Shiro Armstrong, The Australian National University

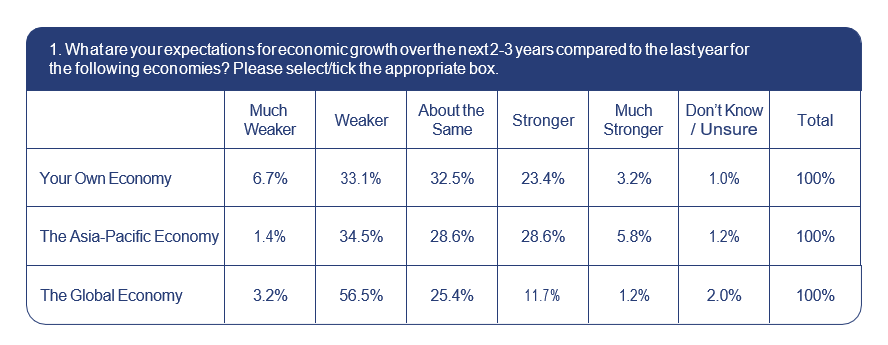

Sharon Zhengyang Sun, University of Calgary

Introduction

This chapter examines how global trade has entered a period of profound disruption and what this means for the future of the international trading system. It argues that recent protectionist trends are not temporary but reflect deeper structural and political shifts, from the unequal distribution of trade gains to the securitization of economic policy. As identified in this chapter, the rise of four major new issues confronting the multilateral system – increased security concerns, supply-chain vulnerabilities, the urgency of climate change mitigation, and digital and AI competition – has heightened the appeal of industrial policies for many economies.

Together with growing digital fragmentation and efforts to harden supply chain resilience, these shifts are reshaping the trade landscape in ways that challenge existing rules.

The chapter is structured in five parts. It begins by outlining the drivers of recent protectionism and the strain on the multilateral system. It then explores new trade issues — security, resilience, the digital economy and industrial policy — before presenting possible models for the trading system’s future. The conclusion highlights three priorities for policymakers: preserve and reform the multilateral system, ensure regional and plurilateral agreements reinforce rather than fragment global rules, and use the green transition as a unifying goal for collective action.

Approaches to trade policy around the world have shifted dramatically over the past decade- and-a-half as short-term disruptions collided with deeper structural changes in the global economy. Trade liberalization delivered prosperity and stability to hundreds of millions of people over the last few decades, but there were two important distributional effects which have had significant implications. Between economies, the global centre of economic gravity shifted from the Western Atlantic to the Pacific with the rise of large emerging economies, especially in Asia—the original BRICS economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) are now larger than the G7 advanced economies in purchasing power — signalling a shift from a unipolar to a multipolar order.2 Within economies, the gains of trade were not adequately distributed, leaving many workers and communities feeling left behind. Together, these two effects have fuelled the steady rise of nationalism, populism and protectionism across the political spectrum in many Western societies, particularly the United States. These forces associate globalization and trade to their stagnant middle-class wages and diminished economic security. In the United States public support for trade and international institutions has been eroding, driving a shift in sentiment inward towards protectionism.

2 As of 2023, BRICS combined GDP PPP was 62 trillion USD compared to 53.6 trillion USD for the G7, according to World Bank data. The example of comparing the economic size of BRICS vs. G7 is commonly used to illustrate the economic gravity shift from ‘west’ to ‘east’. Alternatively, ASEAN plus three could also be used here to demonstrate the global centre of economic gravity shift from Western Atlantic to the Pacific. As of 2023, ASEAN plus three (Japan, Republic of Korea and China) combined GDP PPP was 55.9 trillion USD compared to 53.6 trillion USD for the G7.

These underlying trends were exacerbated by short-term disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which reshaped thinking around supply chains and economic interdependence.

Many economies have retreated from openness, emphasizing national resilience and framing economic security as a sovereign issue to be managed through strengthening domestic capacity and self-reliance rather than global integration.

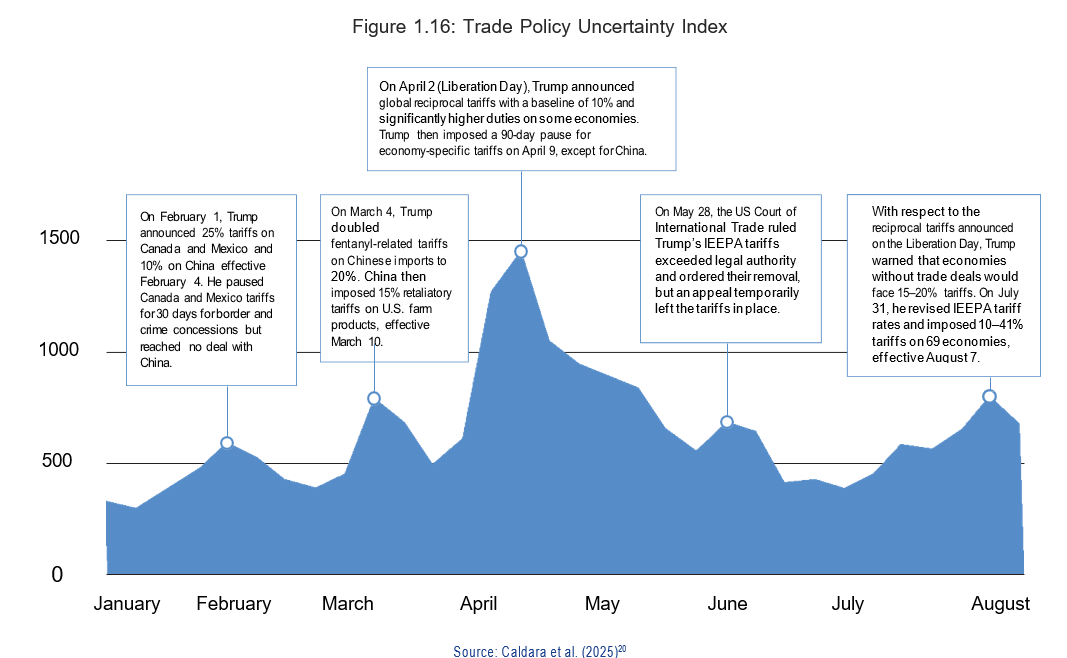

The return of U.S. President Donald Trump added a new layer of uncertainty. In his first term, Trump’s ‘America First’ policy drove a retreat from multilateralism. This was marked by the

U.S. vetoing the appointment of judges to the WTO dispute settlement mechanism, essentially rendering it ineffective, and exploited this situation by appealing adverse WTO rulings into the void. Furthermore, the U.S. also withdrew from the then Trans-Pacific Partnership, now known as the CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership). Under President Joe Biden, the United States cautiously re-engaged with multilateralism while simultaneously maintaining Trump’s tariffs on China and challenging WTO rulings and rules, including through the introduction of substantial industrial subsidies for green and critical technologies. In Trump’s second presidency, economic measures have moved beyond economic protectionism and are explicitly being wielded as instruments to extract economic and non-economic concessions. Tariffs have been imposed globally, with extra penalties imposed for large bilateral goods trade deficits and at times for non-economic frictions unrelated to trade. This transformation has created a fluid landscape of negotiations and heightened uncertainty over the future of the trading system.

This chapter analyzes lessons from the protectionist shift in trade policy, examines emerging issues like digital trade fragmentation and economic security, and outlines possible pathways for a future trade system. The Asia-Pacific has a critical role in averting global trade disorder through stronger regional integration such as CPTPP, RCEP, and APEC, to renew, reform and reinvigorate multilateral cooperation under the WTO and leverage trade cooperation to support innovative industries.

Trade Under Strain

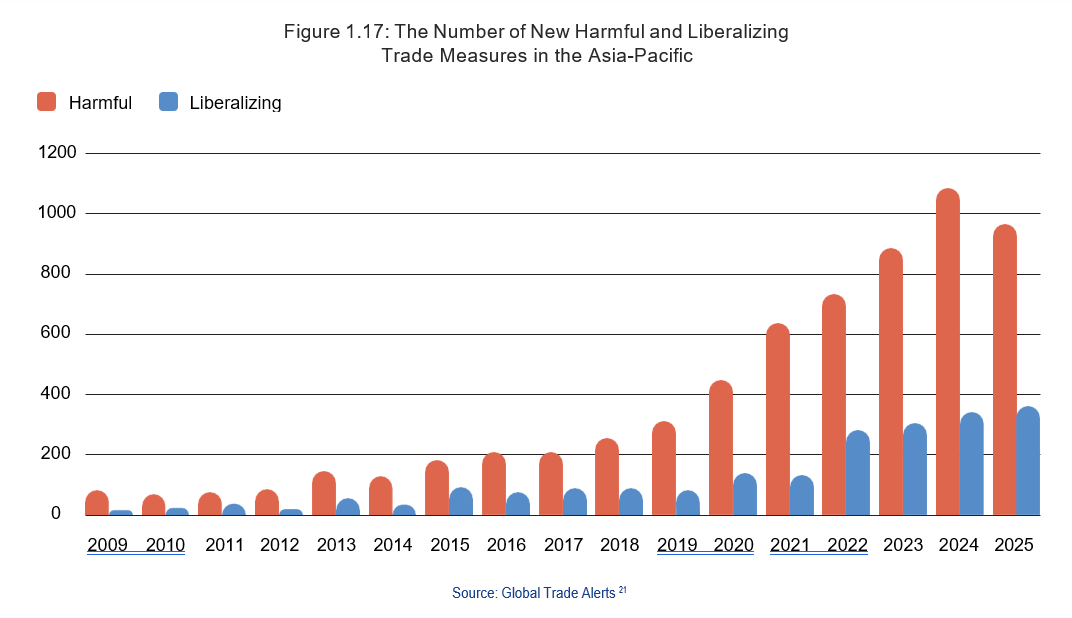

The drivers of recent protectionism can be traced to a series of economic and political shocks, which provided the pretext for economies to turn inward. According to the IMF, the number of new trade restrictions have more than tripled since 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic was one catalyst in this new wave of protectionism. Governments imposed export restrictions on medical supplies and personal protective equipment as they prioritised domestic needs, contributing to the narrative that global supply chains were vulnerable and encouraging calls for greater self-sufficiency. The pandemic also exposed the degree of reliance on Asian manufacturing, sharpening concerns over geopolitical risk and spurring a revival of competitive industrial. Russia-Ukraine conflict and its consequences added another layer of disruption, throwing global fertilizer, food and energy markets — particularly for wheat, grains and natural gas — into turmoil. The conflict in Ukraine also further entrenched the notion that economic interdependence was a cause of weakness, reversing the long-standing logic of integration as a stabilizing force. Collectively, these crises allowed measures such as blanket tariffs, export bans and industrial policies to return to the policy mainstream.

