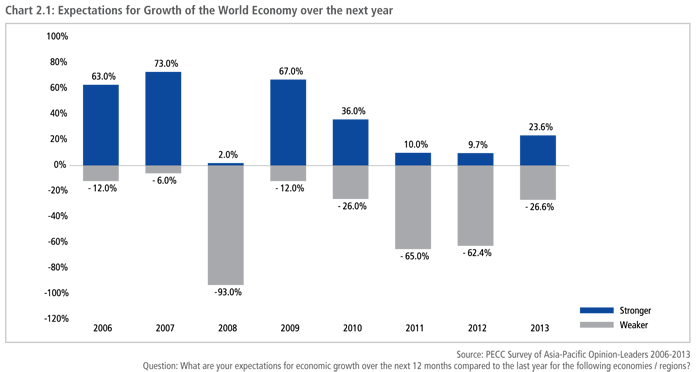

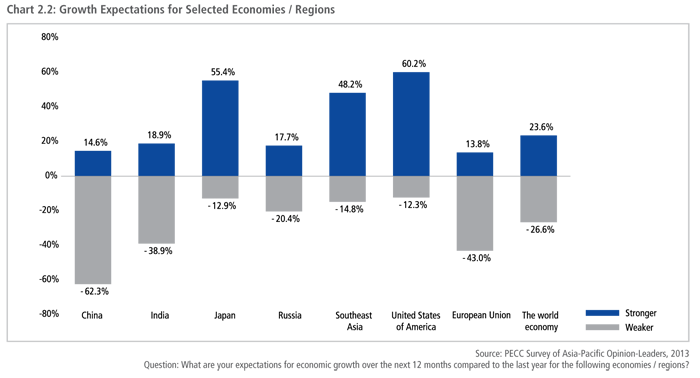

After two consecutive years of negative views on the prospects for growth of the global economy, regional opinion-leaders are fairly evenly split between optimists and pessimists. About a quarter of respondents expect global growth to be either weaker or stronger with a large plurality of expecting growth to remain the same over the next 12 months.

This chapter is based on the findings of PECC’s 2013 survey of 560 Asia-Pacific opinion-leaders conducted from 9 July to 5 August. Responses came from 28 Asia-Pacific economies including all 21 APEC members. Twenty eight percent of respondents were from the business sector, 20 percent from the government, and 52 percent from non-government (including analyst, civil society and the media).

Views on the Economic Outlook

There were however marked differences in views on the global outlook depending on region and profession. East Asians, particularly Southeast Asians were more pessimistic about growth, with 31 percent expecting weaker global growth, while those from the business community were more pessimistic than their counterparts in both the government and non-government with 29 percent expecting weaker global growth.

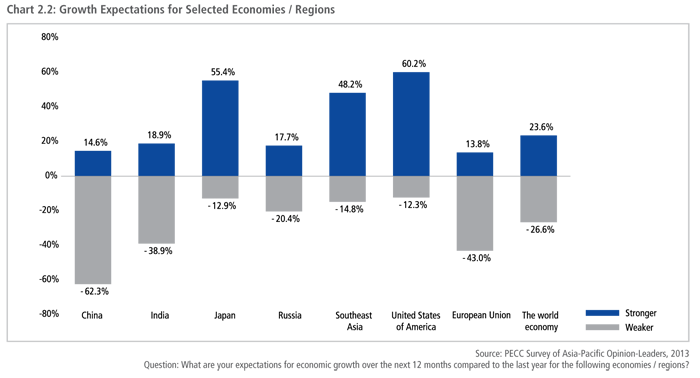

Respondents were most pessimistic about the prospects of growth in China, with 62 percent of respondents expecting a slowdown over the next year. A smaller but still significant proportion also expected slower growth in India. Views remain negative on the European Union with 43 percent expecting weaker growth again over the next 12 months. Sentiments about the US economy have now fully shifted to positive, with 48 percent expecting stronger growth.

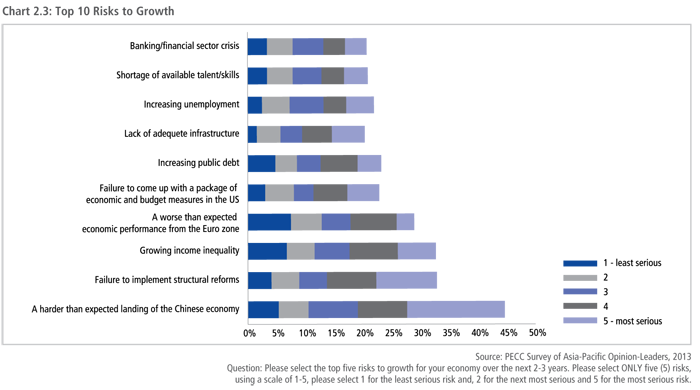

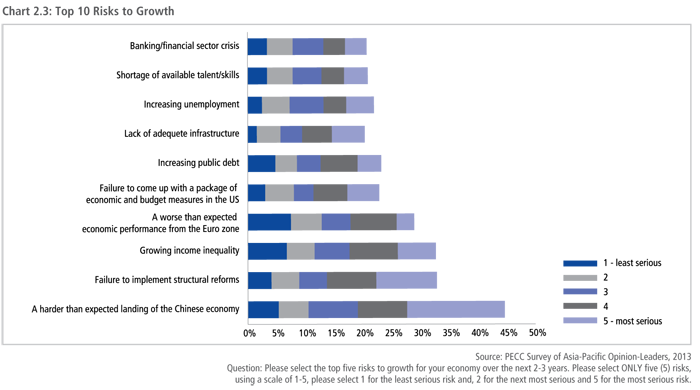

The concerns over the growth prospects in China are similarly reflected in views on the top risks to growth with close to 44 percent of respondents picking a harder than expected landing of the Chinese economy as a top five risk to growth, making it the highest risk this year. The top five risks were:

- A harder than expected landing of the Chinese economy;

- Failure to implement structural reforms;

- Growing income inequality;

- A worse than expected economic performance from the Euro zone; and

- Failure to come up with a package of economic and budget measures in the US.

