Chapter 2:The New Generation of ‘Digital’ Trade Agreements: Fit for Purpose?

Peter Lovelock47

The digitalization of the economy necessitates governments align their domestic laws and policies and liberalize their markets to achieve greater connectivity and exchange of information across borders. A key driver among economies working towards such alignment is the goal of improving economic and social growth by exploiting the enormous opportunities enabled by digital trade. The growth of digital trade is dependent upon greater interconnectivity and interoperability across jurisdictions.

Digital trade integration, however, is a complex, multidimensional process that integrates regulatory structures and policy designs, digital technologies and business processes along the entire global digital value chain. It requires free cross-border movement of not only digital services, products and technologies but also other manufactured goods (e.g. internet platform-driven trade), data, capital, ideas, talent as well as the availability of integrated physical and virtual infrastructure. Thus, digital trade integration is not only dependent on the removal of digital trade barriers but also requires extensive technology, legal and policy coordination. Economies thus strive to achieve such interconnectivity and integration in digital trade through international trade agreements.

Recent trade agreements have begun including or focusing upon provisions to reduce regulatory barriers in digital trade and facilitate cross-border trade-in-data. However, at a time when digital demand and use are seen to be growing exponentially, and governments are focusing on accelerating their domestic digital economy growth, often accompanied with programs of digital transformation or digital government, regulatory restrictions on international digital trade are growing equally, if not more, rapidly. If the growth of domestic digital economies is to at least some extent dependent upon and underpinned by digital trade (the flow of cross-border data and the trade-in-data), then how to resolve this apparent contradiction?

Are these emerging FTAs, like their in-existence forerunners, deficient in supporting digital development and inclusion as well as fostering widespread international regulatory cooperation? It is obviously too early to judge what are very worthwhile approaches too harshly. However, as the proliferation of digital regulatory innovation and restriction illustrates they are very open to both negative and positive interpretation and, thus far, appear unable to facilitate a holistic digital trade regulatory framework given the conflicting domestic privacy and cybersecurity laws among trading partners.

Seizing the opportunity presented by digital trade, and realizing its potential for economic growth, will however depend on the development of harmonized trade rules. Trade rules will help remove a host of barriers impeding trade such as cross-border data flow restrictions, localization requirements, tariffs and quotas on ICT equipment, domestic and local standards that deviate from international standards, and lack of access to effective dispute resolution mechanisms.

Recognizing the above, this brief review of the current slate of digital trade agreements, began from the question of how similar are each of the agreements in their digital provisions, and the digital language being used? Is the language truly similar, or are there gaps and differences across these agreements – which may begin to explain some of the constraints we see in fostering digital trade. If so, what are these gaps? This led to a further question as to whether the approach being adopted – adapting and amending FTAs to incorporate a digital chapter or digital provisions is the appropriate means for developing a digital trade environment? And if so, what language was emerging that deserves to be “baked in” to such agreements going forward?

The New ‘Digital’ Trade Agreements

The past two years has seen the emergence of five key ‘digital’ trade agreements: the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) are existing FTAs updated and modified to include chapters on e-commerce and digital trade respectively. The remaining three – the US-Japan Digital Trade Agreement (Digital Trade Agreement); the Singapore-Chile-New Zealand Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA); and the Singapore- Australia Digital Economy Agreement (SADEA) – are positioned as ‘digital-only’ trade agreements.

These plurilateral agreements seek to develop international frameworks that harmonize digital trade rules, enhance cooperation on international standards, and create interoperable systems. In reality, they share much in common with traditional trade agreements in both format and language. A key question has become: does the current language being deployed in ‘digital’ trade agreements reflect and enable the achievement of these objectives? Or is it a limiting constraint – a repacking of new into old boxes?

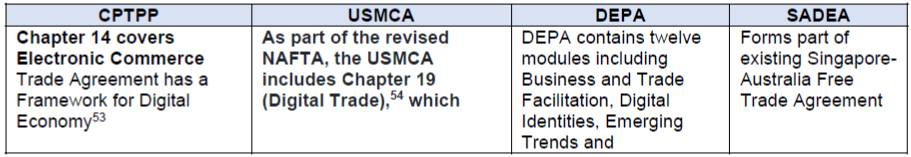

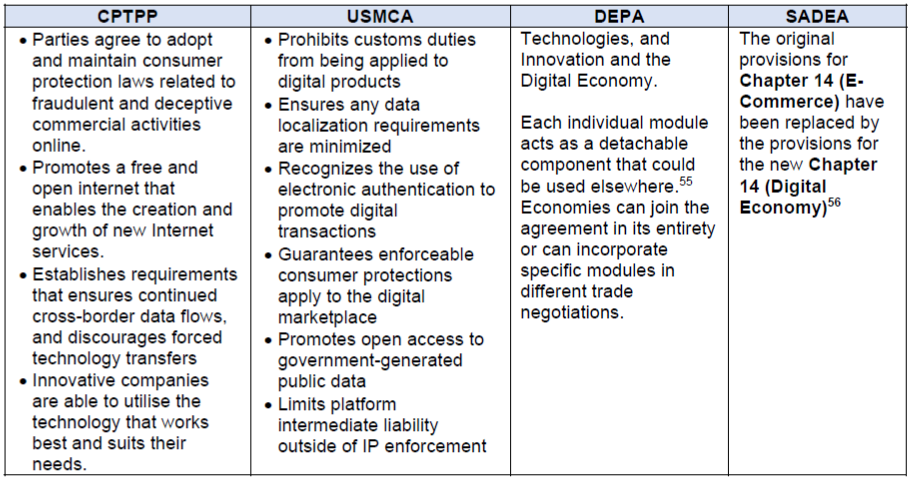

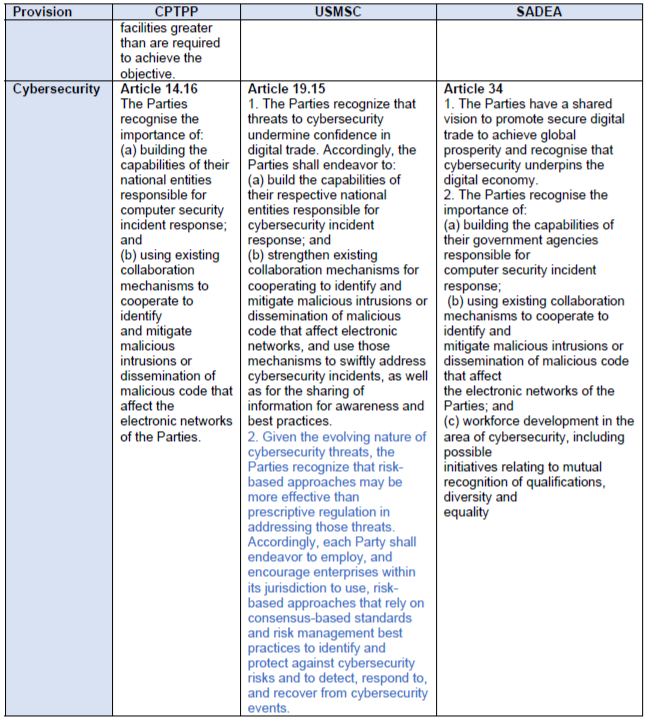

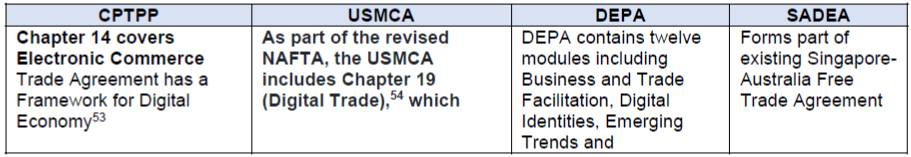

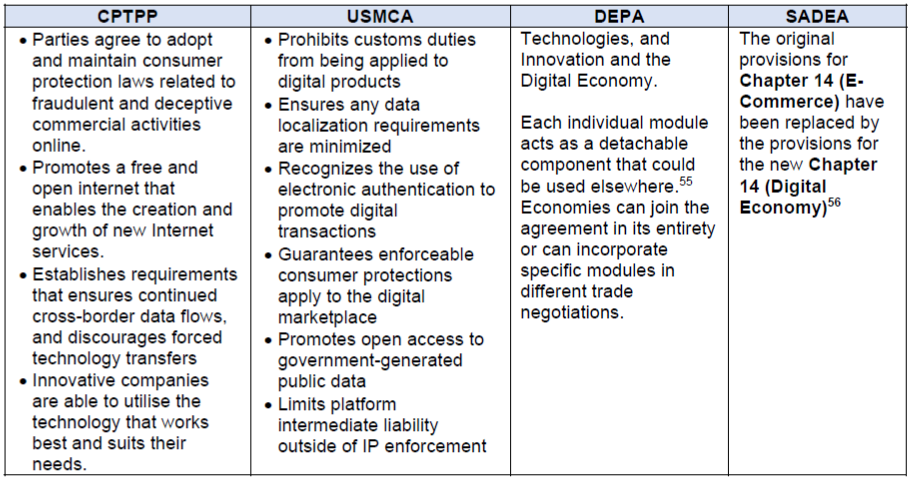

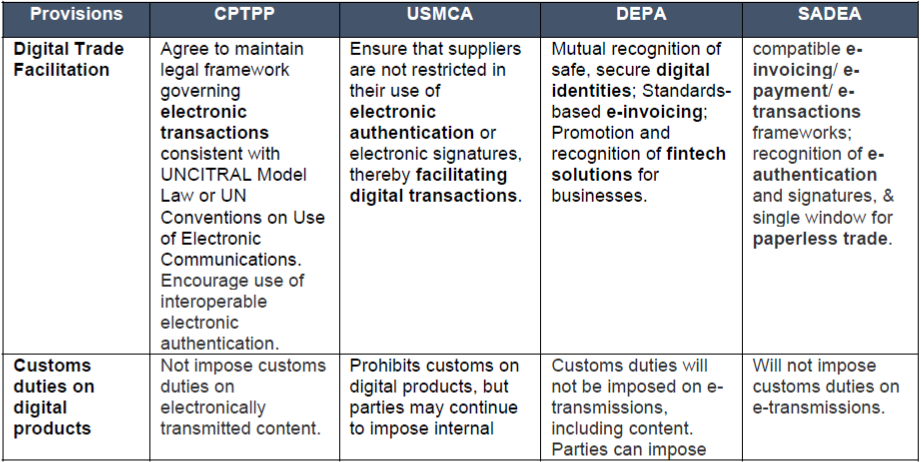

Here we focus on four of the five agreements: the CPTPP, USMCA, the SADEA, and DEPA. A brief description of the four agreements is provided below with a summary of key approaches and objectives in Table 1.

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP): The CPTPP is a free trade agreement between Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. It first entered into force among six economies – Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand and Singapore on 30 December 2018, and Vietnam on 14 January 2019. The four remaining members will enter after they complete their ratification processes. The e-commerce chapter of the agreement sets rules to facilitate digital trade, allowing participating members preferential access to each other’s markets, and includes measures that will promote the flow of data, protection of privacy and consumer rights, and intellectual property.48

US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA): USMCA is a free trade agreement between the United States, Mexico and Canada. It replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and entered into force in all members on 1 July 2020. The agreement includes a chapter on digital trade which builds on the provisions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and includes rules to prohibit customs on digital products, protect the flow of data, privacy, and intellectual property, and promotes collaboration on cybersecurity.49

US-Japan Digital Trade Agreement (US-Japan Agreement): The US and Japan implemented two separate trade deals, the Trade Agreement and Digital Trade Agreement in 2019. The Digital Trade Agreement went into effect on 1 January 2020 and provides guidelines on priority areas of digital trade.50 It parallels the USMCA, and includes key provisions on prohibition of customs duties or other protectionist measures on digital products.

Singapore-Chile-New Zealand Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA): The DEPA was signed on 12 June 2020, between Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. It aims to strengthen cooperation in digital trade, and promote interoperability.51 It is divided into 12 modules that include treatment of digital products, data issues, emerging technologies, digital inclusion, and small and medium enterprise cooperation. It will enter into force once at least two parties have completed relevant domestic processes.