In earlier years, under the US-led multilateral order, the conduct of trade policy could to some extent be pursued separately from national security considerations. The GATT, and later WTO, frameworks allowed economies to trade under agreed multilateral rules that largely insulated commerce from geopolitics but also allowed economies to take measures for national security within the system (GATT XXI). Such measures, however, were exceptions rather than the norm. In this way, trade policy was largely insulated from – though not entirely separate from - economic security policy.

But that was while the rules could keep pace with developments in trade. In some ways, the postwar economic order has become a victim of its own success. China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 was a watershed moment for the global trading system and helped it become the world’s largest trading nation and second-largest economy within a decade. While China is committed to undertaking reforms to ensure its economy became WTO compatible, the pace of progress in some sensitive areas, notably in the role of state-owned enterprises and the relationship between the state and the market, has been a topic of discussion among other WTO members. China’s growing weight in the global economy, together with its reliance on an investment-led rather than consumer-led growth model, has generated spillovers. These spillovers have led to discussions among some economies, particularly regarding issues such as industrial subsidies, potential overproduction and export prices.

3 Gita Gopinath ‘Geopolitics and its Impact on Global Trade and the Dollar’ (Speech, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, 7 May 2024).

4 See Richard N Cooper, ‘Trade Policy is Foreign Is Foreign Policy’ [1972–73] (9) Foreign Policy 18; Richard N Cooper, ‘Economic Interdependence and Foreign Policy in the Seventies’ (1972) 24(2) World Politics 159.

The WTO’s Doha Development Round, launched in 2001, failed to conclude, and rulemaking in areas such as e-commerce and digital trade, intellectual property protections, labor and environmental standards, investment protections, and broader trade liberalization advanced mainly through bilateral, regional and plurilateral agreements. The result is a patchwork of overlapping rules that leave significant gaps in trade governance and contribute to economic fragmentation.

Perhaps the greatest direct threat to the multilateral trading system has come from the new protectionism in the United States. Even before recent shocks, a domestic backlash against free trade had taken root, shaped in part by widening inequality and regional disparities, with disruptions from technological change often attributed to trade and amplified by perceptions of communities being left behind. Although trade generates aggregate gains, the adjustment costs were uneven, and many advanced economies struggled to provide effective support for displaced workers. These gaps in adjustment mechanisms contributed to political discontent, though other forces – notably immigration, technological disruptions and cultural anxieties – also played a critical role.

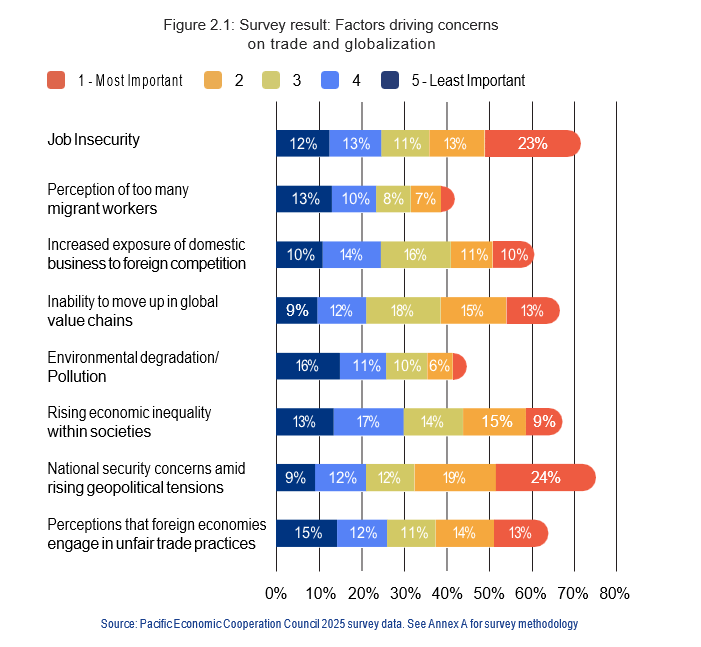

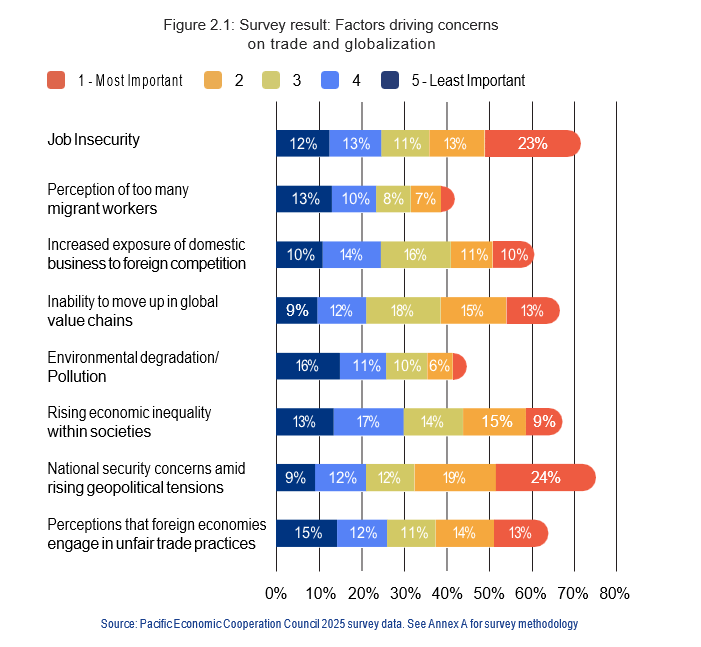

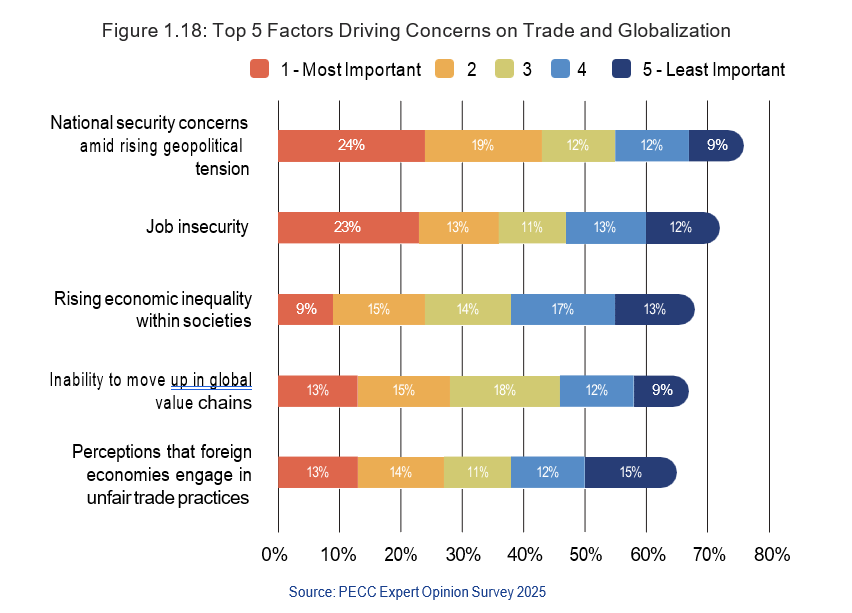

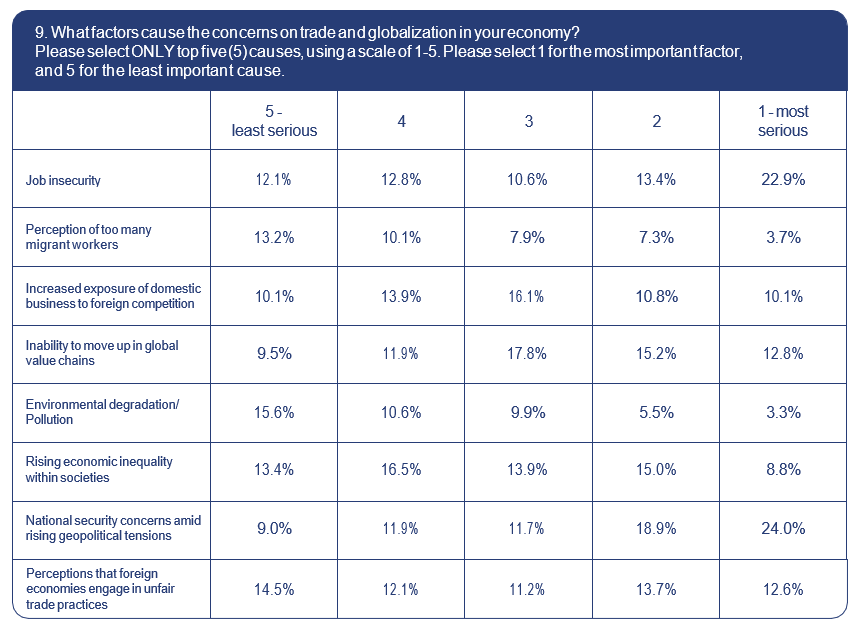

Figure 2.1 summarizes PECC’s opinion survey results of 504 responses on the factors driving today’s concerns on trade and globalization from academics, think tanks, businesses, government, media and civil society across APEC economies. The results show job insecurity and national security concerns amid rising geopolitical tensions are among the most important factors that cause concerns on trade and globalization in one’s economy. This is followed by the perception that one’s economy is unable to move up in the global value chain and that foreign economies engage in unfair trade practices.

Furthermore, the lack of cooperation in the multilateral system has magnified today’s trade tensions. The erosion of stability means that predictable rules are being replaced by market access contingent on politics. This reallocates capital from efficient frontiers to politically robust but higher-cost locations.5 It can be tempting for economies to think that this might be advantageous because protection may make their products look relatively more attractive in domestic markets. But when decisions are no longer grounded in market fundamentals, outcomes become unpredictable. The erosion of norms also begets more unilateralism. Once major economies normalise derogations, others will inevitably follow. Coordination is always difficult, but today’s multilateral system is especially vulnerable because existing rules do not adequately cover many of the issues now at the forefront of trade politics, such as industrial subsidies, digital trade, data governance, climate measures and security-driven controls. With the WTO’s enforcement mechanism paralyzed, except for the plurilateral Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) workaround, these gaps invite unilateral fixes that cannot be arbitrated, further undermining the system.