Of the top 5, the concerns over economic developments in China, the US and EU were also ranked as the highest risks in last year’s survey. Of concern is that income inequality has moved up from the fifth highest risk in 2012 to the third highest. The failure to implement structural reforms is a new risk to growth in the annual survey that it ranked as the second highest risk highlights the need for regional economies to move faster from emergency measures to hold up aggregate demand to undertaking serious policy reforms.

Priorities for APEC

When regional leaders gather in Bali in October, in addition to dealing with pressing issues that dominate concerns at that time, they will also be expected to endorse a number of initiatives that the APEC process has been working on over the course of the year. The last time APEC met in Indonesia, the region adopted the Bogor Goals which have driven the organization’s work for the past 20 years.

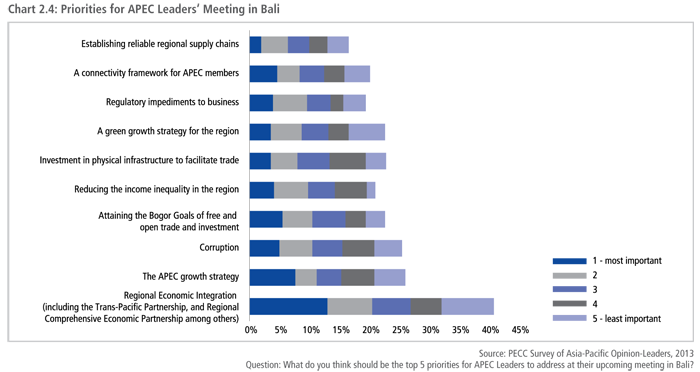

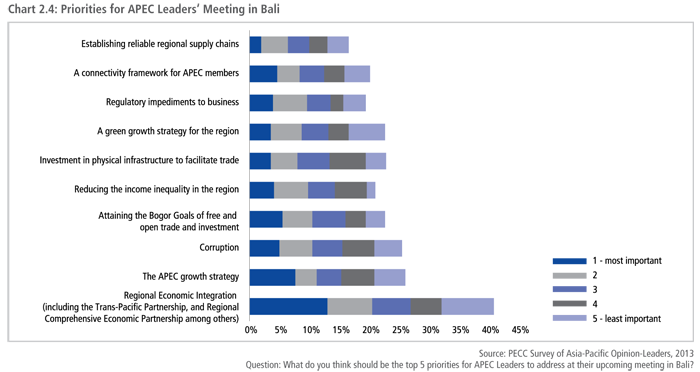

Survey respondents were asked to select and rank the top 5 issues for APEC leaders to address when they meet in Bali. The top 5 were: regional economic integration; the APEC growth strategy; corruption; attaining the Bogor Goals; and reducing income inequality in the region.

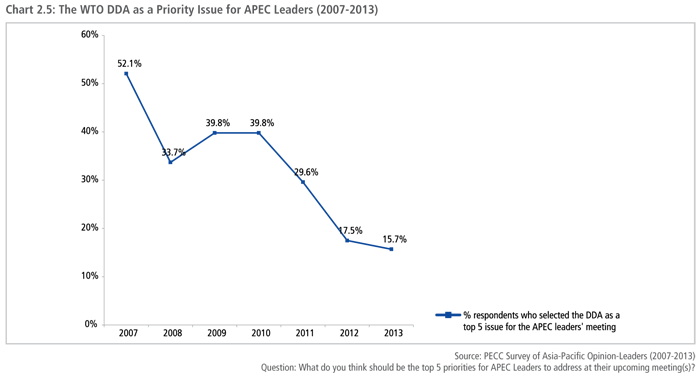

One issue, conspicuous by its absence from the list of priorities is the WTO Doha Round of trade negotiations. This latest round, launched in 2001, has dragged on for 12 years missing multiple deadlines. While it is most probable that APEC leaders will have to address this critical issue, the low ranking of the issue in the list of priorities is a testament to the lack of support for spending time on discussing the issue. There is currently a clear preference, at least among regional opinion-leaders for spending time on regional economic integration initiatives such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