Singapore-Australia Digital Economy Agreement (SADEA): Singapore and Australia signed the SADEA on 6 August 2020.52 Building on existing agreements under the CPTPP and the Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement, it sets a range of trade rules to capitalize on the digital economy. As part of the SADEA, the two economies have signed a series a MoUs on areas including e-invoicing, e-certification, personal data protection and digital identity.

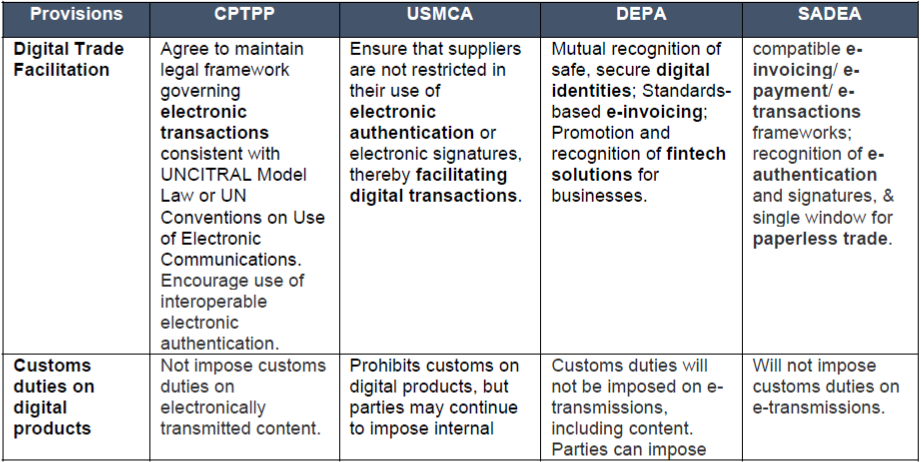

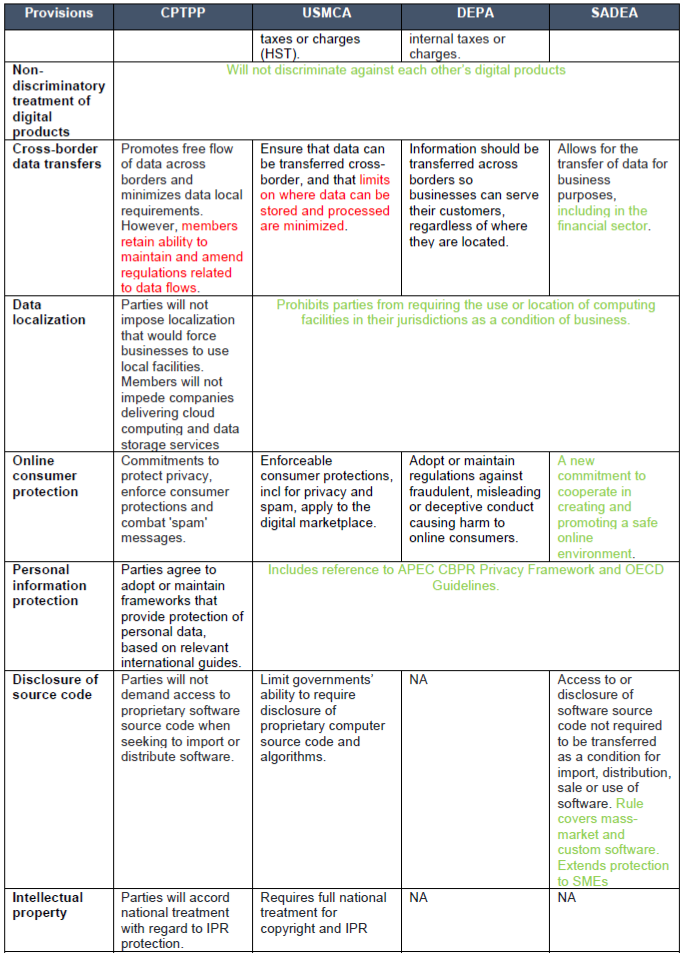

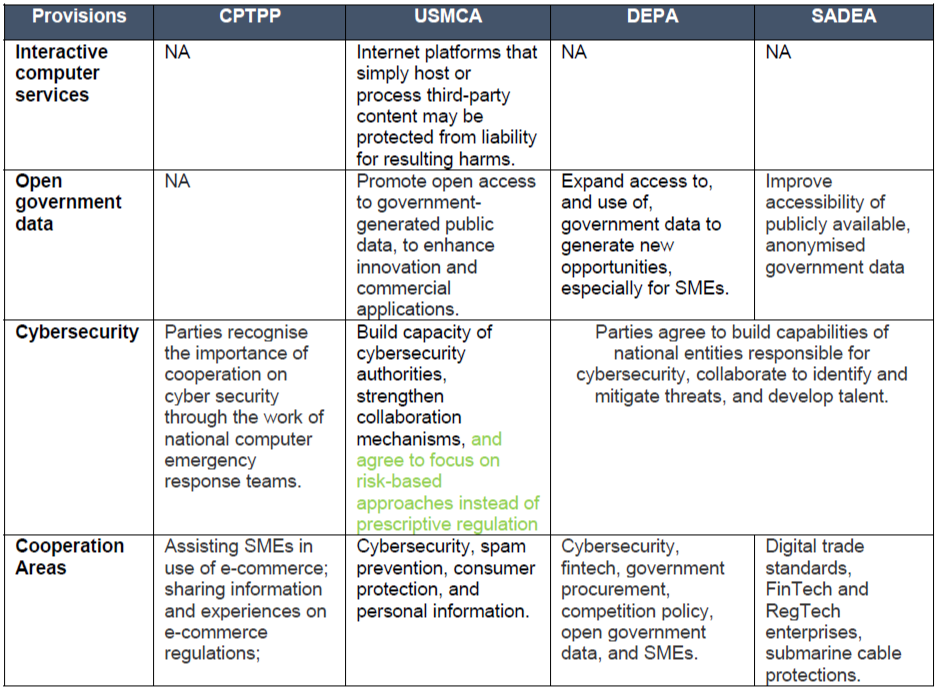

Table 1: Context and Key Provisions of Four Digital Trade Agreements

Similarities in ‘Digital’ Trade Language: A Path Forward?

Much of the commentary around these new ‘digital’ trade agreements has lauded what is seen as an adoption of common principles, and an emerging commonality of language that can be “baked in” to future trade agreements as digital becomes ever more ubiquitous and integral to trade. To the extent that there is a difference in these agreements, it is broadly seen to be one of approach: i.e., either they are amending language within an existing trade agreement (as is the case with the CPTPP and USMCA), or they are distinctly new digital-only agreements (as is the case with DEPA).