5 Tatsushi Okuda and Tomohiro Tsuruga, ‘Geoeconomic Fragmentation and International Diversification Benefits’ (Working Paper No 24/48, International Monetary Fund, March 2024).

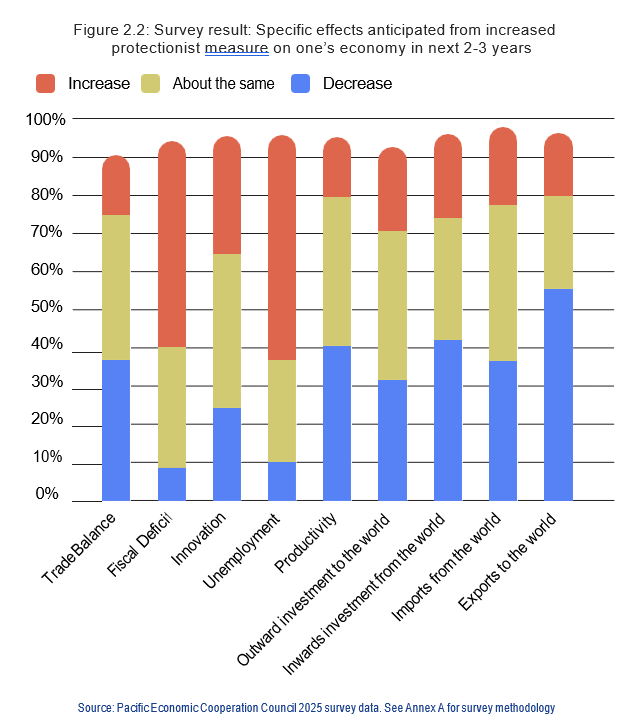

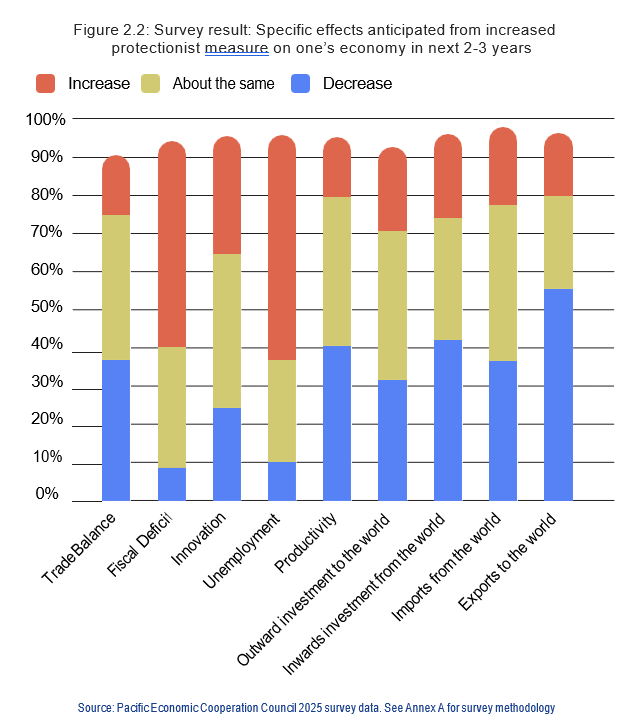

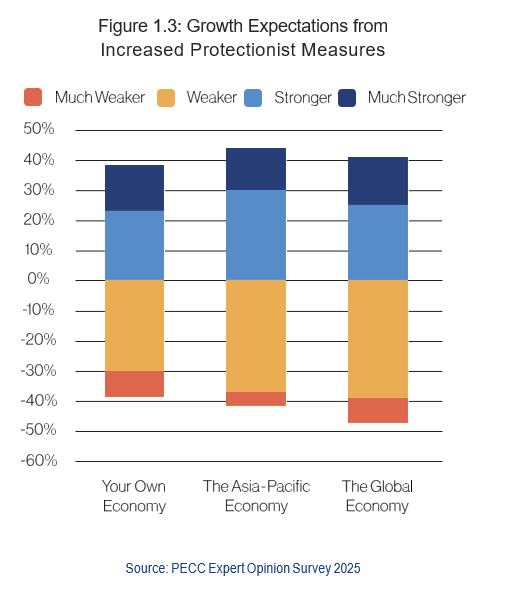

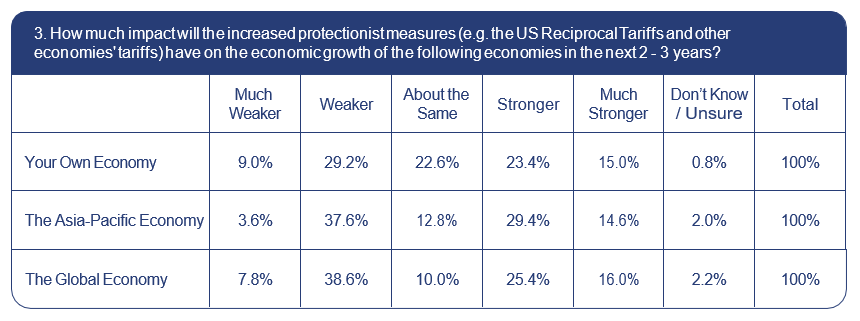

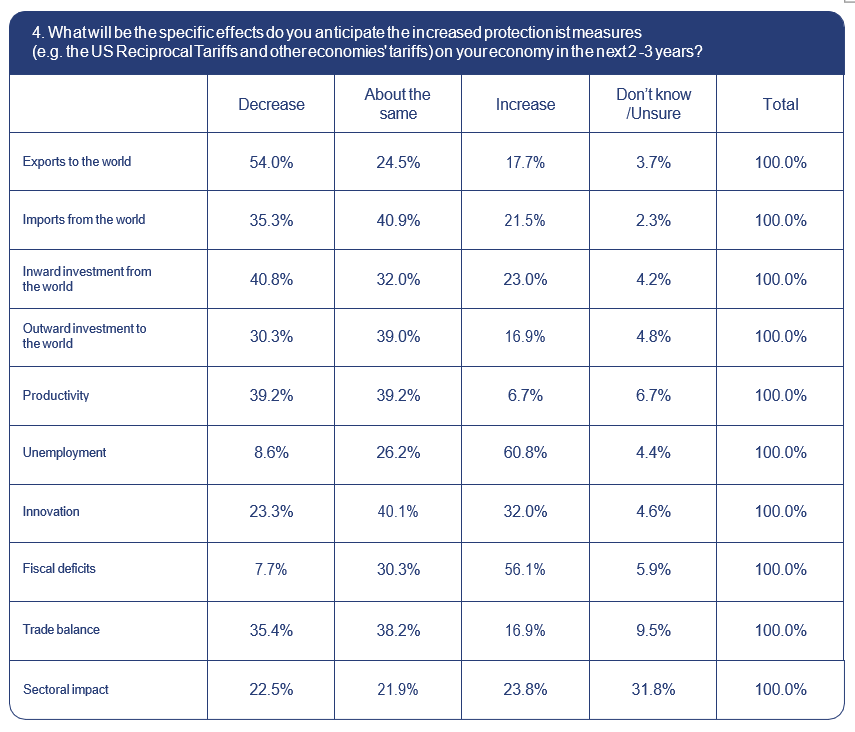

Figure 2.2. shows PECC’s survey results on the specific effects anticipated from the increased protectionist measures on one’s economy in the next two to three years. Anticipated effects show that increased protectionist measures will likely increase unemployment, increase fiscal deficits, decrease global export, and decrease outward investment to the world.

It now seems as though we’re moving to a new world, but what that will look like is still unclear. The digital economy, economic security concerns and climate imperatives represent new technical and regulatory challenges, while older structural issues such as distribution of the gains from trade and the creation or strengthening of social safety nets remain unresolved. To prevent disorder from sliding into conflict and reversing eight decades of growing prosperity, a set of principles and frameworks is essential. The fundamental logic of productivity gains from trade and multilateral cooperation still hold, as does the role of economic interdependence in building peace and prosperity by intertwining national interests and constraining conflict. But the political reality is that the backlash against globalization and growing security concerns is driving a shift in policy inward. The challenge is to rebuild trust in open and predictable rules- based trade while adapting institutions to new realities. That requires constructing a renewed social license for open trade, acknowledging that while globalisation and trade had issues, a lurch to protectionism and economic nationalism would leave everyone worse off.