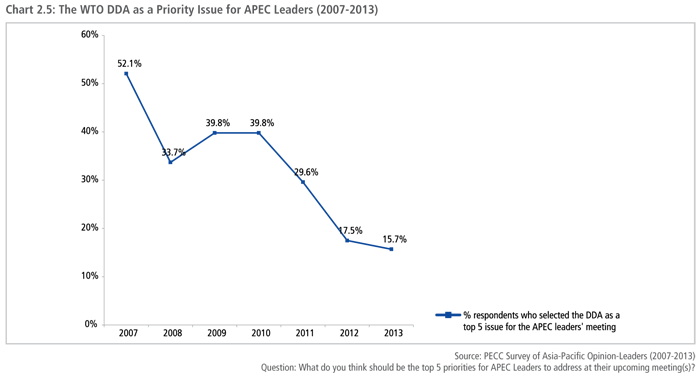

The WTO DDA has steadily dropped as a priority for APEC leaders over the years from a high of 52.1 percent in 2007 to a low of 15.7 percent this year. Of even greater concern is the lack of interest from the business community, only 10.9 percent of whom thought APEC leaders should spend time discussing the Round, compared to 37.2 percent who thought time should be spent on regional economic integration and corruption. However, views on the WTO were not evenly shared through the region. Government respondents rated the WTO DDA as the 7th highest priority for APEC leaders to address with 21.6 percent of them selecting it as a top issue. Even though there seems to be little support for spending the time of Leaders on this issue, the potential benefits of a breakthrough, even a limited one are high. For example, a WTO agreement on trade facilitation could increase global GDP by as much as US$1 trillion, with most of the benefits going to developing economies.

Perhaps more importantly there are now serious systemic questions facing the multilateral trading system that outweigh estimates of economic benefits. It is clear at least from this survey that high level business support for negotiators to make concessions is going to be limited, the risk for the global system is that the WTO faces a crisis where its primary role as a forum for trade negotiations will be irreparably damaged. This would leave further concessions to preferential trade deals, which inevitably leave those not involved in the agreement facing reduced market access. This is a time when, in spite of limited support from the business community, government officials should be taking a leadership role to find a breakthrough.

The APEC Growth Strategy

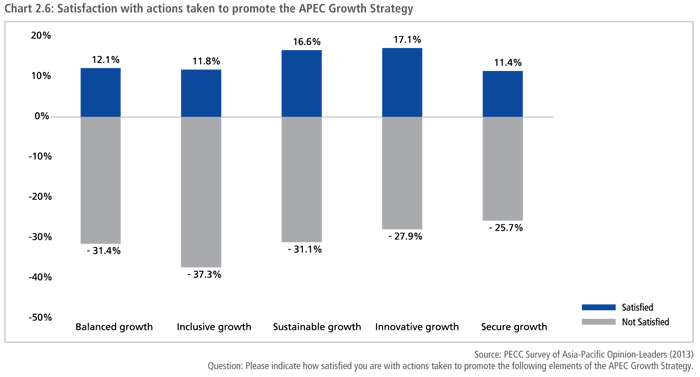

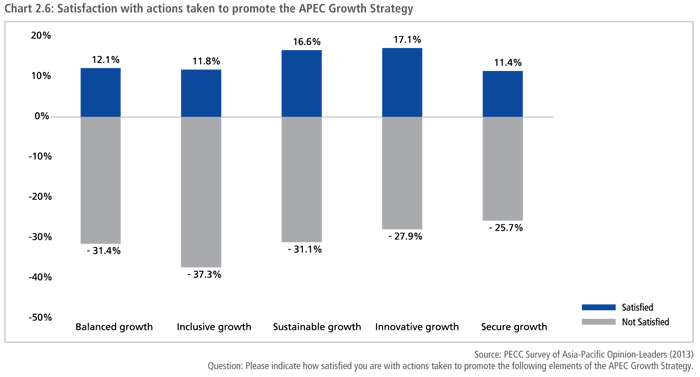

In 2010, APEC leaders recognized that the region cannot continue with ‘growth as usual’ and ‘the quality of growth’ needs to be improved, so that it will be more ‘balanced, inclusive, sustainable, innovative, and secure.’

Some three years after the adoption of the strategy, in none of the five dimensions did respondents express more satisfaction than dissatisfaction with actions taken thus far. While APEC has been addressing different aspects of the growth strategy since it was adopted, for example, agreeing on a reduction on tariffs on environmental goods to promote sustainable growth and developing frameworks for innovation, implementation of these agreements is yet to happen.

Trade and Development

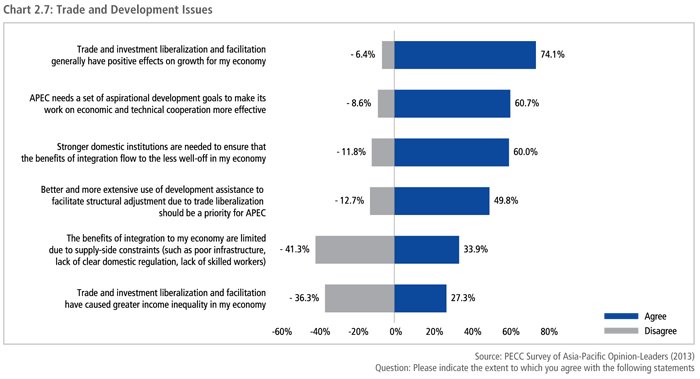

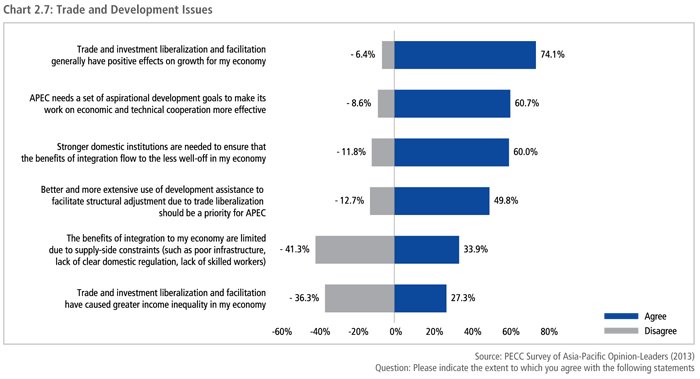

The survey results show continued strong support for APEC’s work on trade and investment liberalization with close to 75 percent of respondents agreeing that it has had positive effects on growth for their economy. At the same time, there was broad support for the assertion that stronger domestic institutions are required to ensure that the benefits of the integration process flow to the less well-off in society.