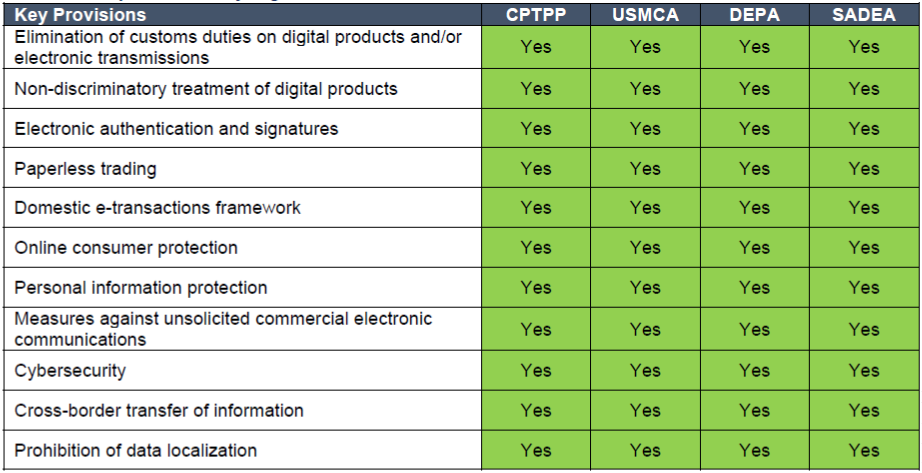

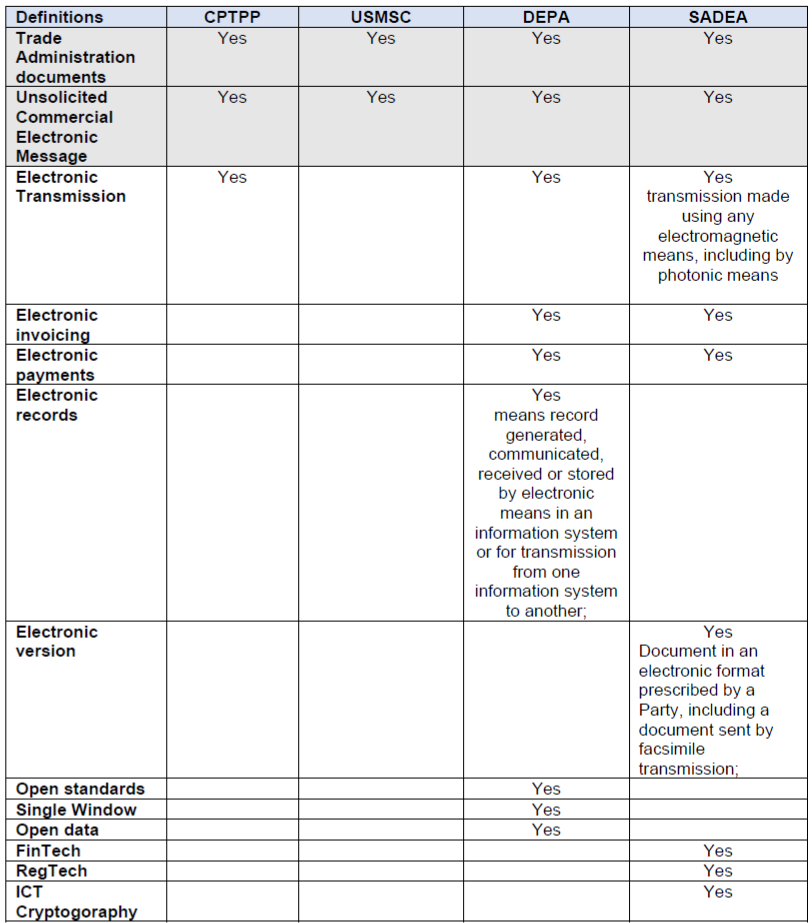

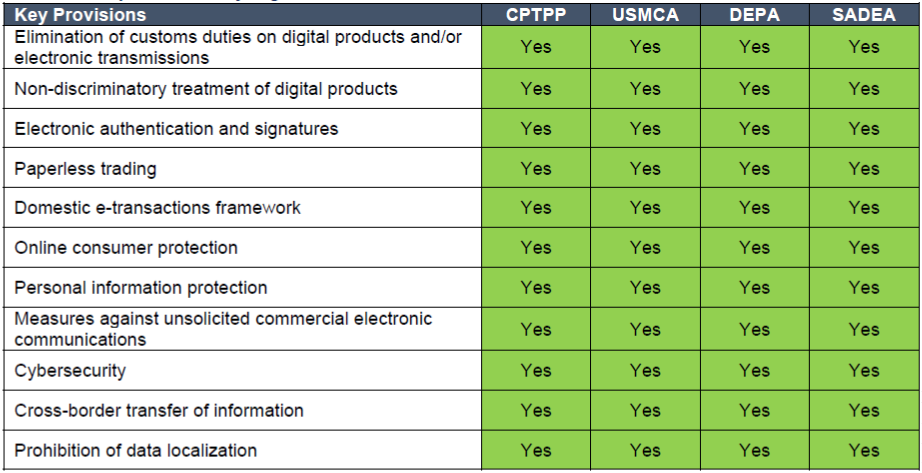

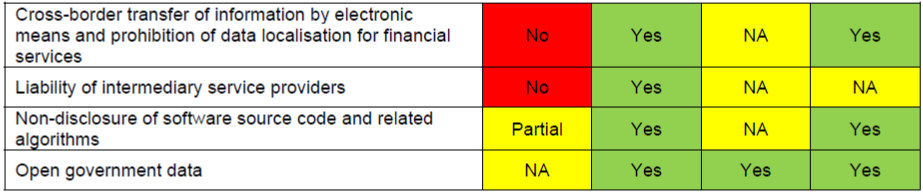

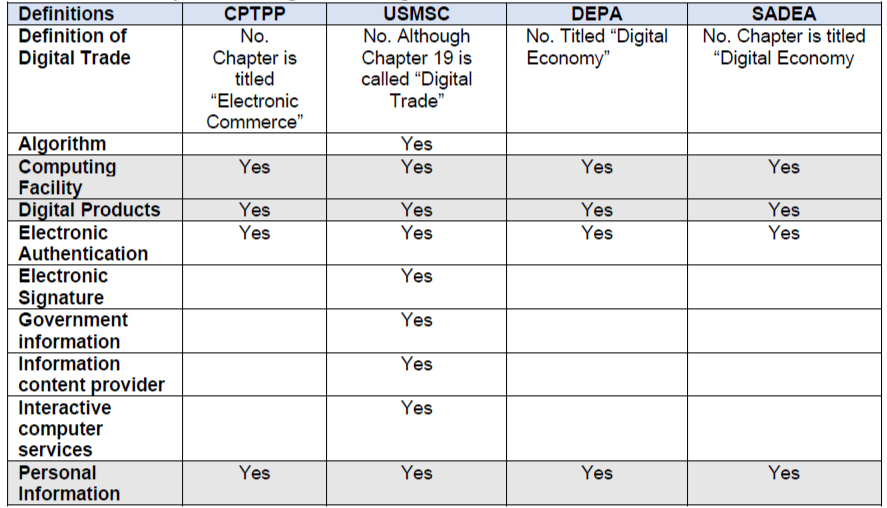

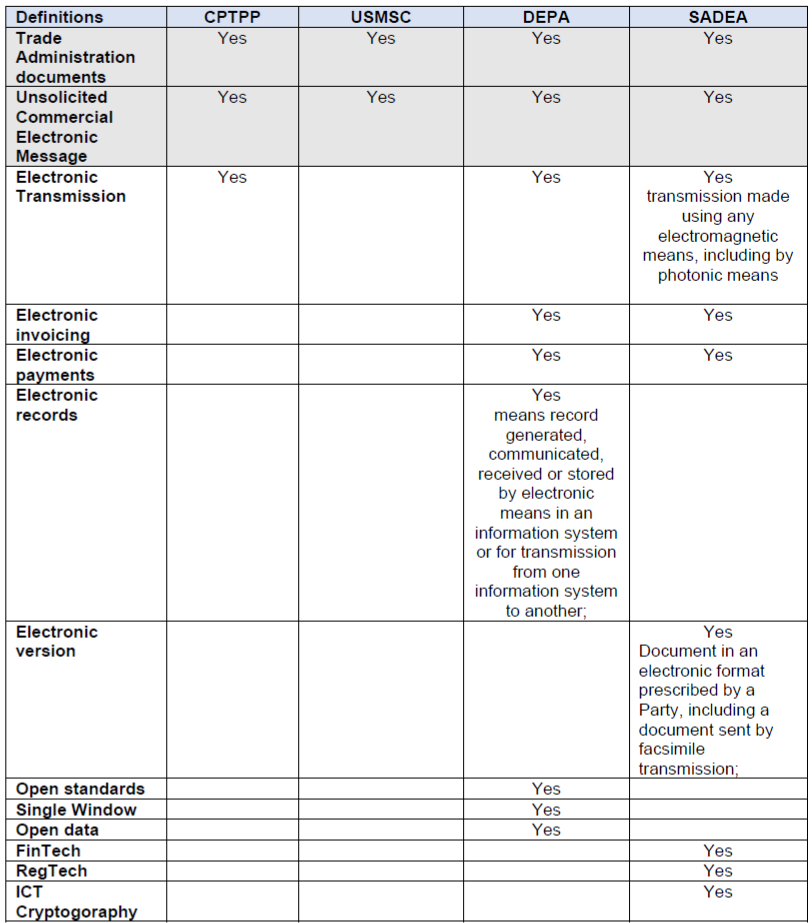

This is often summarized down into a ‘shopping list’ approach – as illustrated in Table 2 – suggesting that there is a common set of digital clauses that are gaining currency and, once recognized, can be input into agreements to ensure protections will be recognized and enforced.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Digital Trade Provisions

Source: Adapted from http://asiantradecentre.org/talkingtrade/comparing-digital-rules-in-trade-agreements

Yes: the provision is included in a separate article and is fully addressed;

No: the provision is included in a separate article, but is not addressed;

Partial: the provision is not fully addressed;

NA: the provision is not mentioned throughout the agreement.

In this telling, the key provisions relating to digital trade are “roughly the same and occur in all agreements”. The “key provisions” captured are indeed key and important issues: customs duties on digital products,non-discriminatory treatment of digital products, cross-border information flows and localization requirements, non-disclosure of source code, e-transactions frameworks, online consumer protection, personal information protection, and cybersecurity. It is recognized that agreements differ “in their treatment of some provisions and the exemptions they offer to members”, which is standard and to be expected for trade agreements.

However, what this shopping list approach fails to capture is potentially as important as the good news story that this apparent recognition of digital suggests. The gaps include the differences in interpretation and language of many of the of these key provisions, the provisions that are not common across the agreements, and the reasons for that, and the continued use of traditional jurisdictional considerations in the interpretation and application of the new digital provisions – most notably through carve outs for “legitimate public policy outcomes” (LPPOs), and domestically strategic sectors (such as finance, healthcare, education, communications and national security).