New issues in global trade

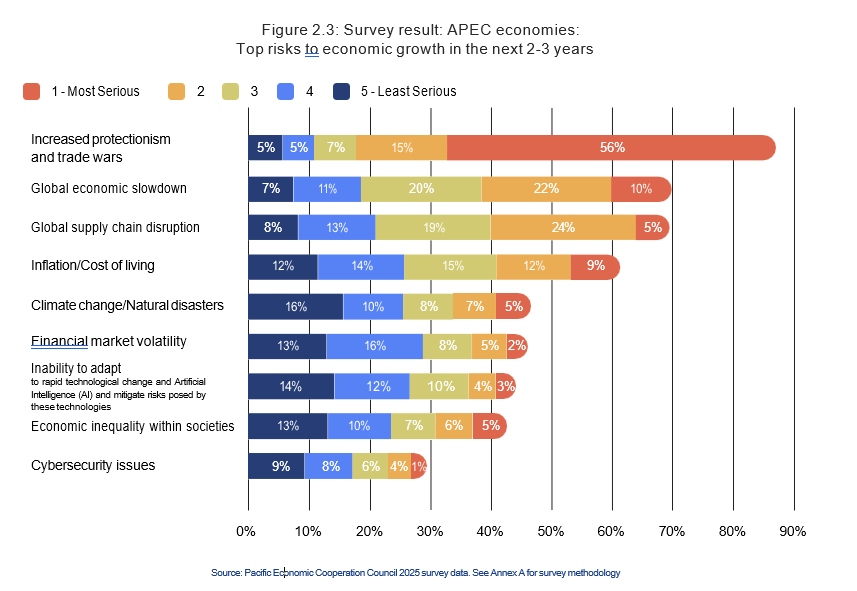

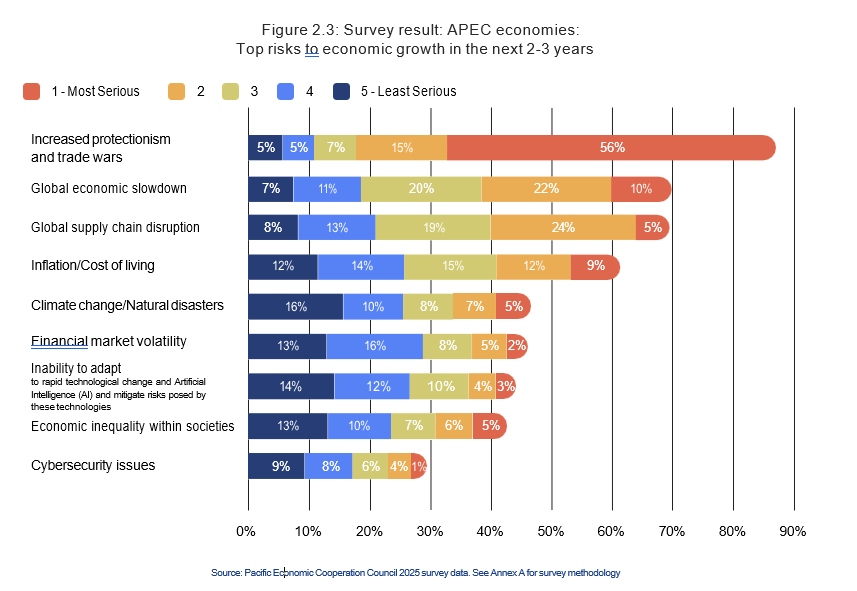

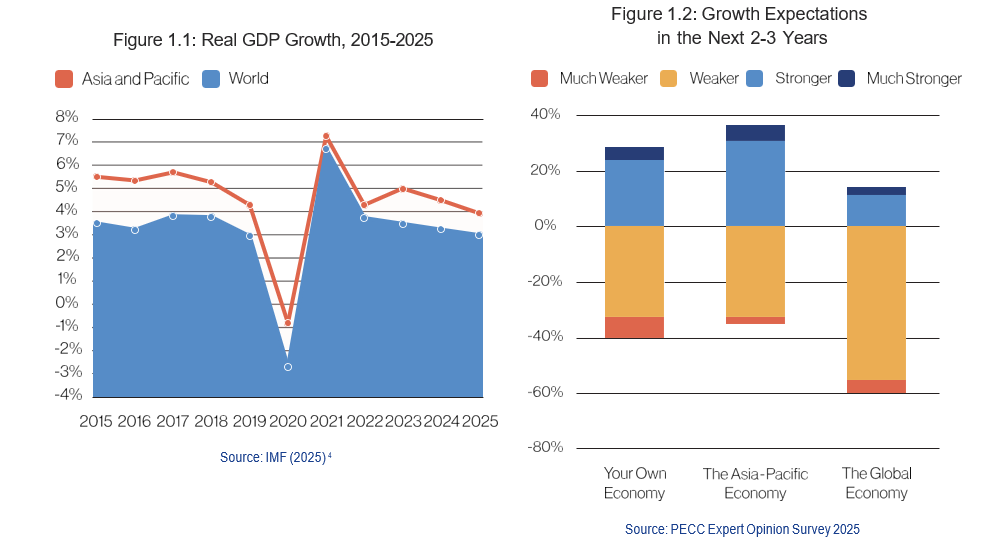

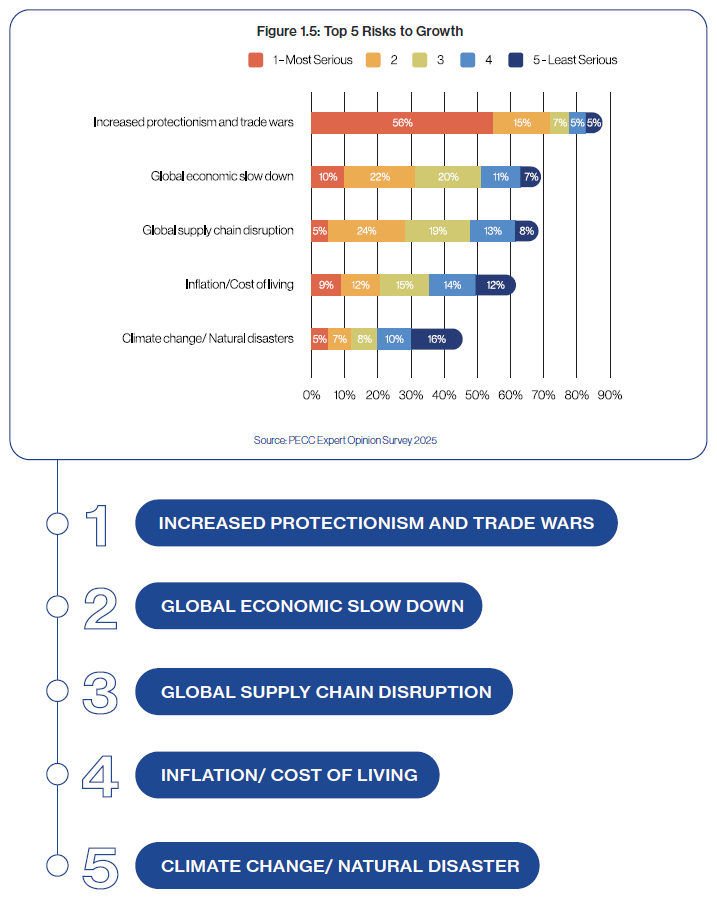

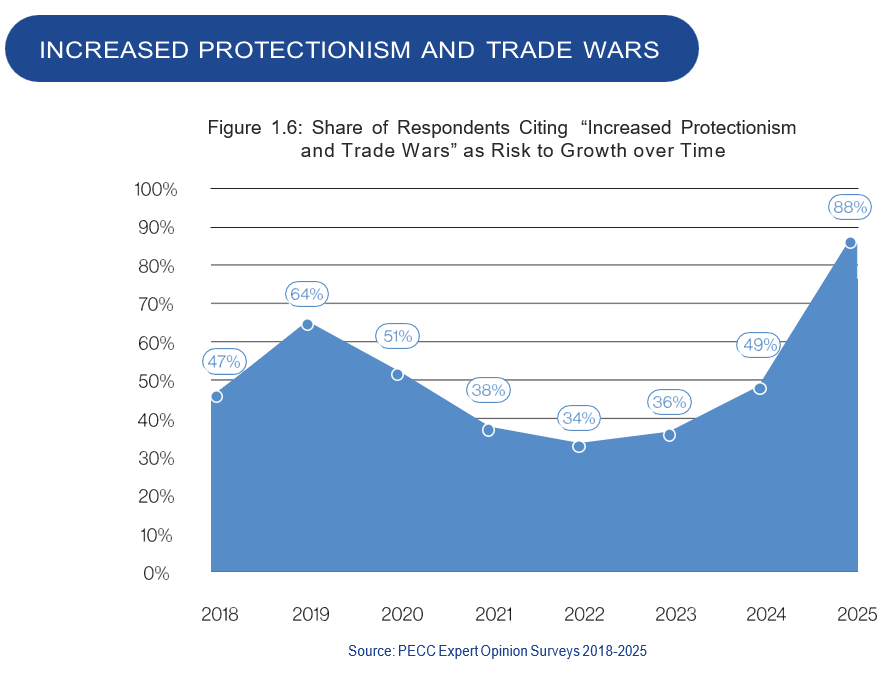

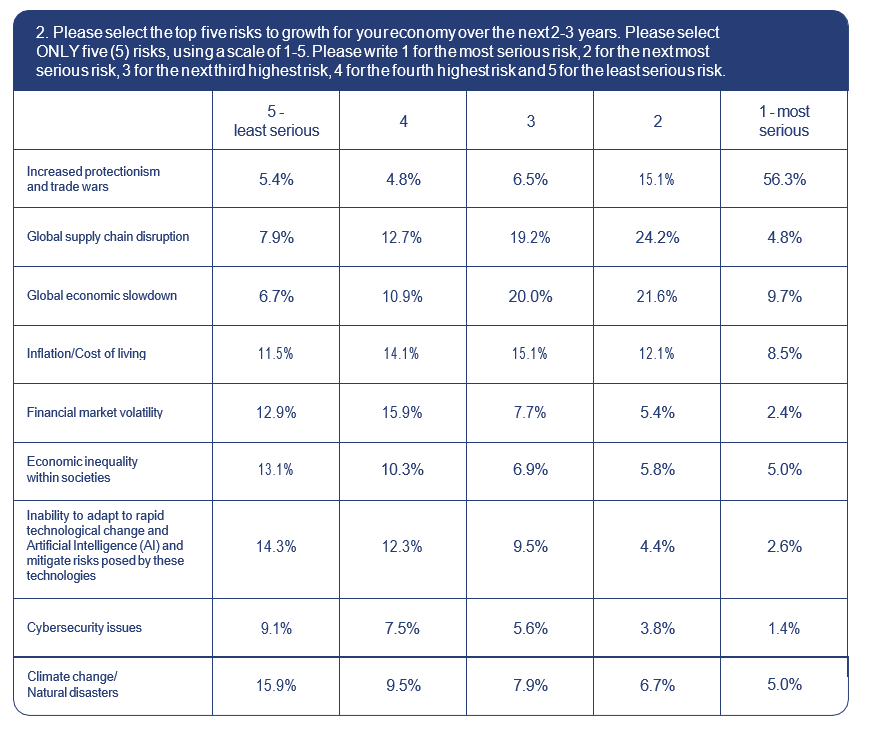

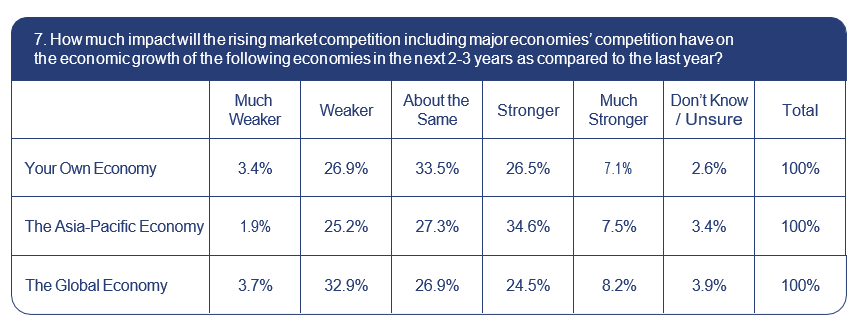

The top risk to economic growth in the next 2 to 3 years identified by PECC survey respondents was protectionism and trade wars (Figure 2.3). But even as the world grapples with the legacy of recent shocks, the global trade landscape is being reshaped by new issues.