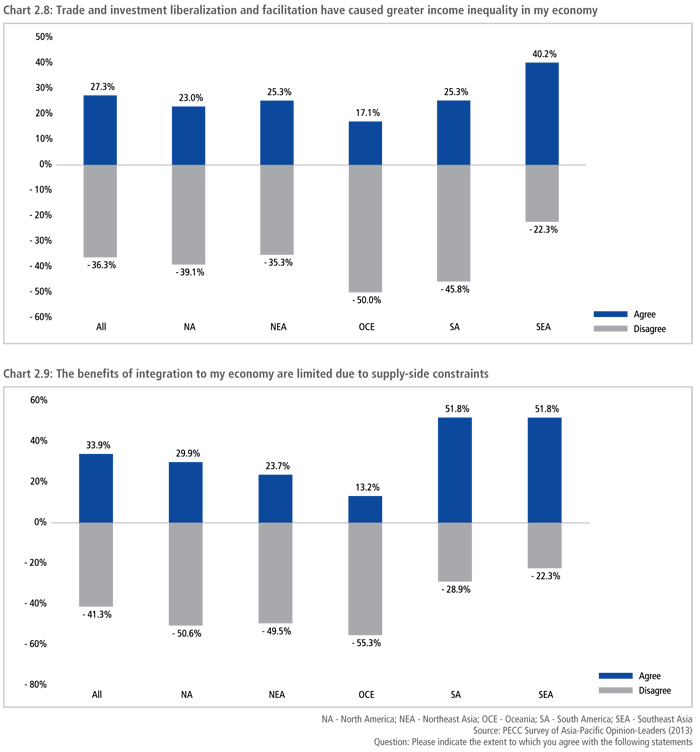

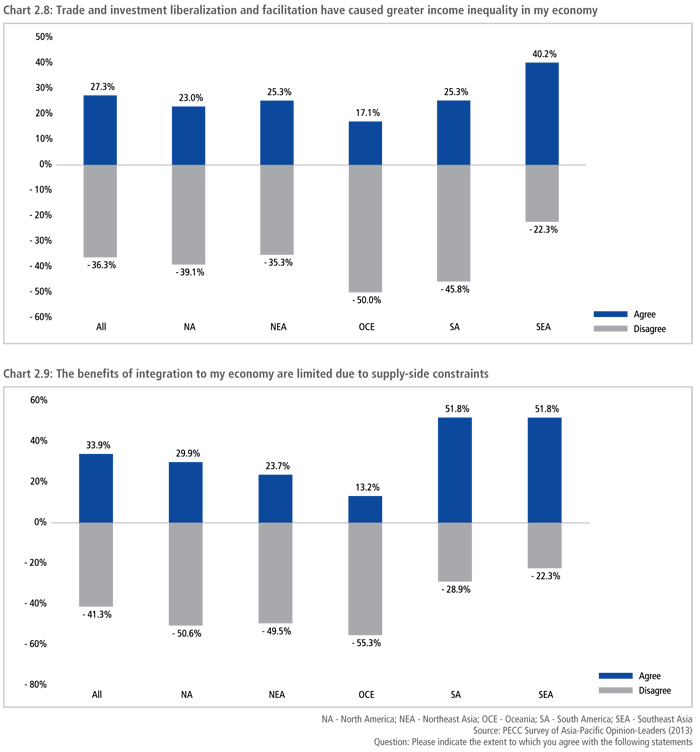

While most respondents did not agree with the assertion that trade and investment liberalization and facilitation have caused greater income inequality, those from Southeast Asia tended to agree that there is a connection between the two.

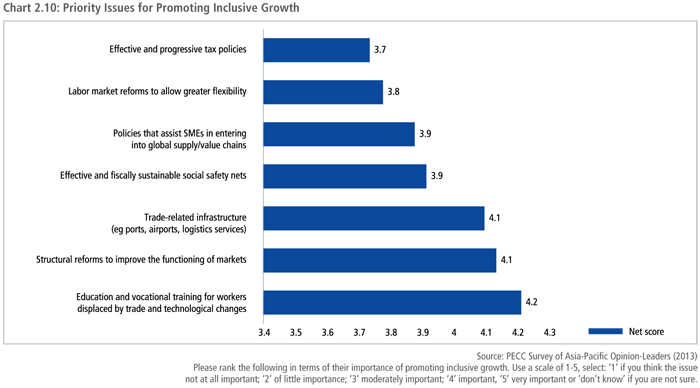

There was a similar difference of views on whether the benefits of integration to have been limited due to supply-side constraints such as poor infrastructure, lack of clear domestic regulation, lack of skilled workers. Respondents from South America and Southeast Asia tended to agree with the statement while those from more developed regions disagreed.