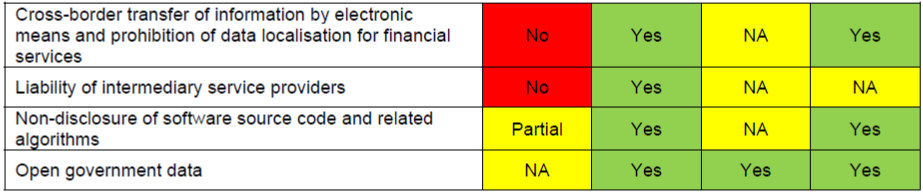

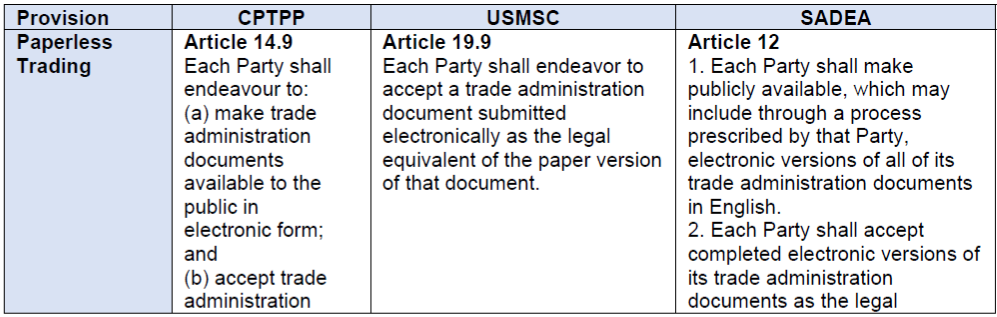

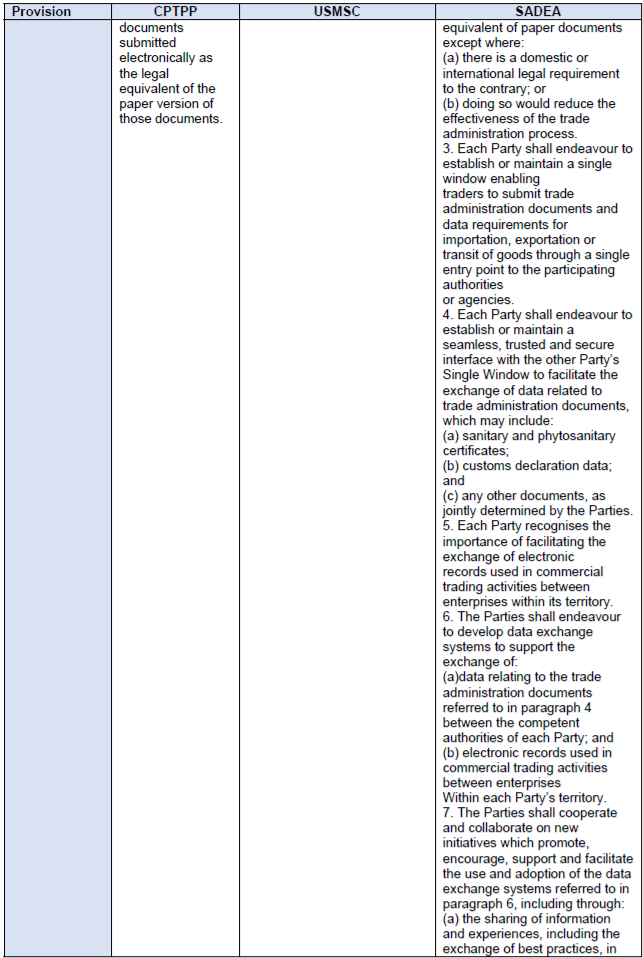

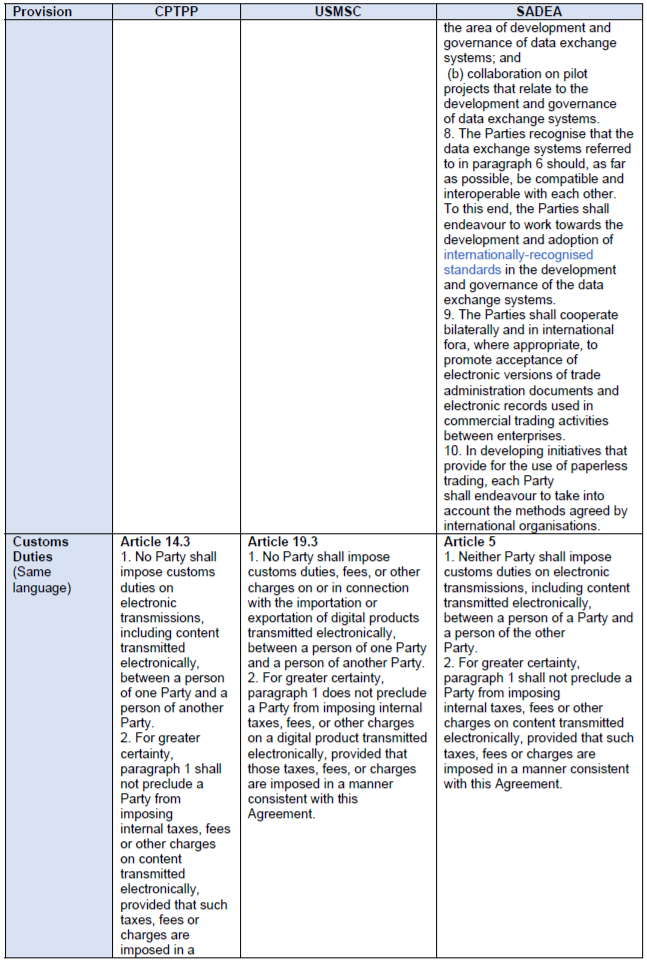

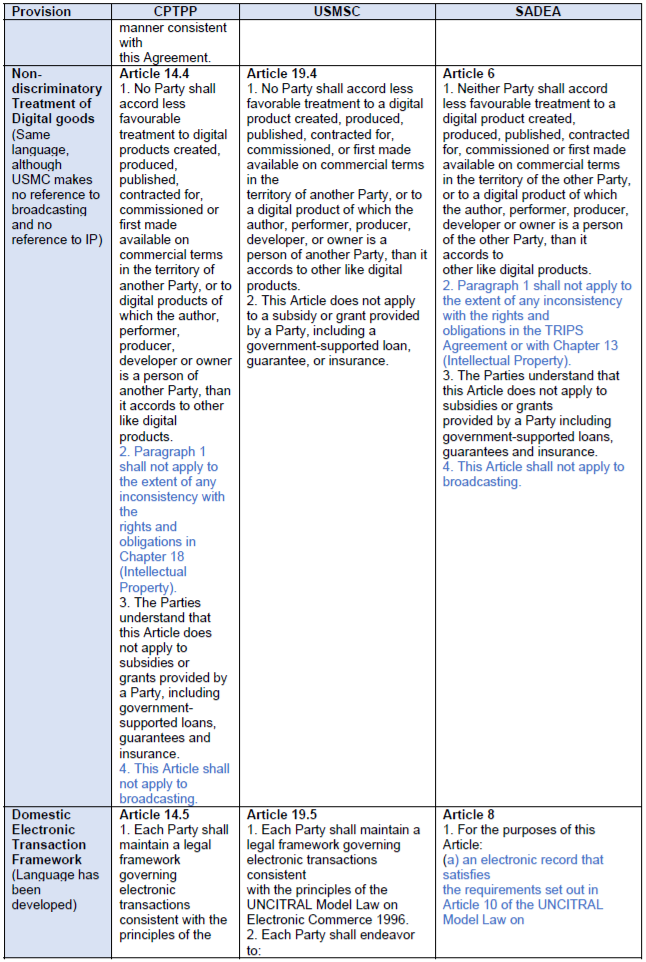

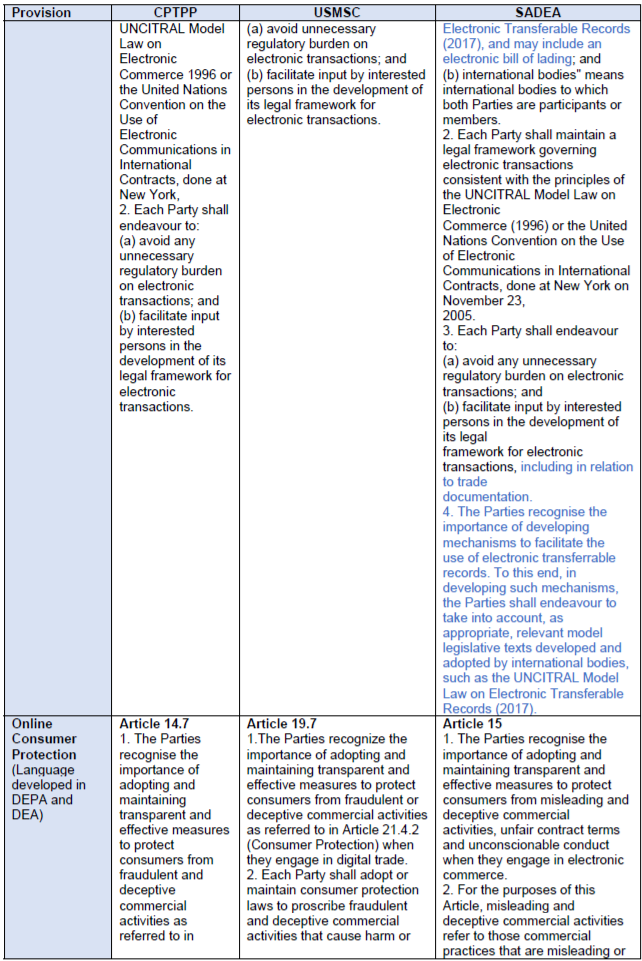

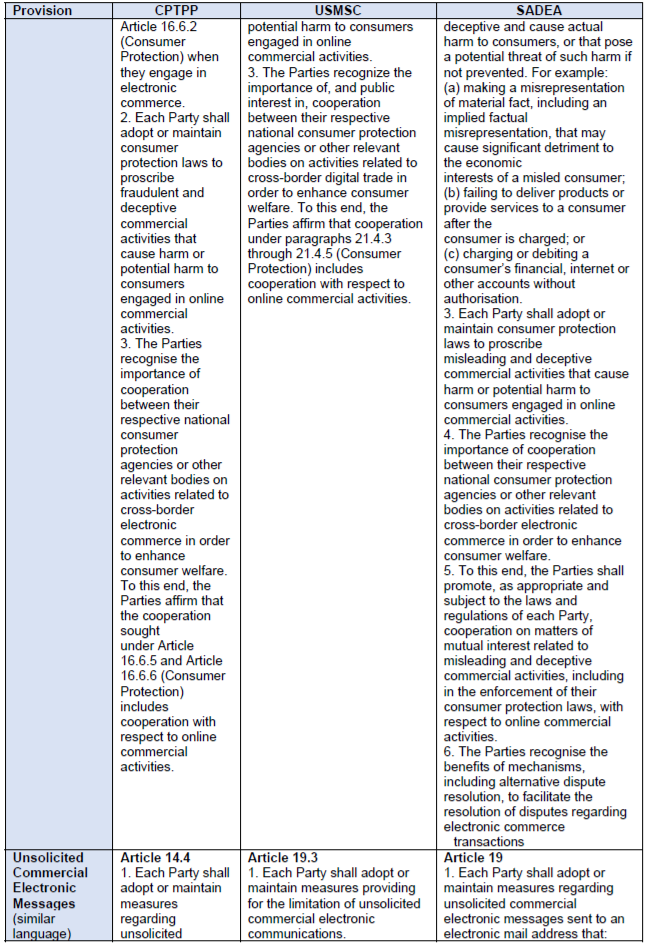

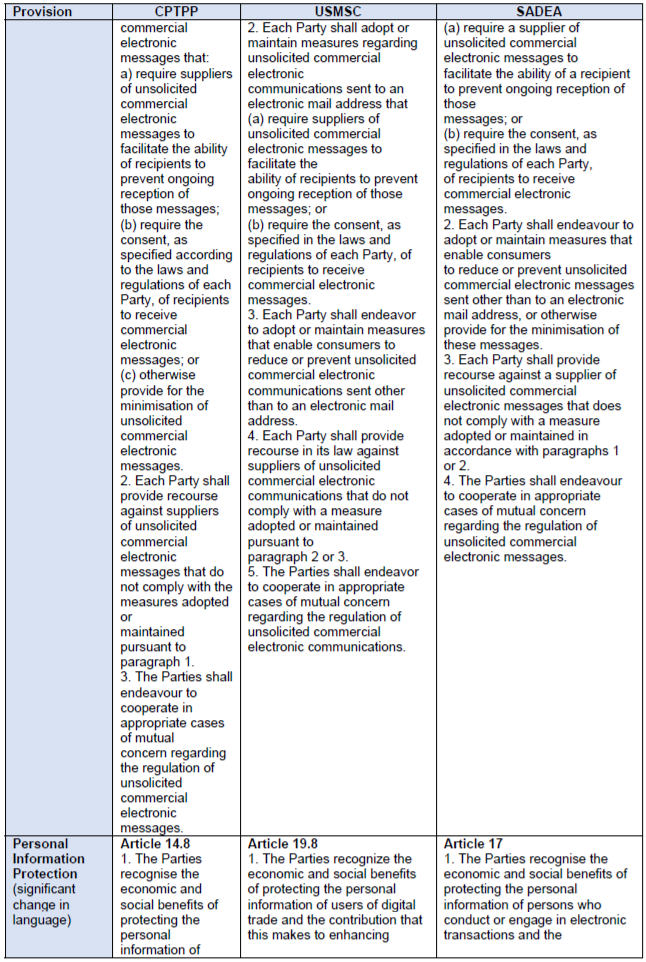

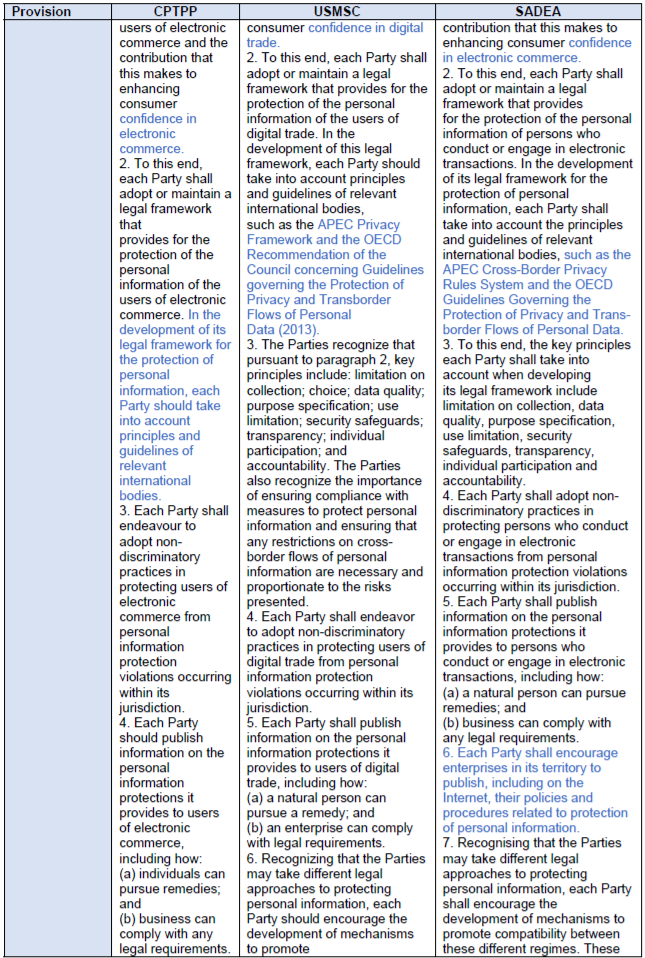

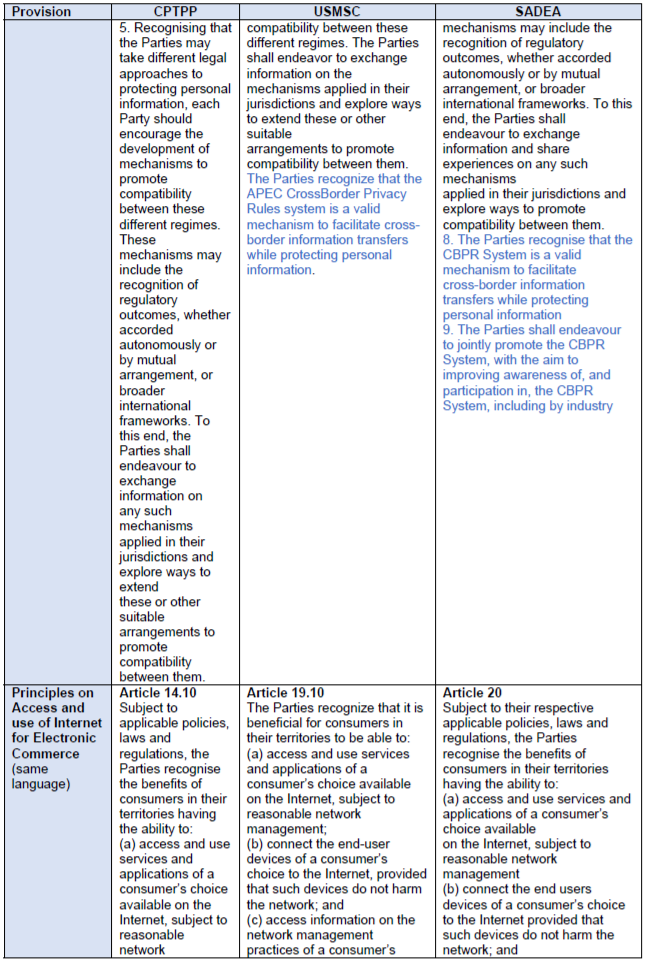

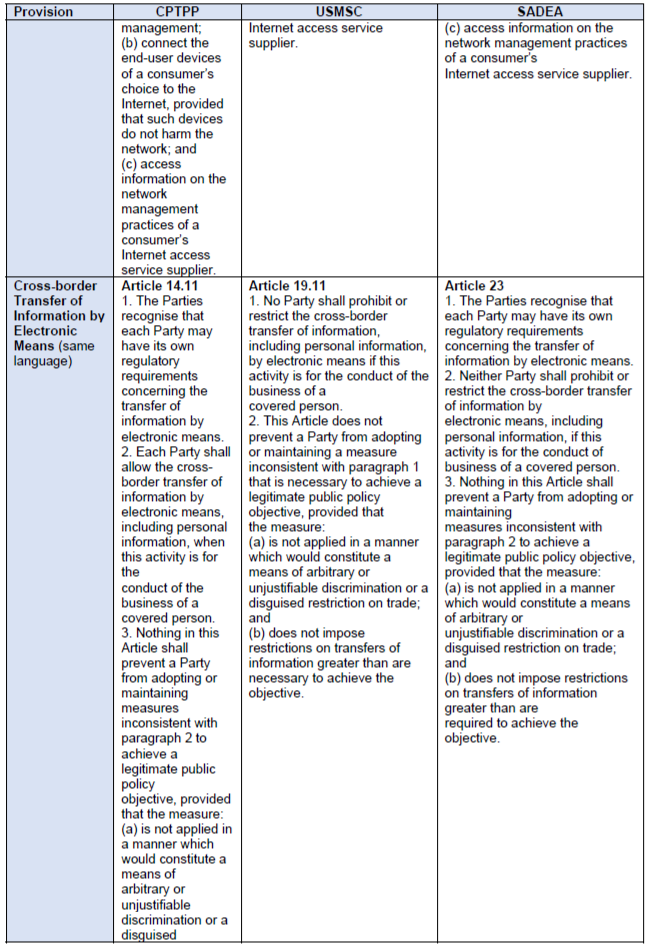

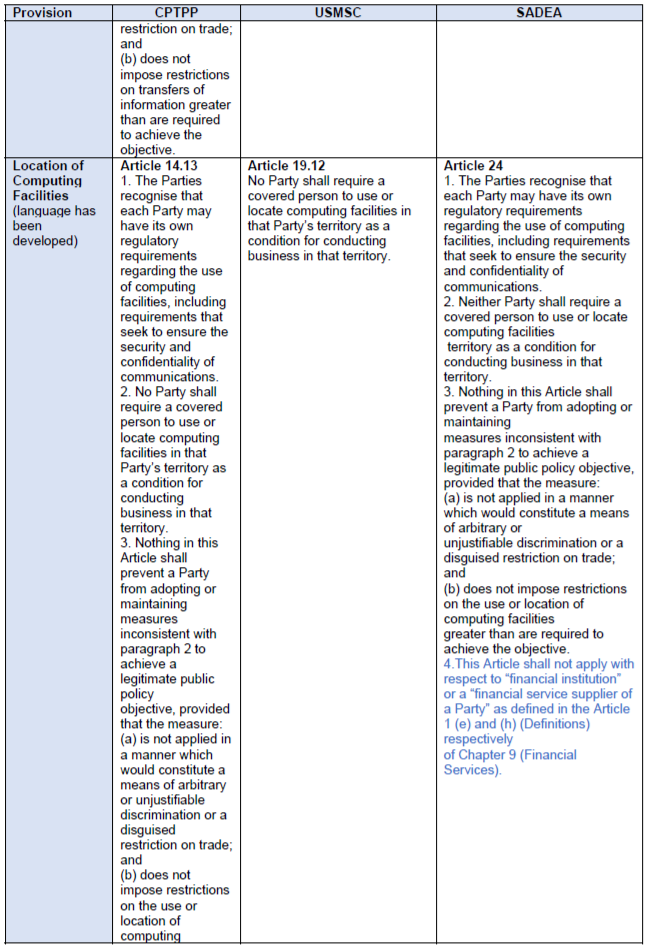

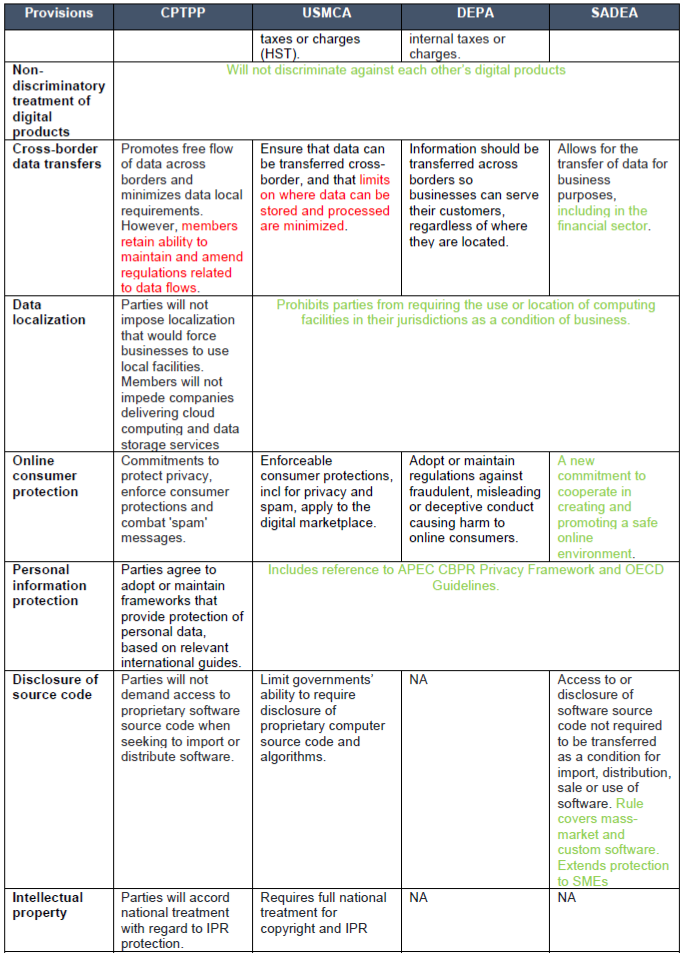

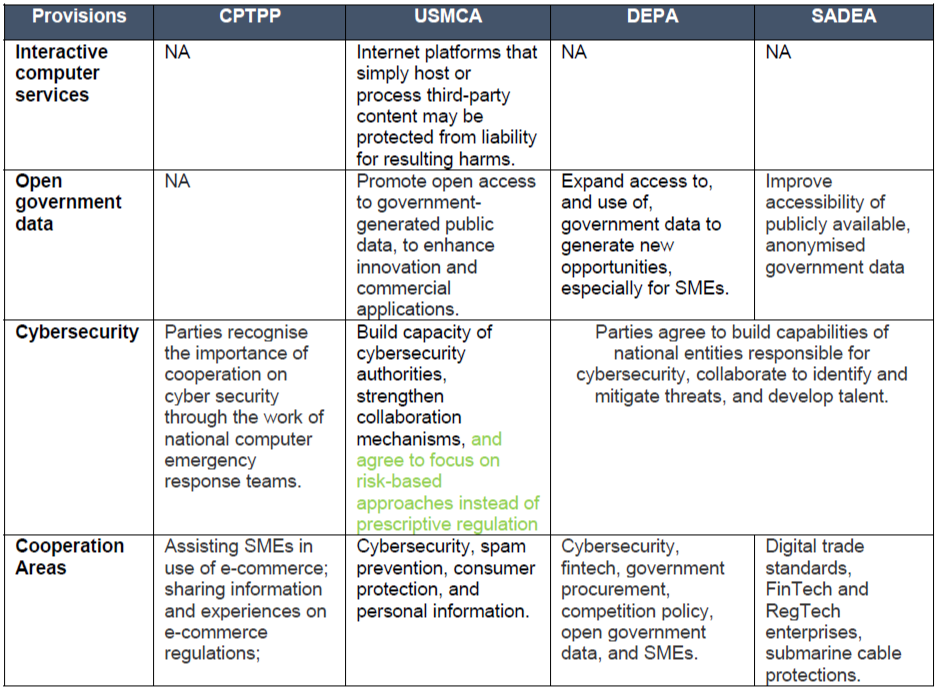

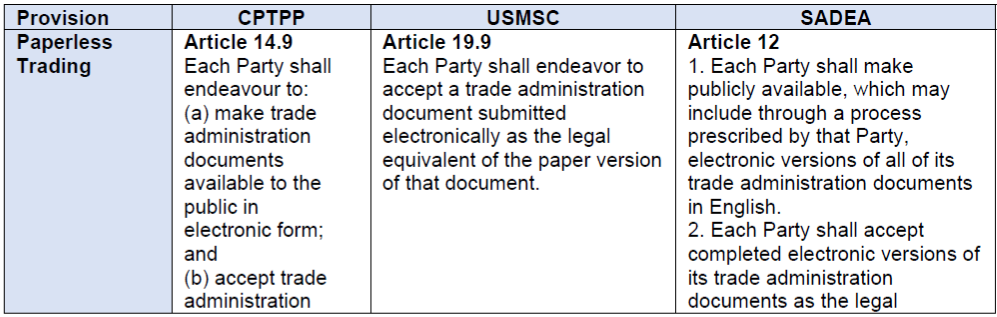

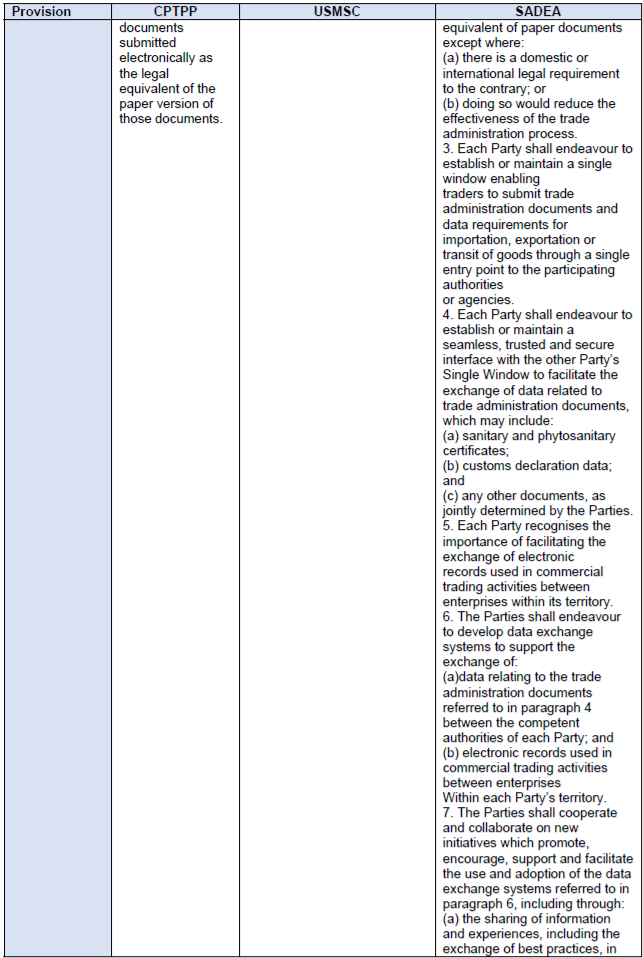

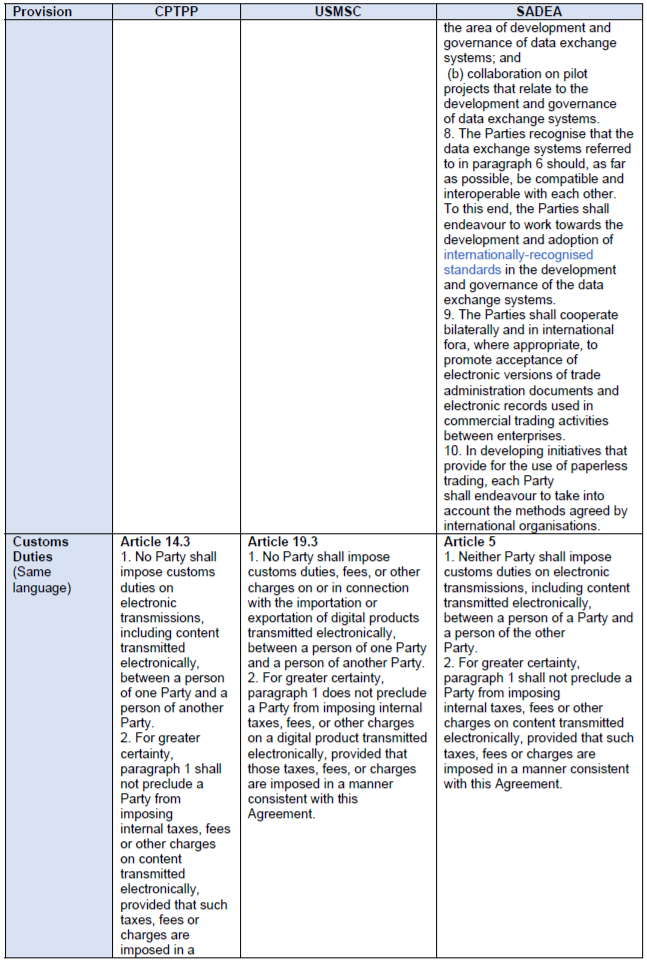

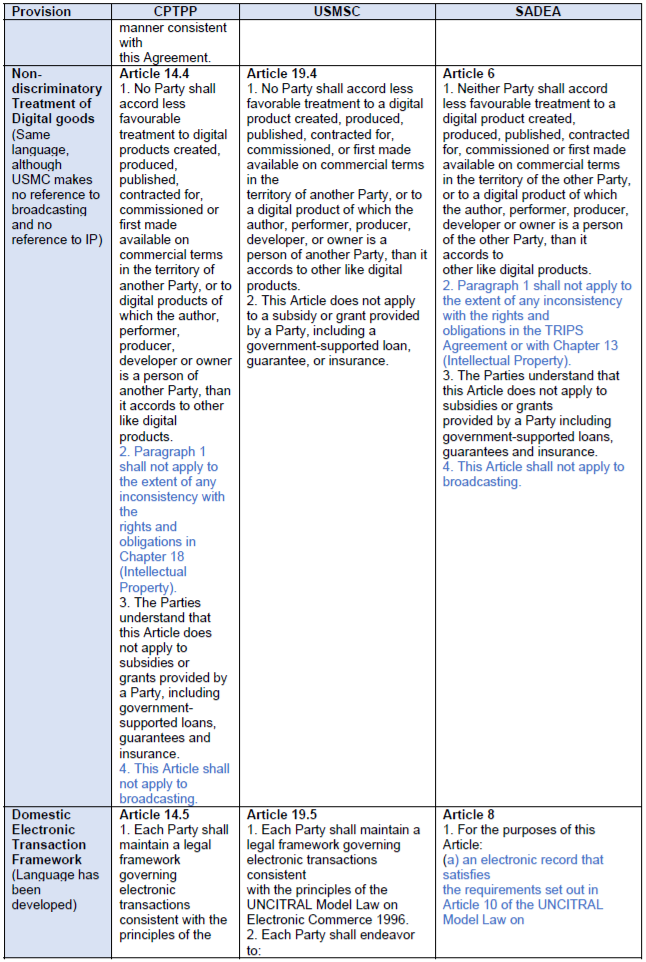

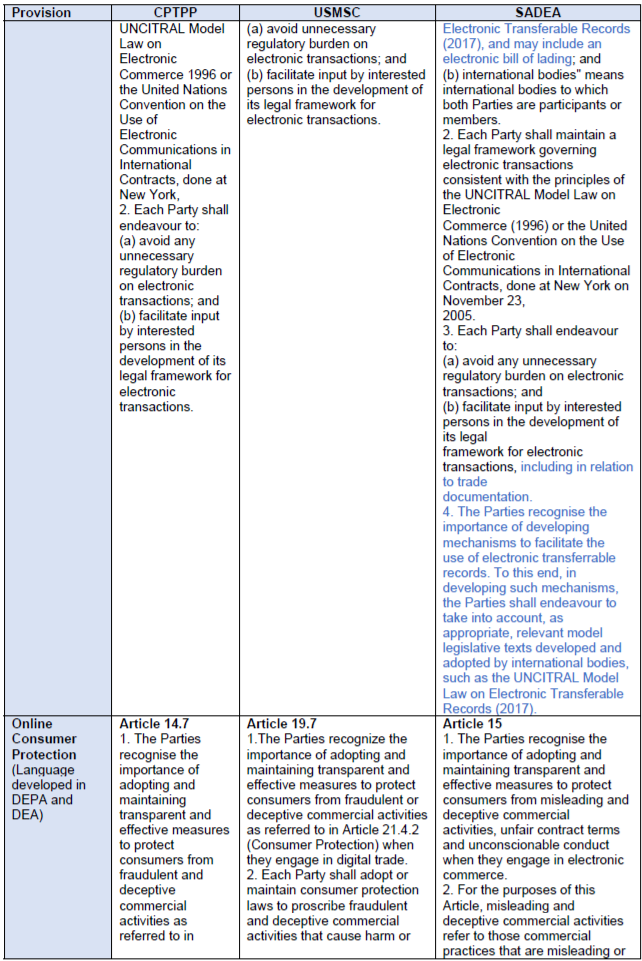

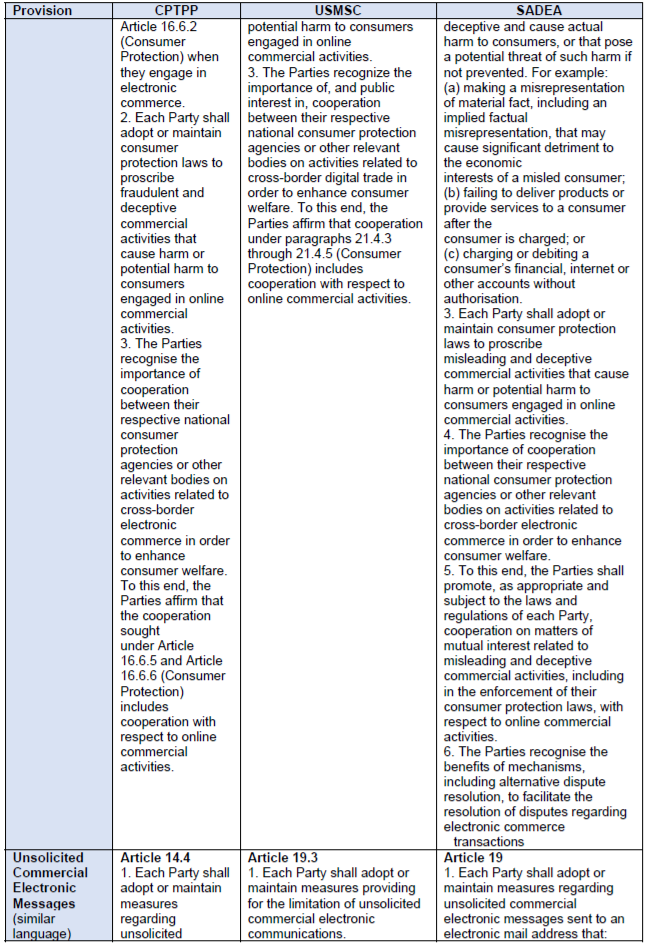

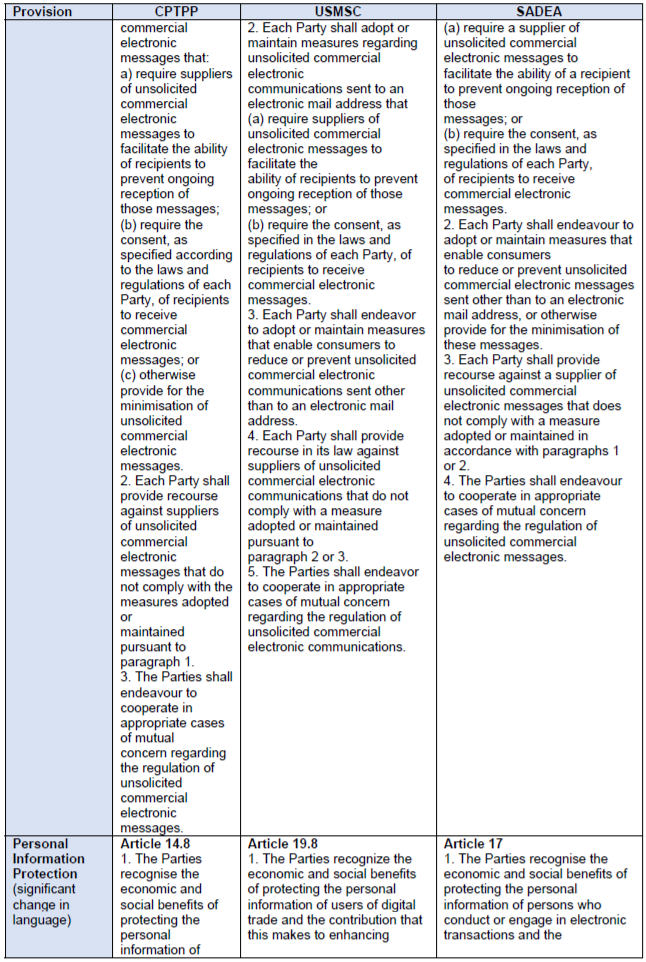

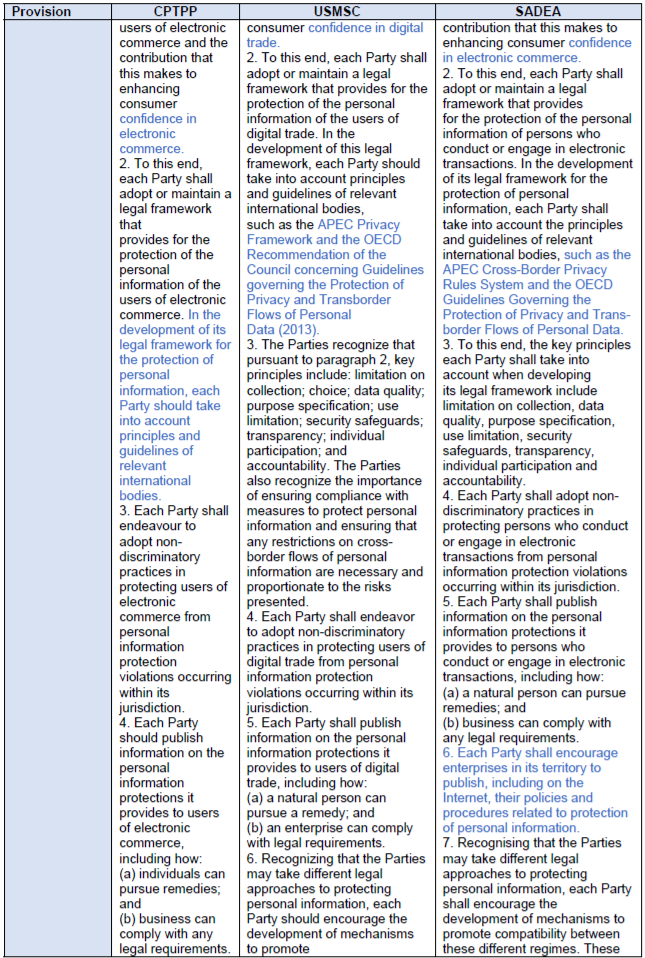

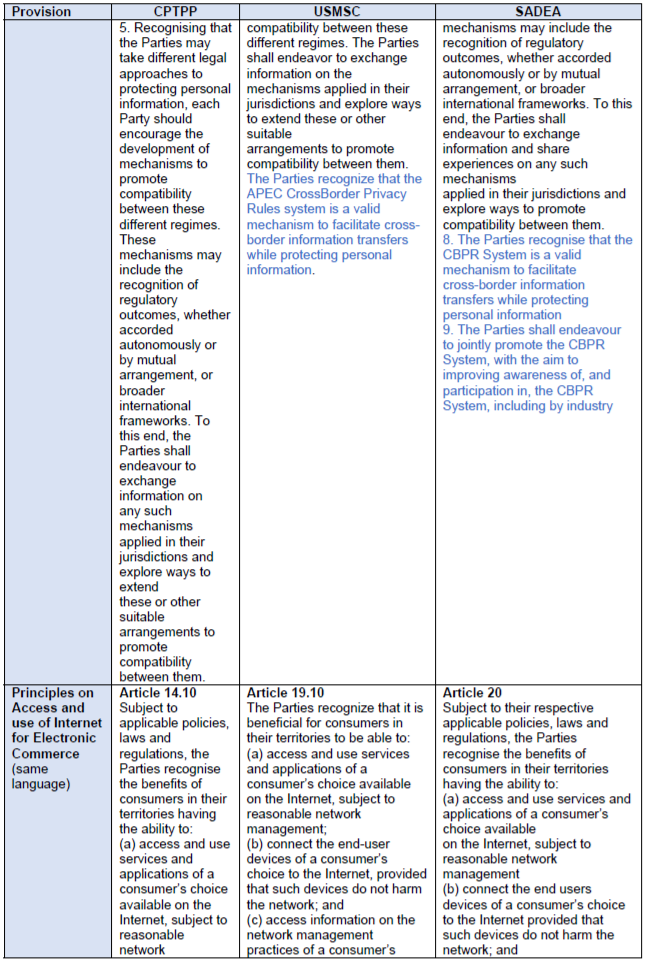

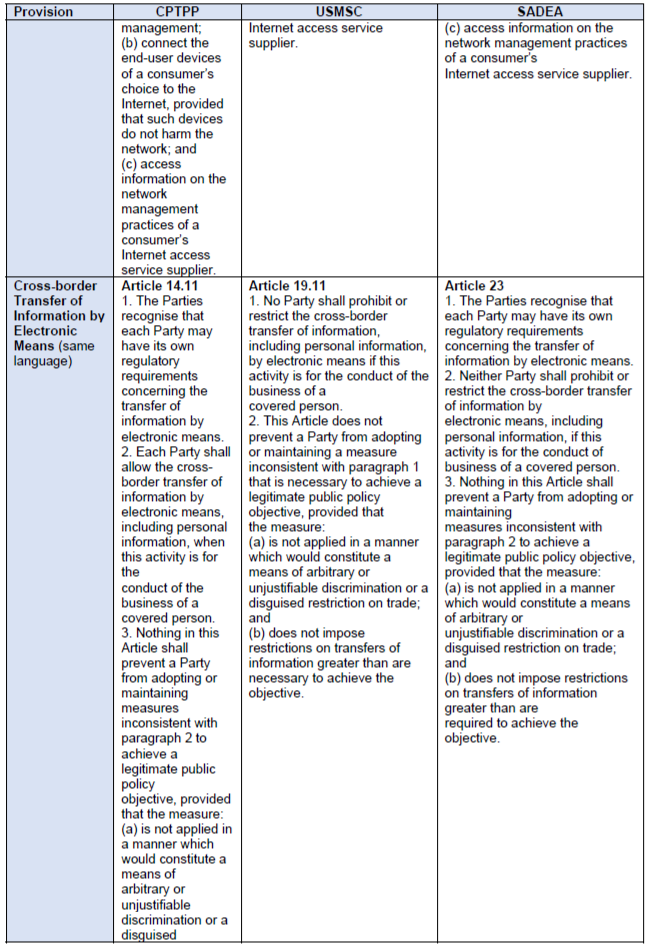

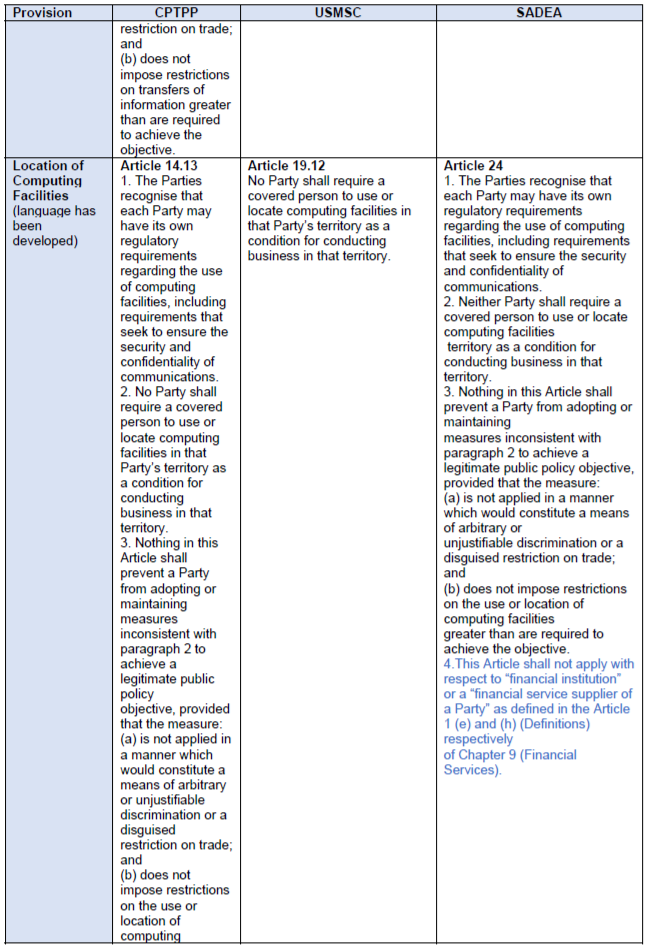

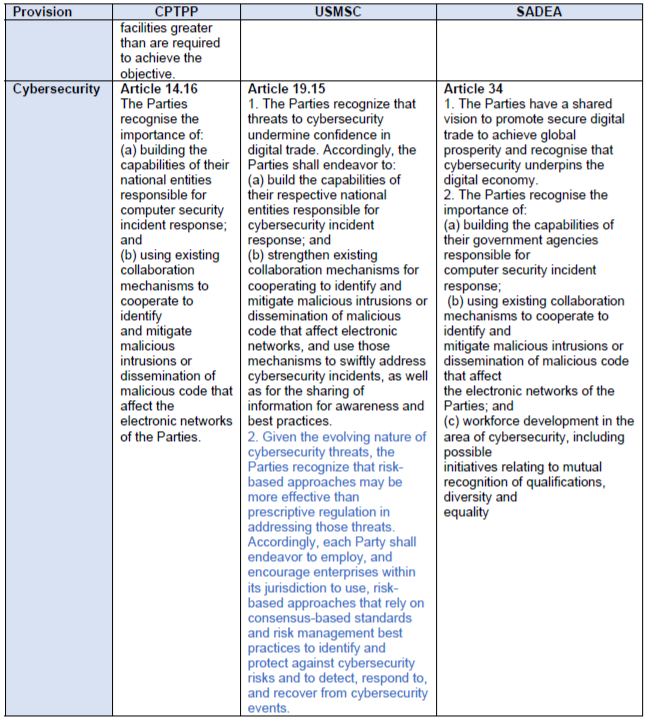

A more detailed rendering of the language being developed in these agreements provides a far more complex picture in terms of the commonality of digital trade language and protections being offered (Table 3).The summary table shows that the three most significant areas where the language has been developed, particularly when the DEPA and SADEA are compared to the earlier CPTPP and USMC, relate to paperless trading, personal information protection and location of computing facilities, with small developments in domestic electronic transaction frameworks, online consumer protection, and cybersecurity.

Table 3: Key and Developing Language Across Digital Trade Agreements

Differences in Digital Trade Language

So, what differences emerge from a textual analysis of the four agreements across key provisions affecting digital trade?