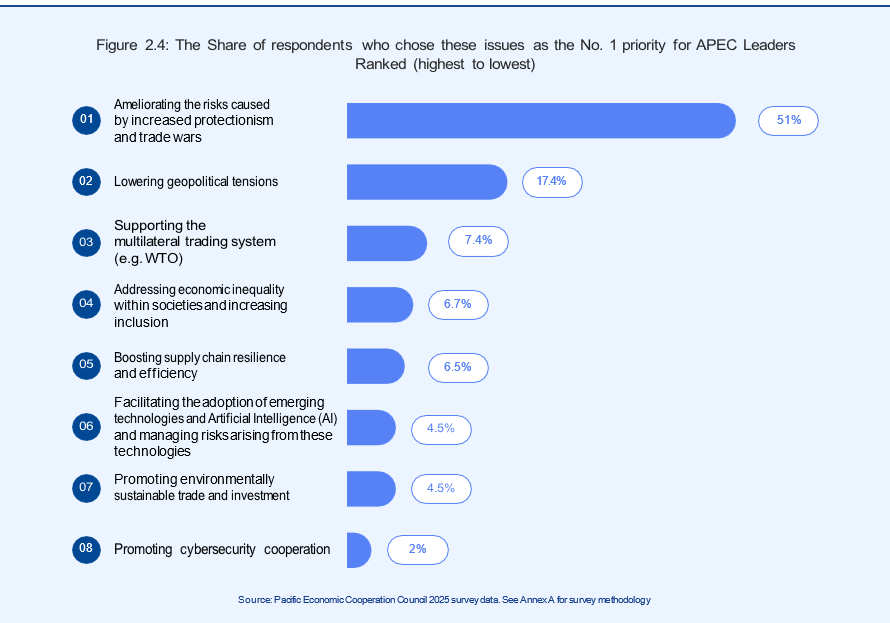

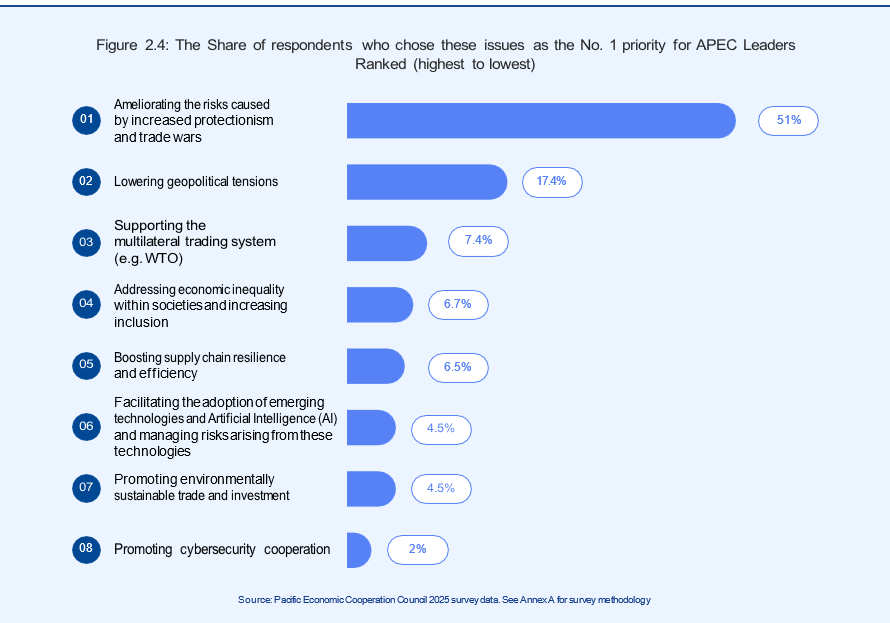

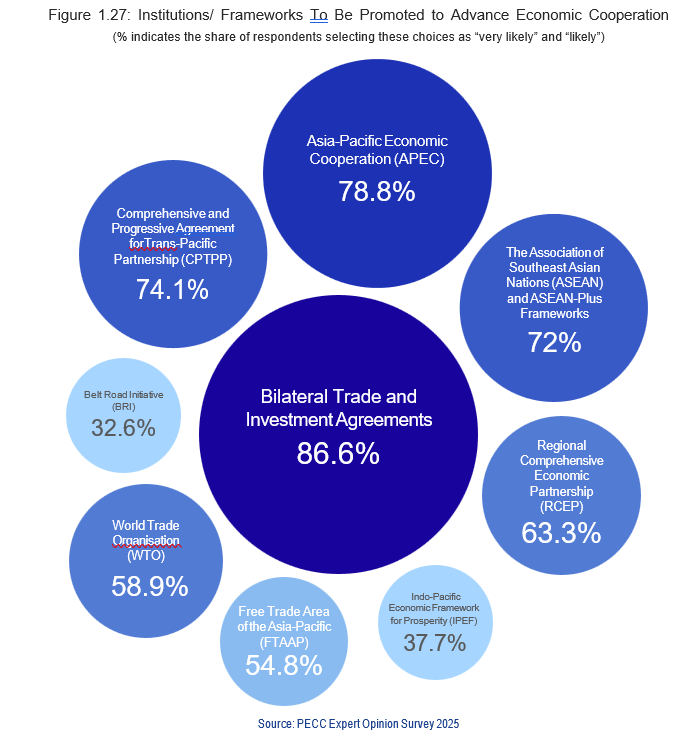

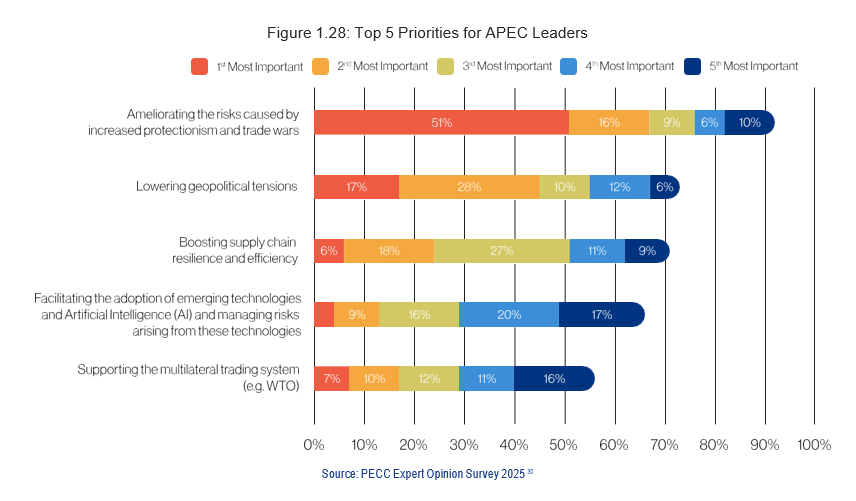

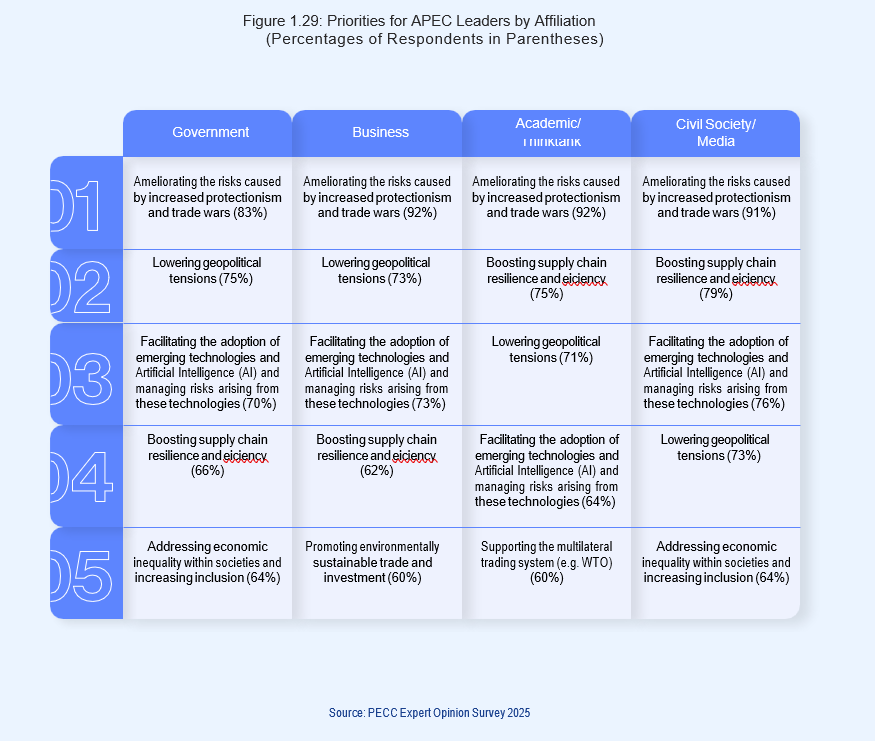

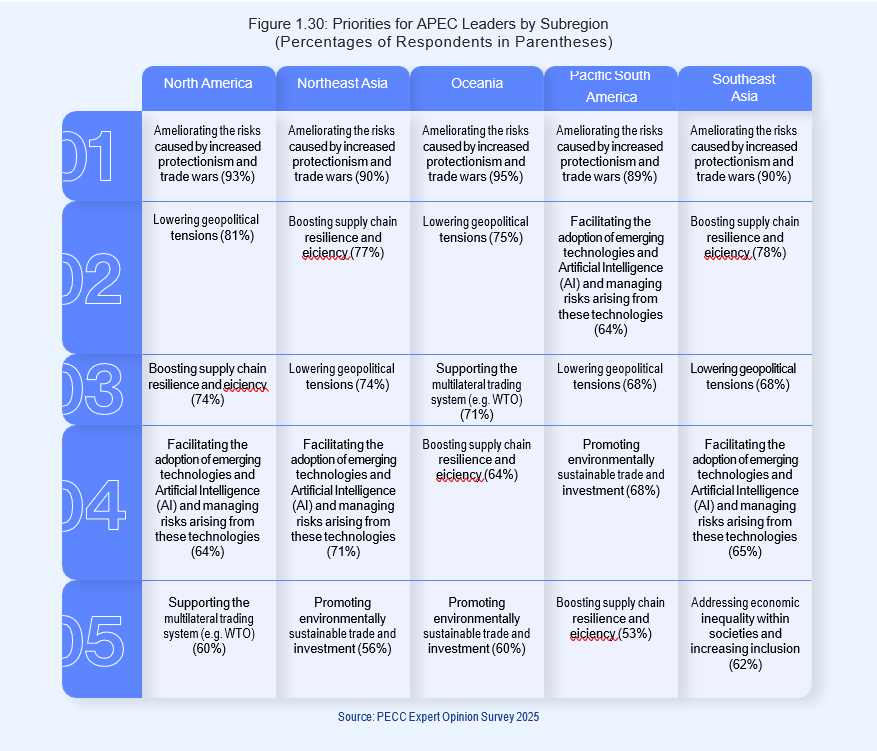

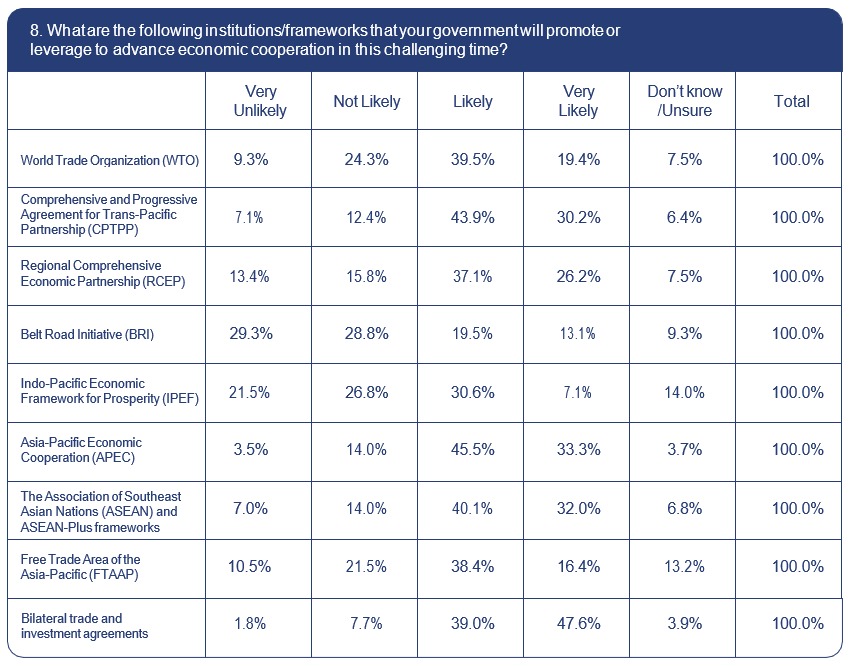

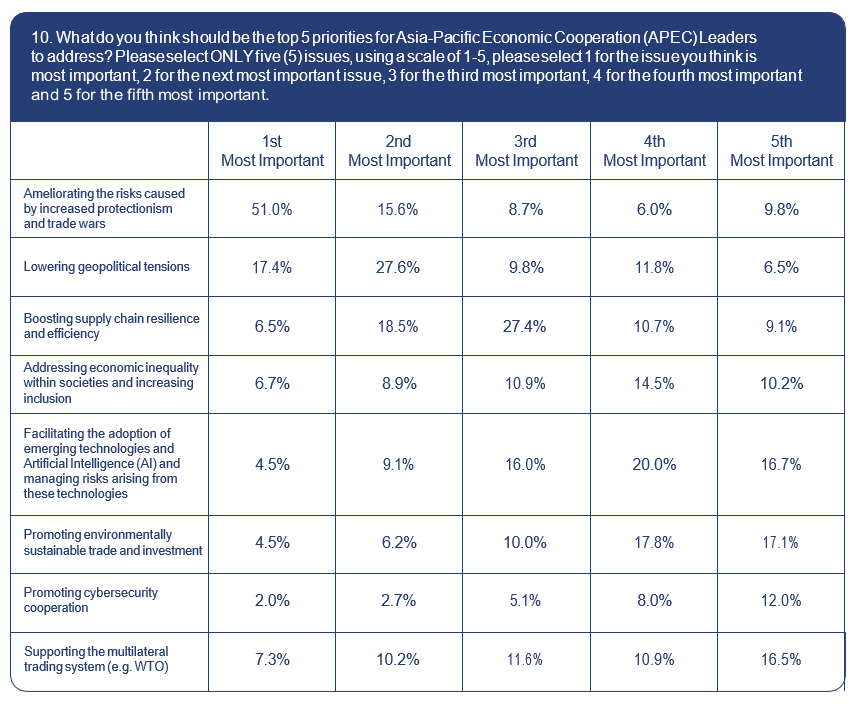

The top priorities for APEC leaders after managing the immediate protectionist risks, were identified as lowering geopolitical tensions, supporting the multilateral trading system, building supply chain resilience and addressing economic inequality (Figure 2.4). Managing the risks and capturing the benefits of new technologies, including artificial intelligence, and promoting environmentally sustainable trade and investment were also identified as priorities. The return of geopolitics, and the resultant securitization of economics, supply chain resilience, the dig- ital economy, including AI and cybersecurity, are discussed below. The return of elements of industrial policy, if not comprehensive industrial policies, in many economies to help deal with these challenges is also discussed.

New models for a future trading system are considered further below, recognizing the identi- fied priority as supporting an updated multilateral system from Figure 2.4.

The Return of Security in Economics

For decades, international economic risks were managed under the US-led, rules-based multilateral order established after World War II. The United States derived enormous benefits from this role, providing security, market stability, and safe assets in exchange for rule-setting privileges and dominant economic influence.6 Today, however, China’s rise as an economic power – and the U.S. response to it – has heightened concerns about fragmentation of the current economic order. A perception grew in the U.S. that while it abided by the rules, others did not. Unlike earlier economic competitors, who were largely security allies, China is far larger and viewed as a strategic rival, intensifying doubts about the durability of the system.

In this context, recent U.S. leadership has expressed deep skepticism about the fairness of the multilateral trading system. Bilateral trade imbalances are often cited as evidence of systemic bias. This perspective has justified a shift away from rules-based engagement and a turn toward more transactional, bilateral bargaining approaches aimed at correcting perceived inequalities and reshoring investment and economic activity to the U.S. While these strategies reflect longstanding domestic concerns about competitiveness and adjustment, they have also disrupted established multilateral practices. The frequent use of tariffs – sometimes adjusted mid-negotiation and at times deployed for non-economic purposes – has introduced greater uncertainty into the global trade environment. While the U.S. can exercise significant leverage in bilateral bargaining, most other economies continue to rely on the WTO as the primary framework governing their trade relations.

These U.S. shifts have coincided with wider global disruptions that were not primarily economic in origin but have had profound economic consequences. The COVID-19 pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, together with the resulting sanctions and countersanctions, have heightened uncertainty and underscored vulnerabilities in the multilateral trading system.

At the same time, the growing use of economic instruments – including sanctions, trade and financial restrictions, tariffs, and cyber-enabled measures – for strategic or political purposes has blurred the boundary between economic policy and national security and led many economies to view economic interdependence as a vulnerability instead of a source of prosperity and security.

6 Posen, Adam S. 2025. “The New Economic Geography.” Foreign Affairs, August 19. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/new-economic-geography-posen.