While there was disagreement in so far as how the integration process has affected income distribution within economies and the causes, there was broad agreement that APEC should have a set of aspirational goals to drive its work on economic and technical cooperation and it should improve and make more use of development assistance to facilitate structural adjustment due to trade liberalization.

Promoting Inclusive Growth

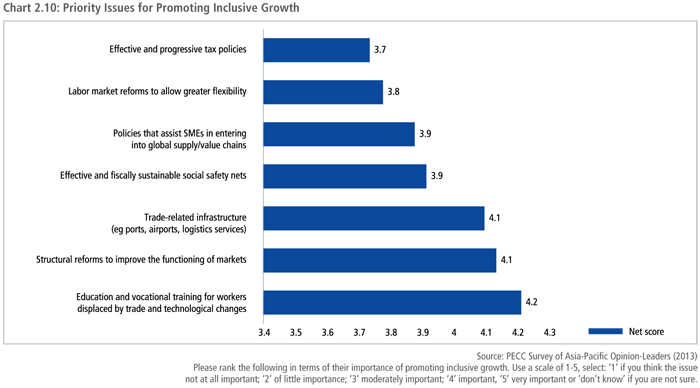

Opinion-leaders ranked education and vocational training as the most important way of promoting inclusive growth followed by structural reforms and then trade-related infrastructure. Tax policies and labor market reforms ranked lower in terms of importance. Overall, there was broad agreement on priorities with some differences in emphasis, for example, on how much of a priority should be placed on policies to assist SMEs with those from Southeast Asia ranking it a high 4.2 and those from Oceania at 3.5.

While effective and progressive tax policies ranked lowest overall on the list of policies to promote inclusive growth, there were marked differences in views on this issues among sub-regions, with some 66 percent of respondents from Oceania rating it as a priority issue compared to just 37 percent in Northeast Asia.

Development Goals

Over 50 percent of respondents agreed that APEC needed to have a set of aspirational development goals to make its work on economic and technical cooperation more effective. Such an approach has been taken by APEC in the past. For example, the Bogor Goals set in 1994 included an aspiration to achieve free and open trade and investment in the region by 2020, as well as specific targets set for reducing transactions costs through trade facilitation action plans. More specifically on development issues, in 2000, APEC leaders set a target of tripling the number of people with access to the internet by 2005.

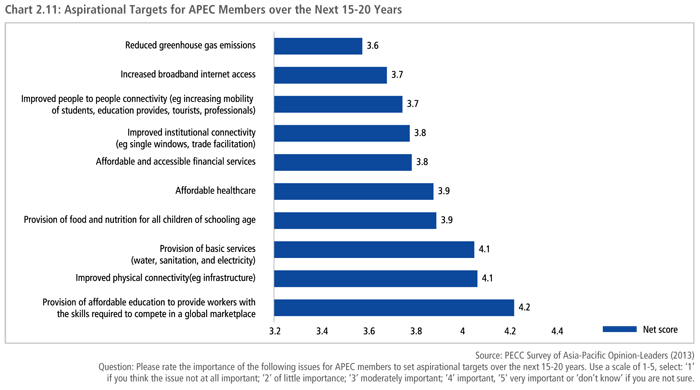

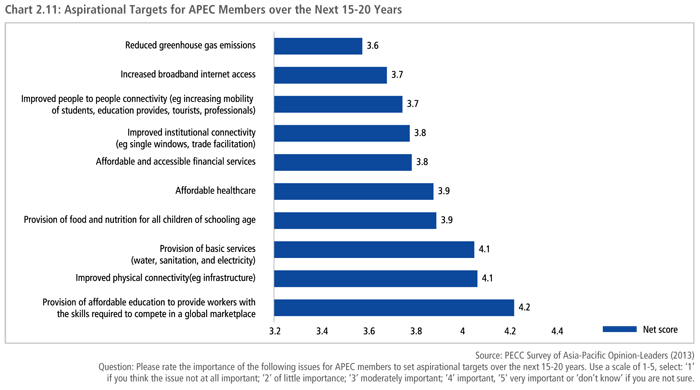

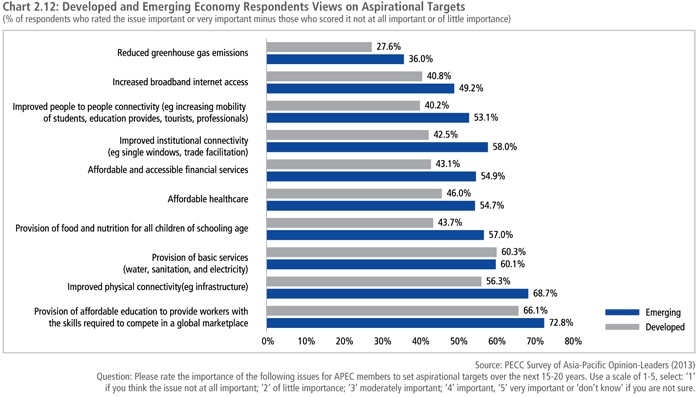

The provision of affordable education to provide workers with the skills to compete in the global market place was ranked as the most important developmental goal for the region followed by physical connectivity and the provision of basic services.