Cross-border Information Transfers and Localization

With minor variations, all four agreements encourage the cross-border flow of information and prohibit localization requirements. On cross-border flows, CPTPP and USMCA replicate language obligating members to allow transfers, but add the exception of allowing the adoption or maintenance of regulatory measures to achieve ‘legitimate public policy objectives’. The CPTPP also first explicitly recognizes respective regulatory requirements of members. DEPA and SADEA follow the same language as the CPTPP.

On localization, the USMCA (like the US-Japan Agreement) clearly prohibits the use or location of computing facilities as a condition for conducting business. The CPTPP prohibits it, but again adds the exception allowing regulatory measures to achieve legitimate public policy objectives. SADEA and DEPA again follow the language of the CPTPP. While these exceptions can be seen to preserve member rights in protecting privacy and security concerns, the vague LPPO language has already been used to create legal uncertainty, being interpreted subjectively, and used for more overtly protectionist purposes.

Future agreements could perhaps instead or in addition include an illustrative list of public policy objectives that provide guidance to all members, allowing sufficient flexibility but also preventing protectionist measures.

Information Transfers in Financial Services

In the trade agreements examined here, there are specific commitments that are intended to protect and promote the flow of information, and prohibit data localization requirements. But these do not always extend to the financial services sector. In this regard, the USMCA stands out distinctively as the high water benchmark, providing detailed provisions on data localization prohibitions in the financial services chapter.57 These provisions state that no member shall make use or location of