‘Economic security’, in broad terms, encompasses the protection of national economic interests, ensuring resilience to external shocks, and the maintenance of some level of strategic autonomy to react to circumstances as they evolve. At a fundamental level, national economic interests refers to living standards, income and necessities such as health, education and social protection.7 ‘Geoeconomics’ is often used to describe the intersection between economics and geopolitics, with the most widely used definition today as ‘the systematic use of economic instruments to accomplish geopolitical objectives’.8 In practice, the key concepts are the ability to withstand shocks and defend against coercion by other states.9

Today, national security concerns have become resurgent, entangled with other developments that include climate change, innovative environmental technologies, threats of new pandemics, domestic political instability and fractured social cohesion, as well as negative spillovers from great power rivalry. The responses to these concerns can be classified in two ways. Protectionism lowers economic efficiency to protect domestic interests, including that of national security considerations. Otherwise, pragmatic policies can disrupt the allocation of resources coming from an acknowledgement of new priorities, such as resilience or national security, that may have previously been unrecognized or unacknowledged. Governments need to adopt a nuanced approach that balances the opportunities and risks of international engagement. In contemporary policymaking, the security imperative is increasingly dominating the economic imperative. While there may sometimes be a trade–off between the two, and it may be important to maintain a strong national security stance, the assumptions and methodologies behind the decisions need to be clear. As much as possible, policy solutions should make economies both more prosperous and more secure.

Economic competition is often framed as a contest with multiple winners, or positive-sum, while security competition generally adopts a zero-sum framing.10 Economic competition occurs when an economy attempts to increase its productivity, for example by investing in education, supporting research and development, improving infrastructure, strengthening human capital, or removing trade barriers that hinder efficient resource use. Such measures enhance an economy’s performance while also generating positive spillovers for the rest of the world. By contrast, security competition emphasizes relative position: an economy seek advantage by constraining rivals, limiting their access to critical technologies, and pursuing strategies that prevent competitors from gaining ground. In this view, relative gains matter more than absolute gains, and economic interaction is treated as zero-sum.

7 Jacob S Hacker, ‘Economic security’ in Joseph E Stiglitz et al (eds), For Good Measure: Advancing Research on Well-being Metrics Beyond GDP (OECD Publishing, 2018) 203.

8 Robert D Blackwill and Jennifer M Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft (Harvard University Press, 2016) 1.

9 Miles Kahler, ‘Economic Security in an Era of Globalization: Definition and Provision’ (2004) 17(4) Pacific Review 485.

10 Ibid.

The strategic competition between the great powers, and weaponization of economic tools, is turning economics and security into substitutes where it increasingly seems that one has to be sacrificed to achieve the other, creating an unfortunate trade-off. Given that the risk of economic coercion from great powers will always exist, middle powers and smaller economies have an interest in building a system that constrains their baser instincts. There is no guarantee of security from retreating to closed markets, retaliating or seeking to make bilateral deals. The experience in the Asia Pacific has been that the best response to economic coercion is to ensure the existence of enforceable rules that disincentivise coercive measures and open contestable markets blunt their effectiveness.

What is the best strategy for the middle-sized and smaller economies in APEC? They should pursue policy agendas around the three goals: system preservation, system reform and collective action.11 The objective of system preservation rejects the false dichotomy of picking sides and reiterates a commitment to a multilateral system binding and benefiting all.