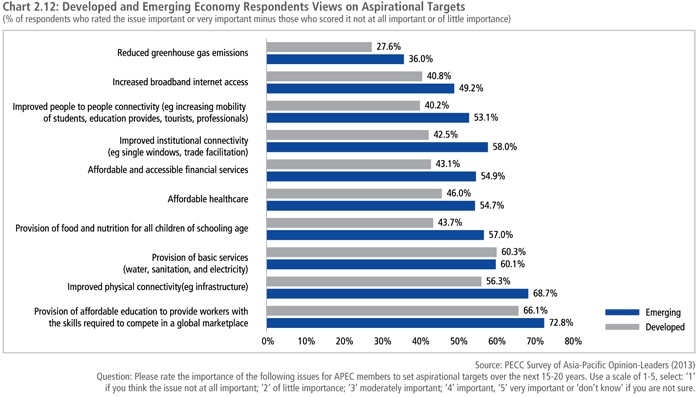

Overall, respondents from emerging economies placed a higher level of importance on development issues than their counterparts from developed economies. The gap in views was largest on improved institutional connectivity followed by the provision of food and nutrition for school children and then improved physical connectivity.

While noting that there are differences in how respondents from developed and emerging economies rated issues, there were fewer differences in the ranking of issues. For example the top three issues selected by both groups were the same:

- Provision of affordable education to provide workers with the skills required to compete in a global marketplace;

- Improved physical connectivity (eg infrastructure); and

- Provision of basic services (water, sanitation, and electricity).

One major difference was the ranking of the provision of healthcare which was the fourth most important goal for those from developed economies and only the seventh for those from emerging economies.

The underlying proposition is whether APEC needs to set aspirational targets fort development with the further question of what those targets should be. The survey results show that there is clear support for the proposition as well as a high level of agreement on at least some of the goals – especially education. Given that the international community is formulating post-2015 Millennium Development Goals, the Asia-Pacific which accounts for both the largest part of the global population as well as economic output, APEC could make a valuable contribution in this area, especially where such targets address the key concern of increasing income inequality.

Regional Institutions

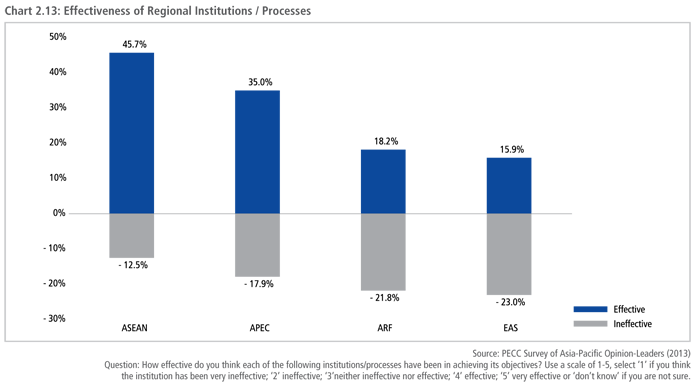

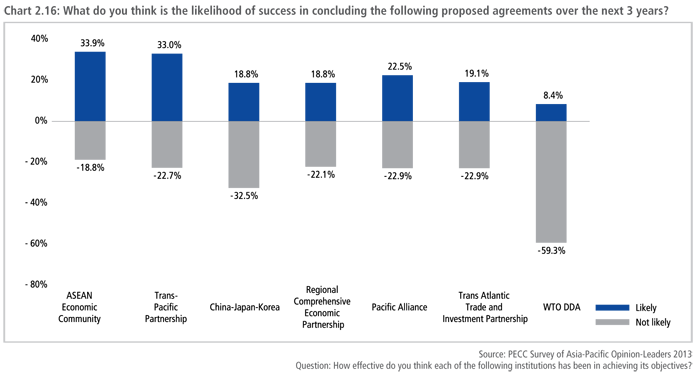

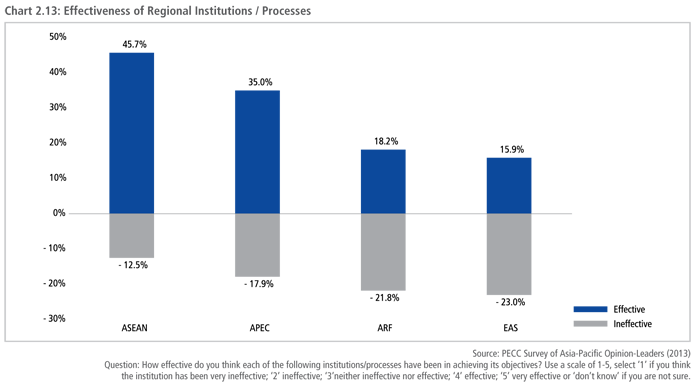

The Asia-Pacific region is now host to a growing number of institutions some of whose memberships and mandates overlap. ASEAN was rated as the most effective with 46 percent of respondents rating it as effective and 12 percent as ineffective. APEC is then considered the next most effective with 35 percent rating it as effective and 18 percent as ineffective. Only 16 percent of respondents rated the East Asia Summit (EAS) as effective.