computing facilities in its territory as the condition for conducting business, so long as financial regulatory authorities have “immediate, direct, complete, and ongoing access to information processed or stored on computing facilities”. This explicit recognition is useful as economies have often justified localization to ensure government access to financial data. The SADEA subsequently replicated the USMCA language.

Having said that, all agreements have still left exemptions and room for domestic regulation in this area. Regarding data flows in financial services, CPTPP’s language is particularly vague.58 DEPA too upholds the economy’s existing commitments under CPTPP to allow data to flow freely and prohibit rules requiring localization but does not extend these to financial services. The agreements also differ on national treatment and market access to digital payment services. While commitments in this regard, under WTO are optional, USMCA applies explicit national treatment to payments and market access to firms from other members. The CPTPP on the other hand has made national treatment optional, thus not guaranteeing nondiscriminatory treatment, and allowing members to give favourable treatment to local e-payment services, if foreign services are also allowed to operate. Additionally, the definition of e-payment services in the CPTPP focuses on credit card networks and business-to-business transactions59 – whereas it is in retail payments (B2C transactions, e-commerce, and disruptive new payments channels) that much of the innovation and action has taken place.

Promotion of Interoperability

Amongst the four agreements reviewed, DEPA contains the most discussion on encouraging interoperability. As part of the agreement, members explicitly recognize the role of international standards in facilitating interoperability between digital systems and enhancing value-added products and services.