Many economies are perceiving that the United States and China are increasingly applying pressure to choose between them, imposing sticks such as sanctions and export restrictions and offering carrots such as preferred treatment for allies. It may seem economically and politically expedient for smaller economies to acquiesce to these terms, but that choice enables and validates the weakening of the existing international economic order. To avoid the binary of capitulating or retaliating, middle powers and smaller economies should adhere to the established rules in the WTO and other regional and bilateral agreements, regardless of what the great powers do – they may be blatantly disregarding the rules and norms of the established system, but they have not yet completely walked away from it. Economies need to also protect their core interest in the multilateral trading system that keeps markets open and ensures that engagement is based on rules. The international system has always had its flaws and is far from perfect, but for decades it has limited discrimination, promoted transparency, openness, fairness and predictability and constrained protectionism. Most of these principles have long been embedded in domestic practice in market economies and have been disseminated beyond through both the GATT/WTO as well as plurilateral and bilateral FTAs.

11 Ibid.

The clearest manifestation of a constructive effort to protect the system is in the dispute settlement body of the WTO. Following the U.S. veto of all nominations to the the Appellate Body, the WTO has been unable to meaningfully conclude trade disputes between its members. Since 2019, many disputes were effectively appealed ‘into the void’. But six months after the Appellate Body ceased to have the required number of judges to operate, the European Union and Canada led the creation of the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA), a plurilateral framework which duplicates the Appellate Body and enables willing parties to agree to resolve WTO disputes among themselves. Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and, importantly, China were among the original signatories.12 Japan joined in early 2023, with the grouping almost comprising a third of the WTO membership. Malaysia joined in 2025 during its ASEAN Chair year. The MPIA has worked to resolve trade disputes and is a clear expression of the interest in a rules-based system. Further expansion of MPIA membership will help insure against a complete collapse of dispute settlement as the WTO membership works to reform and restore the system.

In a world where great power competition makes cooperation difficult, the established-rule- based system needs to be protected and reformed around shared interests — as was done with MPIA and other plurilateral and regional arrangements. Efforts to reform and update rules are taking place incrementally through these plurilateral arrangements among like-minded economies and regional agreements shaped by shared interests and geographic proximity.

These are bottom-up processes that build on top of the existing system by developing new rules relevant for modern commerce. While they are often driven by both political and economic interests, they need not necessarily be inherently inconsistent with rulemaking that strengthens multilateralism.

Multilateralism is more likely to be sacrificed when security-based initiatives are deliberately designed to exclude certain economies. Proposals such as friendshoring or limiting trade to ‘trusted partners’ or like-minded economies risk shrinking the global economy and reinforcing a static view of the world built on permanent friends and permanent enemies. This dynamic is relevant amongst APEC economies, such as in East Asia, where diverse political systems coexist, but where most economies remain committed to international rules and open trade.

12 Shiro Armstrong, ‘Australia, Japan, and a Middle Power Approach to Securing Prosperity in Global Disorder’ (2025) 32(1) Asia-Pacific Review 80.

Arrangements that remain open to new members can contribute positively to expanding the multilateral system. Their long-term significance will depend on how their membership expands and whether they can be integrated into broader rulemaking efforts. Although many bilateral and regional economic agreements often contain preferential clauses that deviate from the principle of equal-treatment embodied in the MFN clause in the WTO, they are usually designed as WTO-plus agreements that complement, rather than substitute for, the multilateral trading body.

Arrangements like APEC provide a model of open regionalism, advancing economic cooperation and integration among members. APEC has also been a useful forum for modes of flexible cooperation that are palatable among a diverse membership unable to agree to legally binding commitments among themselves, such as the pathfinder approaches and concerted unilateralism. Arrangements that remain open to new members can contribute positively to expanding the multilateral system. For example, a CPTPP that does not engage China in possible membership negotiations for political reasons will not incentivise Chinese reforms or commitment to new rules and standards. Any such negotiations should not sacrifice core principles of the agreement in order to expand its membership.

The post-war economic order relied on the United States as both an architect and an enforcer, but collective action is much more difficult now in a multipolar world. Today, the US increasingly acts as a spoiler rather than a stabilizer. A Stackelberg leadership model, where a dominant actor moves first and others follow sequentially, is no longer feasible.13 The GATT, and later the WTO, helped avoid prisoner’s dilemma outcomes in trade while other global forums, such as the G20 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, created frameworks for cooperative macroeconomic policy. These equilibria no longer seem feasible and zero- sum outcomes now appear more likely. In this environment, developing repeat games, such as annual leaders’ meetings, defining punishment for deviating in the form of agreed-upon and enforceable rules, and creating the frameworks to incentivise collective action will be necessary.

13 Armstrong and Quah (n 10).

One possible option is plurilateralism or pathfinder multilateralism.14 A fractured global economy might rule out truly universal multilateral frameworks, but targeted arrangements can still preserve the ethos of collective problem-solving in targeted domains. These narrower initiatives, acting as pioneering models, can keep progress alive even when comprehensive multilateralism is out of reach. The MPIA is an illustrative example by allowing participating WTO members to resolve dispute among themselves, bypassing systemic gridlock while sustaining confidence in rules-based trade. By focusing on incremental, achievable collaboration among willing partners, such initiatives help preserve the spirit of multilateralism despite fragmentations.

Coordinating these types of plurilateral arrangements is not easy under a fragmented global system. The collective action problem, where individual interests diverge from group interests, risk paralysis. One possible solution to overcome this is through concerted unilateral action, where economies identify specific common objectives and take steps to pursue those goals unilaterally and voluntarily. This model was expounded in APEC through non- binding and voluntary cooperation which advanced trade and investment liberalization on the understanding that it was beneficial for individual economies and that the benefits would be increased as more economies adopted these policies - economies committed to a common cause and acted in their own-self-interests to the benefit of others.15 The ‘Bogor Goals’ agreed to at the APEC summit in 1994 – free and open trade and investment by 2010 for industrialised economies and by 2020 for developing economies – were not fully achieved, but they spurred unilateral liberalization in the Asia-Pacific and anchored a shared vision of openness that guided the region’s economic integration. Leadership was exercised collectively through the APEC process, distributing responsibility for progress across the membership. APEC economies coming to an agreement on a public good or common interest can help organize and motivate concerted unilateral action towards shared objectives. In the contemporary environment, the energy transition imperative and the public good of open markets could play a similar coordinating role.

14 Danny Quah, ‘Correlated Trade and Geopolitics Driving a Fractured World Order’ in Lili Yan Ing and Dani Rodrik (eds), The New Global Economic Order (Routledge, 2025) 54.

15 Hadi Soesastro, ‘Pacific Economic Cooperation: the History of an Idea’ in Ross Garnaut and Peter Drysdale (eds), Asia Pacific Regionalism: Readings in International Economic Relations (HarperEducational, 1994) 77.

The actions of the great powers in introducing subsidies, adopting security-justified protectionism, exercising economic coercion and ignoring the rules-based system and even their own past commitments, risk contagion and a race to the bottom that would fracture the multilateral system and threaten economic and political security. Acting collectively, small and middle-sized economies, perhaps working through pathfinder or plurilateral approaches in regional groupings such as APEC, can help preserve and strengthen the multilateral system, constraining the excesses of the great powers.

Supply Chain Resilience

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and other disruptions, some companies have shifted, with support or encouragement from governments, from hyper-efficient ‘just-in- time’ production networks towards ‘just-in-case’ strategies that prioritized reliability and risk reduction. This has meant larger inventories, more diversified supplier bases, and in some cases the relocation of production either at home or to politically friendly economies. The logic of supply chain resilience rests on two main ideas: that producing goods domestically secures supply, and that foreign suppliers might exploit market power for leverage.

The current adverse external circumstances gave rise to the notion that economies can and should seek security from the world.16 Confronted with great power competition, supply chain shocks, and fears of economic coercion, many economies turned inwards by adopting policies of self-reliance, protectionism and economic insulation. For some smaller economies, the assumption that reducing interdependence can protect against external risks is unrealistic because for them, isolation is not a viable strategy. Rather, a more effective means of achieving national security may be to establish a more cooperative external environment in which the need for such protection is diminished.

For example, for many economies the belief that domestic production can protect against trade extortion is a fallacy because local manufacturing often depends upon imported inputs. Building resilience through ‘just-in-case’ strategies is costly and defining what scenarios should be considered and what counts as ‘essential’ is inherently political and often arbitrary. Leaning towards self-reliance might seem to reduce vulnerability, but in practice, shifts in investment and production and can concentrate, rather than eliminates risk.

Greater international engagement can strengthen resilience in two ways. First, increasing the diversity of suppliers means that economies are less exposed to disruptions in any single economy including their own because adverse shocks in one region can be offset by substituting imports from elsewhere. In a free and open trading system, firms do not need to pre-empt where goods will come from and can source from whichever producer is most efficient and reliable at the time. Second, economic interactions between economies strengthen security by broadening the plurality of interests.

16 Armstrong, ‘Australia, Japan, and a Middle Power Approach to Securing Prosperity in Global Disorder’ (n 13

Foreign investment creates stakeholders with a vested interest in a partner’s prosperity. Russia’s strategic use of gas supplies as political leverage against Europe is sometimes cited as a counterpoint to the argument that interdependence promotes political security, but Russia was never deeply integrated into European supply chains. Europe’s energy dependence on Russia is qualitatively different from the complex webs of reciprocal economic interdependence in the European Union or East Asia, for example.17 In these regions, economic interdependence built on confidence in an open, rules-based multilateral system which has kept political rivalries and unresolved history in check.

17 Armstrong and Quah (n 10).

Today, economic interdependence is often seen as a security vulnerability. Instances of economic leverage being used as a tool of coercion have given rise to fears about trade dependencies. But the abuse of economic leverage for political purposes can only succeed when there is extreme market power. In all but a handful of products, restricting imports or imposing an export embargo has little to no effect in a competitive market as alternative buyers or suppliers can easily be found. And even when an economy attempts to use its economic leverage for geopolitical purposes in commodities where it has market power, the results do not always materialise as intended.

The multilateral trading system provides a buffer against the risk of coercion. Open markets and global trade rules raise the costs of coercion, dilute economic leverage, blunt the exercise of raw economic power and provide exit ramps. A free and open international trading system, underpinned by a multilateral rules-based order, is the best form of supply chain resilience.

The global economy is large and has many alternative buyers and suppliers, so long as markets remain open. Flexible markets allow firms to react and respond to shocks. Had markets been closed, with fewer alternative buyers and sellers, the economic damage would have been far more severe. This outcome was one of the key motivations for the development of the post-war economic order, with multilateral rules introduced to protect economies from the raw exercise of economic leverage.

If coercive leverage is exercised, affected economies can diversify their markets and seek substitutes, with some adjustment cost. Were it not for the confidence afforded by these multilateral rules, economies may retreat from specializing in their comparative advantage and purchasing from efficient producers through costly re-shoring and de-risking. High trade dependencies are now seen as a vulnerability to many governments because they have been weaponized by some governments. But without confidence in high trade shares and deep economic interdependence, specialization will not be realized consistent with comparative advantage, and efficiency and productivity will suffer.