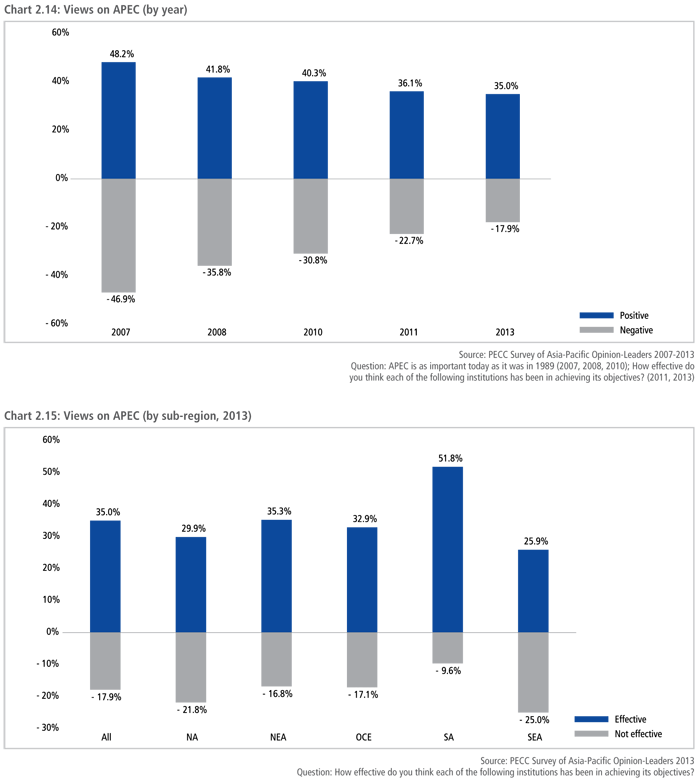

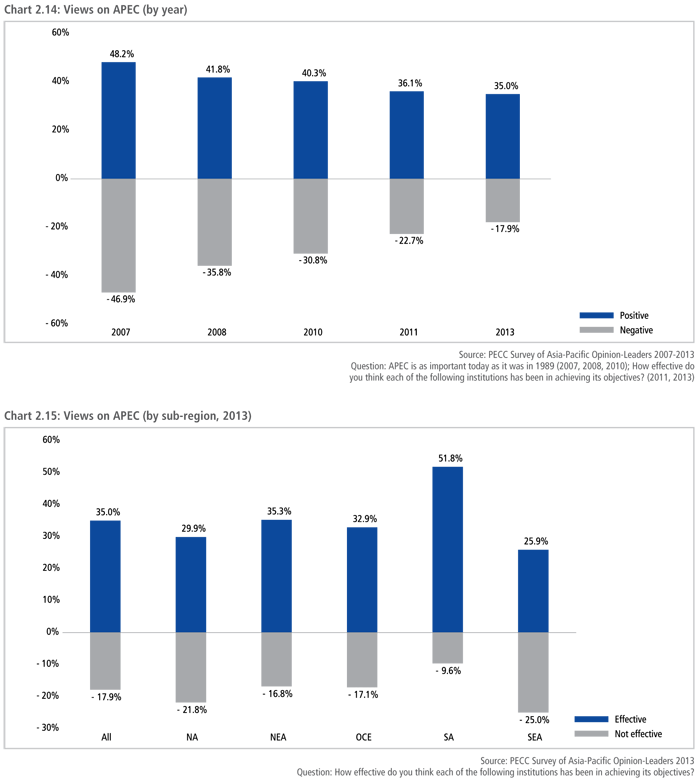

Over the course of the past few years, PECC has surveyed views on APEC ranging from its effectiveness to whether it is as important as it used to be, the results while answers to different specific questions can be broadly grouped into those with ‘negative’ and those with ‘positive’ views. Over the past 6 years the net approval for APEC has steadily moved upwards to 17.1 percent this year compared to a net approval of just 1.3 percent in 2007.The improved approval rating has been a large reduction in those with negative perceptions of APEC, going down from 47 percent to 18 percent over the period. However, at the same time, those with positive views have gone down but at a much slower rate from 48 percent to 36 percent.

Respondents from South America had by far the most positive views of APEC with 52 percent of respondents rating it as an effective institution compared to around 10 percent of those who thought it ineffective. Worryingly, only 26 percent of respondents from Southeast Asia rated APEC as effective with an almost equal number rating it as ineffective.

Given the critical role that ASEAN plays in regional processes, this finding requires further examination. While efforts have been to coordinate APEC and ASEAN activities, there is much more that could be done. Another reason for the low ranking given by respondents from ASEAN could be the development of the East Asia Summit process which some commentators have argued duplicates APEC’s footprint. However, while ASEAN respondents show some ambivalence about APEC, they are equally ambivalent, if not negative, about the EAS, giving it a net disapproval of 5.4 percent.

The strongest ‘approval’ for APEC’s work comes from government officials with 50 percent considering it an effective institution. There was a substantial gap between their assessments and stakeholders from the business and non-government sectors, of whom 14 and 10 percent rated APEC as an effective institution respectively.

Regional Economic Integration

In 2007 APEC leaders agreed to examine the options and prospects for a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) and in 2010, they agreed that an FTAAP should be pursued as a comprehensive free trade agreement by developing and building on ongoing regional undertakings, such as ASEAN+3, ASEAN+6, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), among others.