While DEPA excludes financial services from many provisions, it has a dedicated chapter on electronic payments. Here the parties have ‘agreed to support the development of efficient, safe and secure cross border electronic payments by fostering the adoption and use of international accepted standards, promoting interoperability and interlinking of payment infrastructure’. SADEA contains similar language, even more specifically calling for both parties to adopt international standards such as ISO20022 60, so as to enable greater interoperability between e-payment systems.

DEPA members also agree to promote the use of APIs, by making them available to third party players. This additional commitment rounds out DEPA’s holistic approach to reducing cross-border payment friction, by considering the full value chain of interconnected payment networks.61 SADEA too uses similar language on facilitating APIs for interoperability, innovation and competition in e-payments.

In DEPA, commitments to interoperability are also included in personal information protection and data exchange systems, as well as digital identities where members will aim for the ‘establishment or maintenance of appropriate frameworks to foster technical interoperability or common standards’. Similarly, there is a lot of emphasis on adoption of interoperable e-invoicing systems. Each member has agreed to ‘base its measures related to e-invoicing on international standards, guidelines or recommendations, where they exist’. Similarly, SADEA’s commitments to facilitate interoperability most prominently in eauthentication, e-invoicing, and data exchange systems. In other agreements, interoperability features in personal information protection in the US-Japan agreement and e-authentication in the CPTPP.

DEPA and SADEA’s approach to encouraging interoperability could serve as a template for broader WTO discussions on e-commerce and digital trade.