By the time APEC leaders meet in Bali, the Trans-Pacific Partnership will have completed 19 rounds of negotiations. Japan, the region’s third largest economy became the 12th member of the group earlier this year which now accounts for about 66 percent of the region’s economic output and 50 percent of its exports.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) grouping of 16 economies includes all ASEAN members plus its existing FTA partners - Australia, China, India, Japan, Korea and New Zealand) accounts for just under 50 percent of the region’s economic output and close to 60 percent of its exports. The RCEP has begun its negotiations and has set a target of completion at 2015.

In addition to the TPP and the RCEP there are a number of on-going large scale trade negotiations that include Asia-Pacific economies, including the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the United States and the European Union, the Pacific Alliance which includes South American economies on the Pacific Rim, the China- Japan-Korea (CJK) agreement, and the WTO Doha Round.

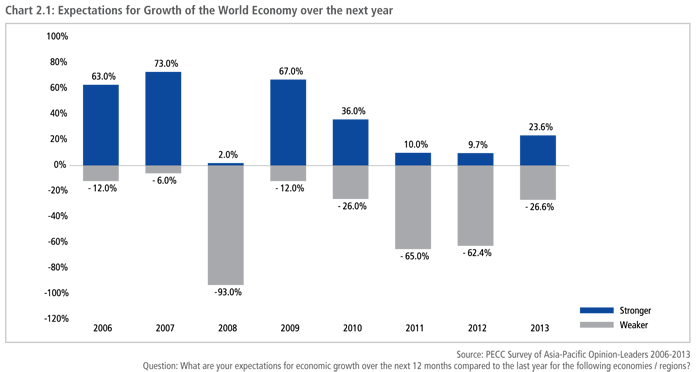

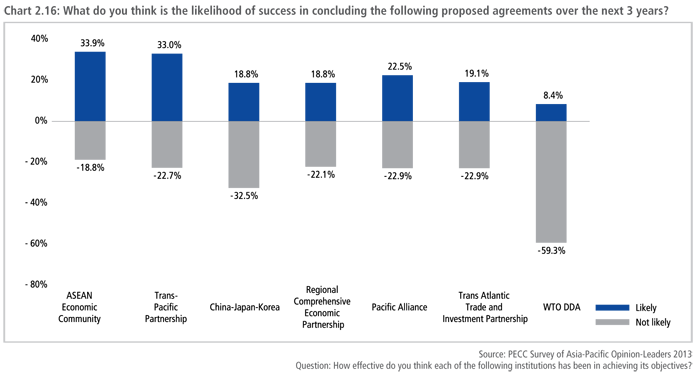

Of all of these agreements, regional opinion-leaders were only positive about the likely conclusion of the AEC and the TPP by 2015. They were by far the least optimistic about reaching a conclusion the WTO DDA with 59 percent stating it was not likely and only 8 percent stating likely. While opinion-leaders were pessimistic about the conclusion of the RCEP with 3.4 percent more respondents thinking it would not likely reach a conclusion by 2015 than those who thought it would likely reach a conclusion, this is a significant improvement over last year’s survey result which had 19.3 percent more respondents on the negative side.

The question posed in this year’s survey is slightly different from that of 2012 in that includes a specific deadline – the next three years. However, the addition of a timeline to the question did not significantly change views with opinion-leaders most optimistic about a successful conclusion for the AEC followed by the TPP.

An important footnote to the findings is the high level of respondents who select ‘don’t know’ for specific agreements – notably the RCEP and the Pacific Alliance. In the 2012 survey 18.4 percent of all respondents selected ‘don’t know’ for the RCEP while in this year’s survey it was 17.1 percent. For the Pacific Alliance 22 percent of respondents selected ‘don’t know’. There may be different reasons for willingness to venture an opinion on the likelihood of success of an agreement. It might be argued that respondents come from economies who are not parties to the agreement, in the case of the Pacific Alliance, this seems to be the case, with a very high 29 percent of Southeast Asian and 16 percent of Northeast Asians selecting ‘don’t know’. However, in the case of RCEP, some 7 percent of Northeast Asians and 19 percent of Southeast Asians selected ‘don’t know’ in assessing the likelihood of a conclusion by 2015.

Regional opinion-leaders were also negative on the prospects of reaching a successful conclusion of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the United States and the European Union. As with the RCEP and the PA, there was a high level of lack of awareness with 21 percent selecting ‘don’t know.’

The only inference that can be drawn from this is that the new agreements need a lot more socialization. Bearing in mind that the survey draws on the views of opinion-leaders who actively follow Asia-Pacific economic affairs, the lack of awareness should be a high concern to policy-makers.

Time for a Regional Focus on Development

While sentiments on the economic growth are turning positive there are substantial risks to the outlook. Opinion-leaders are worried about prospects for growth in China and the possibility of policy failures in the United States, the high amount of concern about a failure to implement structural reforms and growing income inequality point to a useful agenda for regional cooperation processes.

As discussed in Chapter 1 of this report, while a recovery does seem to be underway, a return to the high growth of the pre-crisis period is not on the cards especially growth reliant on exports. The high degree of support for developmental goals evident in the survey results reflects the concerns about growing inequalities within and among regional economies. While there are differences in views on specific priorities, opinion-leaders from both emerging and developed economies share a desire to see APEC take a more active leadership role in promoting development cooperation. This type of agenda focused on the quality of growth should be seen as strongly supportive of APEC’s traditional work on regional integration. While views on APEC’s effectiveness are improving, that opinion-leaders in emerging economies, especially Southeast Asia, hold negative views should be taken as a wakeup call.