Personal Information Protection

All four agreements focus on protection of personal information. CPTPP puts an obligation on members to adopt or maintain a legal framework that provides for the protection of the personal information. However, CPTPP recognizes different legal approaches to protecting personal information and encourages members to develop mechanisms to promote compatibility among different regimes. Like CPTPP, USMCA obligates members to adopt or maintain legal frameworks for protecting personal information, but incorporates additional provisions that make for a more robust framework, based on principles and international guidelines (specifically referencing the APEC Privacy Framework and the 2013 OECD Guidelines

Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data). USMCA also obligates members to ensure that any restriction on cross-border flows of personal information are “necessary and proportionate to the risks presented”.

SADEA contains similar provisions to USMCA. But, in this case, in addition to recognizing APEC CBPR, members agree to “promote it, and encourage participation in the CBPR System, including by industry”. This type of language – which is a significant departure from the more neutral traditional trade language – is likely to be crucial in fostering the success of such initiatives. DEPA contains provisions similar to USMCA and SADEA, but goes one step further with members agreeing to encourage the adoption of data protection trustmarks by businesses, in order to verify conformance to personal data protection standards and best practices. Members also mutually recognize the other members’ trustmarks as a mechanism to facilitate cross-border information transfers. Again, this innovative formalization of emerging transfer mechanisms is a break from past practice and demonstrates a potential way forward that should be embraced.

Provisions that reference international guidelines and recommendations from OECD and APEC as a basis for framing domestic data protection laws will ensure that there is consistency in digital trade frameworks across economies. Similarly, recognising possible data transfer mechanisms such as the CBPR and data protection trustmarks will ease barriers for businesses, increase digital trust and facilitate digital trade integration.

Liability of Intermediary Service Providers

Intermediary service providers are suppliers of interactive computer services. Provisions on this refer to a specific distinction between service providers and their users. They seek to prevent service providers from being legally liable for harms related to information stored, processed, transmitted, distributed or made available by service users. It allows service providers to moderate online content by restricting any harmful or objectionable material.

USMCA specifically highlights liability of intermediary service providers. In exactly the same language they note that that members will ‘not adopt or maintain measures that treat a supplier or user of an interactive computer service as an information content provider in determining liability for harms related to information stored, processed, transmitted, distributed, or made available by the service’.

After the exit of the US, CPTPP members took out this provision around intermediary liability. SADEA and DEPA also do not address intermediary liability.

Source Code

Source code of software, or an algorithm expressed in the source code, is a trade secret and provides competitive advantage to its owner. Provisions that prohibit the requirement of access to the source code or related algorithms are meant to provide security to businesses, and remove trade barriers. Language in the USMCA specifies that members will not ‘require the transfer of, or access to, code of software owned by a person of the other Party, or the transfer of, or access to, an algorithm expressed in that source code as a condition for the import, distribution, sale, or use of that software, or of products containing that software, in its territory’. At the same time, it is noted that this provision will not prevent a regulatory body or judicial authority of a party from requiring the source code of software or an algorithm expressed in the source code to be made available. SADEA contains the same provisions and language.

CPTPP Article 14.17 also prohibits the transfer of, or access to source code of software, as a condition for the import, distribution, sale or use of such software, or of products containing such software, in its territory. In addition, both CPTPP and SADEA include provisions stating that nothing in the agreement should prevent the inclusion or implementation of terms and conditions related to provision of source code in ‘commercially negotiated contracts’, or an economy from requiring modifications of source code to make the software compliant with existing laws or regulations. The CPTPP and SADEA, therefore, leave it to businesses to negotiate source code provisions on a contract by contract basis, but prevent governments

from mandating access to source code.

CPTPP, however, includes an additional provision, limiting the prohibition on source code to only massmarket software or products containing such software and does not include software used for ‘critical infrastructure’. Annex 8-B on technical barriers to trade also states that, with respect to ICT products that use cryptography and are designed for commercial applications, “no Party shall impose or maintain a technical regulation or conformity assessment procedure that requires a manufacturer or supplier of the product, as a condition of the manufacture, sale, distribution, import or use of the product” to provide a private key or other encryption backdoor. This however, does not prevent a party’s law enforcement authorities from requiring service providers that use encryption they control to provide unencrypted communications “pursuant to that Party’s legal procedures”).62

Regarding mass-market software, it is also questionable how much of such software would not run on computers involved in critical infrastructure. For instance, commercial software could end up being used by government employees. This may inadvertently lead to domestic development of software for critical infrastructure, or that might be used in government systems.63 DEPA makes no mention of requiring source code or algorithm expressed in the source code. However, in Module 3, treatment of digital products and related issues, it incorporates CPTPP’s provision for protecting encryption.

What about provisions unique to a particular trade agreement?

- DEA is the only agreement that includes Submarine Telecommunications Cable Systems, Location of Computing Facilities for Financial Services, and RegTech Cooperation.

- It also has a separate provision dedicated to standards64

- DEPA is the only agreement that includes logistics and digital financial inclusion.

- It is also the only agreement that excludes Electronic Authentication and Electronic Signatures and Source Code

- USMCA is the only agreement with an Interactive Computer Services provision.

- This reflects an issue of particular importance to the US.

- CPTPP excludes Open Government Data whereas all three of the other agreements have these provisions – this is an area that has come more rapidly into view since the early discussions around the TPP.

- Notably, none of the agreements give suitable recognition to the next logical development already taking place in this space: data sharing architectures and arrangements.

- Both DEA and and CPTPP include Internet Interconnection Charge Sharing but DEPA and USMSC do not.

New ‘Digital’ Trade Agreements: A Way Forward, A False Start, or A Dead End?

There are three key challenges that are not yet addressed appropriately in any of these digital trade agreements:

1. Jurisdictional application of provisions that are definitionally cross-border, requiring transnational coordination for effective enforcement

- This includes issues of national security and sensitivity, culturally sensitive interpretations and application, and issue of domestic registration and categorization

2. Coordination across domestic agencies of cross-cutting issues

- This one, however, is not unique or new to digital agreements, just broader and more

complex

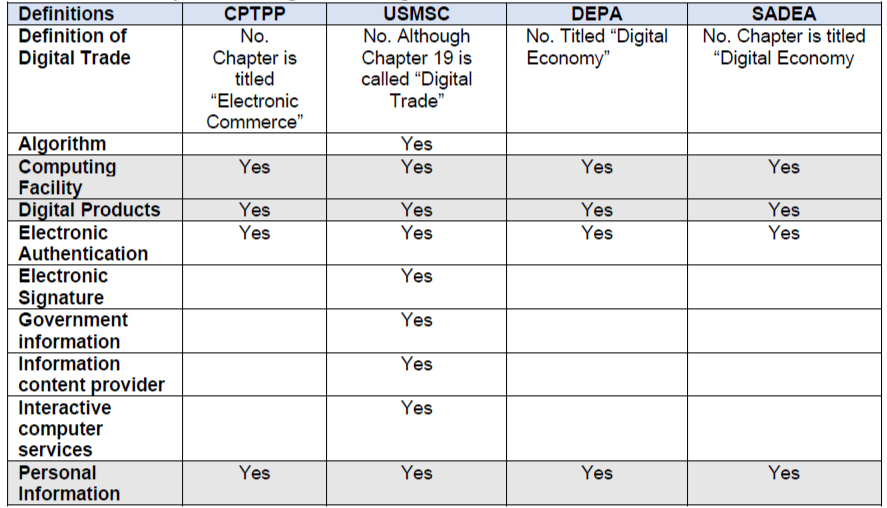

3. Consistent definitions of what ‘digital trade’ actually is, along with definitions of many key digital trade provisions

It remains an open question as to whether the lack of appropriate mechanisms for dealing with these issues are merely early teething problems (similar to those which challenged the initial emergency of services-based trade agreements) or whether they will prove to be the achilles heel of the approach. As regards, the gaps relating to the definitions being used – or not used as the case may be:

- Digital trade: There is no definition of what ‘digital trade’ is, and each agreement uses and refers to different aspects. DEA and DEPA refer to a digital economy agreement; CPTPP refers to Electronic Commerce; while USMC refers to digital trade.

There needs to be needs to be a common understanding and definition of digital trade if it is to become commonly understood and applied.

- Digital services: There is no definition of digital services (only digital goods). Provisions make reference (and recommendation) to “non-discriminatory treatment of digital goods”. But what about digital services?

The definition of digital services is highly relevant for imposing digital taxes, an area where a harmonized approach stands to deliver significant benefits and minimize already existing – and growing – trade frictions.

- Digital identity: There is no definition of digital identities. Even though it is called out for special focus in both DEPA and SADEA.

- Nor of Artificial Intelligence. For effective recognition, promotion and enforcement of protections – let alone consistency with and across future arrangements – this is a very problematic oversight.

There needs to be definitions of umbrella digital technology terms such as AI, 5G, IoT, etc, or these will render themselves moot in relevance and applicability for regulatory coordination.

- Data classification and Platform typologies: There is no recognition of the different types of data, despite recognition of ‘legitimate public policy objectives’ for certain types of data to require special consideration, protection and regulation, including for the purposes of localization. Equally, there is no recognition of the different types of digital platforms even as there are key provisions protecting intermediate liability.

- Limited reference to online platforms, yet a lot of the trade happens via online platforms. The only reference made in SADEA and DEPA “encourage participation by the Parties’ SMEs in platforms that could help SMEs link with international suppliers, buyers and other potential business partners”65

Table 4: Definitional Gaps Across Digital Trade Agreements

Appendix 1: Comparison of Language for Eleven Common Provisions Across the Four Agreements

47 Dr. Peter Lovelock is the Director of the Technology Research Project Corporate (TRPC).

48 Government of Canada, CPTPP, https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accordscommerciaux/agr-acc/tpp-ptp/text-texte/toc-tdm.aspx?lang=eng/agr-acc/tpp-ptp/text-texte/toc-tdm.aspx?lang=eng

49 USTR, USMCA, https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canadaagreement/agreement-between

50 USTR, U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/-japan/Agreement_between_the_United_States_and_Japan_concerning_Digital_Trade.pdf

51 MTI, Digital Economy Partnership Agreement, https://www.mti.gov.sg/Improving-Trade/Digital-Economy-Agreements/The-Digital-Economy-Partnership-Agreement

52 DFAT, Australia-Singapore Digital Trade Agreement, https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/services-and-digitaltrade/Pages/australia-and-singapore-digital-economy-agreement

53 https://www.mti.gov.sg/-/media/MTI/Newsroom/Press-Releases/2018/11/Press-release---The-CPTPP-Enters-Into-Force-in-December.pdf

54 https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/fact-sheets/modernizing

55 https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/07/10/building-on-the-modular-design-of-depa/

56 https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/safta/official-documents/Pages/default

57 USTR, USMCA, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/FTA/USMCA/Text/17-Financial-Services.pdf

58 The financial services chapter includes a section on transfer of information, stating that a financial institution can ‘transfer information in electronic or other form, into and out of its territory, for data processing if such processing is required’. However,its application is left vague, without determining who is a financial institution, nor any mention of regulatory access.

59 WEF (2020) Connecting Digital Economies: Policy Recommendations for Cross-Border Payments

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Connecting_Digital_Economies_2020.pdf

60 Universal Financial Industry Message Scheme

61 WEF (2020) Connecting Digital Economies: Policy Recommendations for Cross-Border Payments

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Connecting_Digital_Economies_2020.pdf

62 HBLR (2019) Cybersecurity and Trade Agreements: The State of the Art, https://www.hblr.org/wpcontent/uploads/sites/18/2019/11/Cybersecurity-Provisions-in-Trade-Agreements_FINAL.pdf

63 HBLR (2019) Cybersecurity and Trade Agreements: The State of the Art, https://www.hblr.org/wpcontent/uploads/sites/18/2019/11/Cybersecurity-Provisions-in-Trade-Agreements_FINAL.pdf

64 DEPA makes reference to open standards in other provisions

65 Article 10.2 of DEPA and Article 36 of DEA

<< Previous