The Digital Economy and Artificial Intelligence

A crucial aspect of modern commerce that lacks multilateral rules for the digital economy. That risks a fragmented digital economy system that can affect trade in goods and services, as well as investment while preventing productivity gains globally. Rules and norms for the digital economy and AI in regional and plurilateral arrangements will need to follow multilateral principles to avoid a fragmented system.

The digital economy has become a central driver of growth and productivity. Today, it accounts for more than 15 per cent of global GDP and has expanded at more than twice the pace of the broader global economy over the past decade.18 The S&P 500’s exposure to digital technology almost doubled from 23 per cent in 2010 to nearly 40 per cent in 2024,19 with the World Economic Forum estimating that 70 per cent of new value created over the coming decade will be driven by digitally-enabled platform business models.20

The digital economy has several unique features compared to traditional sectors. Information can be shared and transmitted across borders at virtually no cost and data is a non-rivalrous resource which can be used simultaneously by many actors, often with increasing returns.21 Data and software therefore carry features of ‘public’ goods, with their value multiplying through economies of scale and network effects. Digital platforms, such as search engines and messaging apps, are highly scalable and also derive value from the size of their networks. Because of these characteristics, restrictions on the flow of data, software and digital talent can significantly undermine productivity and innovation.

The rapid growth of the digital economy and frontier AI has exacerbated longstanding risks around privacy, cybersecurity, monopolies, and intellectual property, while also creating entirely new risks such as deepfakes, cybertheft, and misinformation. More systemic issues include vulnerabilities in computational infrastructure and the energy/environmental burdens of large-scale AI systems. Given the porous nature of digital borders and associated spillover effects, slowing the adoption of digital technologies in one jurisdiction cannot prevent risks arising elsewhere. This makes adopting a multilateral approach to digital governance essential for safety and productivity.

18 Zia Hayat, ‘Digital trust: How to unleash the trillion-dollar opportunity for our global economy’, World Economic Forum (online, 17 August 2022) <https://www.weforum. org/stories/2022/08/digital-trust-how-to-unleash-the-trillion-dollar-opportunity-for-our-global-economy/>.

19 Lewis Krauskopf, ‘The S&P 500’s wild ride to an all-time high’, Reuters (online, 20 January 2024) <https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/sp-500s-wild-ride-an-all- time-high-2024-01-19/>.

20 Hayat (n 23).

21 Shiro Armstrong and Jacob Taylor, ‘Multilateral Governance for the Digital Economy and Artificial Intelligence’ (Discussion Paper No 24-E-052, RIETI, April 2024).

But the digital economy is increasingly divided, and protectionism is on the rise. Governments are imposing restrictions on cross-border data flows, promoting national champions and mandating localization. In the absence of comprehensive multilateral rules, the governance of the digital economy remains highly fragmented through initiatives such as the WTO’s Joint Statement Initiative and the Japan-led Data Free Flow with Trust. The resulting ‘digital noodle bowl’ of bilateral and regional agreements risks fueling geopolitical rivalry and undermine economic dynamism and interdependence.

The economic costs of fragmentation are substantial. The sources of innovation and technological progress are increasingly diffuse: in 1960, the United States accounted for nearly 70 per cent of global R&D but by 2018 this had fallen to 28.8 per cent, with China accounting for 23.1 per cent, Japan in third place with 8.5 per cent and Germany in fourth with 7 per cent.22 China overtook the US in 2020 as the largest source of international patent applications, with Japan third and Asia accounting for 52.4 per cent.23 The WTO and OECD recently examined the economic impact and found that in a worst-case scenario of ‘full fragmentation’ where each economy shuts off data flows across borders, global GDP could be 4.5 per cent lower and global exports 8.5 per cent lower than if data flowed freely.24

Fragmentation is reinforced by three interrelated challenges: concentration, protection and exclusion. The concentration of digital power has left a small number of US and Chinese firms in control of the highest value inputs to digital systems, including data, software and talent.

For instance, in 2023, the ‘Magnificent Seven’ spent nearly twice as much on R&D as all US universities combined.25 Market power is particularly acute in the development of large-scale AI systems, which require resources that only a handful of firms can provide.

With the digital economy operating under a ‘winner takes all’ systems, governments are seeking to protect and localize their digital assets. The number of localization policies doubled worldwide between 2017 and 2021, raising costs for foreign firms and indirectly subsidising domestic players. Smaller economies risk exclusion from frontier innovation, forced instead into dependency on technology firms from major powers.

22 ‘Gross domestic spending on R&D’, OECD (Web Page, accessed 5 August 2025) <https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.html>.

23 Stephanie Nebehay, ‘In a first, China knocks U.S. from top spot in global patent race’, Reuters (online, 7 April 2020) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-pat-ents-idUSKBN21P1P9/>.

24 OECD and WTO, Economic Implications of Data Regulation: Balancing Openness and Trust (Report, 2025) 7.

25 Michael T Gibbons, ‘R&D Expenditures at U.S. Universities Increased by $8 Billion in FY 2022’, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (online, 30 November 2023) <https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf24307>.

Exclusion also persists across economies. Only 36 per cent of people in LDCs use the internet, compared to a global average of 66 per cent.26 Poor connectivity, high costs and low digital literacy keep billions outside the digital economy, worsening inequalities in education, employment, governance and health outcomes.

These challenges underline the need to develop a multilateral framework that more evenly distributes the benefits of digital and AI systems while collectively managing their risks.

Globally inclusive arrangements can align incentives, establish shared norms and constrain unilateral policies that fragment markets. Such a regime would recognize that there are differences between economies in the style of government, economic structure, digital maturity and attitudes to data privacy and trade and grant them sovereignty over domestic policies, but under an agreed set of rules that limit discrimination, promote transparency and predictability, and constrain protectionism.

Building this kind of framework requires cooperation across a wide spectrum of actors, from governments, technology firms, SMEs, investors, consumers and workers. Any regional initiatives in the Asia-Pacific should be founded on the principles of open regionalism and interoperability with global regimes. Existing plurilateral and regional agreements have sought to create rules and understandings between smaller groupings of economies. By their nature they are limited in membership and the coverage of issues, but they provide a foundation for future agreements in setting agreed standards and developing potential language for the regional and global architecture of digital agreements. An agenda built around technical cooperation, capacity building and experience sharing can help build confidence and trust, particularly through collaborative work in areas such as digital trade facilitation that offer real and demonstrable gains.

26 Robert Opp, ‘Committing to bridging the digital divide in least developed countries’, UNDP (online, 8 March 2023) <https://www.undp.org/blog/committing-bridg-ing-digital-divide-least-developed-countries>.

The New Industrial Policy

The world is witnessing a renaissance of industrial policy27, driven by a range of objectives such as geopolitical competition, perceived high value-added manufacturing sector employment, and the imperative to transition to a green economy. Large-scale subsidies for high-tech and green industries, once frowned upon under the Washington consensus where governments were expected to ‘get out of the way of markets’, are now back in fashion, posing new challenges for the trading system.

For example, the United States’ Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 committed roughly US$369 billion to clean energy, electric vehicles and related manufacturing.28 While its purported central aim was climate action, many provisions, such as tax credits for EVs using North American-assembled batteries, explicitly favour domestic or regional content.

Many of the provisions under the IRA have been rolled back by President Trump but his administration has certainly not eschewed the use of industrial policy, making big investments in critical technologies and artificial intelligence.29 The United States’ leadership in returning to industrial policy has prompted complaints from trade partners, as well as similar policies.

The European Union responded with its own Green Industrial Plan, relaxing state aid rules to channel funds into renewables, hydrogen and battery technologies. Former President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi also called for a European industrial plan to boost growth and competitiveness.30 In East Asia, Japan and South Korea have expanded support for semiconductors and batteries, partly in response to US and EU initiatives.

Proponents of this new wave of industrial policy argue that it is mission-oriented, targeting goals such as climate and the green transition, defensive in nature (for example, to respond to China’s industrial policy) and are therefore not explicitly protectionist in nature. But the line between mission-driven aims and protectionist outcomes are thin, especially where subsidies are tied to domestic content. Furthermore, outlining a new objective does not eliminate the well-understood risks of industrial policy in encouraging rent-seeking, the misallocation of resources and the likelihood of political capture.

27 Industrial policy refers to both generic industrial policy and climate-mitigation-driven industrial policy. Generic industrial policy can include domestic subsidies, import prohibitions, and tariffs, and is designed to support domestic industries and constituencies that the government believes are particularly important for economic growth or, simply, internal political advantage. Climate-mitigation-driven industrial policy is designed to support climate mitigation while at the same ensuring that certain domes- tic industries and constituencies benefit, where those benefits may (or may not) be needed to generate political support for the mitigation investments. While the goals of the two industrial policies may differ, they are both industrial policy.

28 ‘$369 billion in investment incentives to address energy security and climate change’, UN Trade and Development (Web Page, 16 August 2022) <https://investment-> policy.unctad.org/investment-policy-monitor/measures/4004/-369-billion-in-investment-incentives-to-address-energy-security-and-climate-change- >.

29 ‘ICYMI: President Trump Announces $92+ Billion in AI, Energy Powerhouse Investments’, White House (Web Page, 16 July 2025) <https://www.whitehouse.gov/ articles/2025/07/icymi-president-trump-announces-92-billion-in-ai-energy-powerhouse-investments/>.

30 ‘The future of European competitiveness: Report by Mario Draghi’, European Commission (Web Page, accessed 5 August 2025) <https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en>.

This surge of subsidies highlights a coordination problem. A global subsidy race risks distorting competition, penalising smaller economies and eroding the level playing field. WTO rules on subsidies were not designed for a scenario in which major economies simultaneously subsidise strategic sectors. If every economy attempts to out-subsidise the others, the result will be spiralling distortions and inefficiencies. Some frictions are already evident, with European officials fretting that the US IRA would lure green-tech investments away from Europe while developing economies worry that they cannot compete with the scale of rich- economy subsidies.

This dynamic underscores the need for new or updated international rules, such as a framework for green subsidies that balances climate imperatives with fair competition, or greater transparency and agreed limits on technology subsidies. IMF First Deputy Managing Director Gita Gopinath has called for international norms on industrial policies, warning that without discipline they risk escalating retaliation and fragmentation.31 If it is properly coordinated, industrial policy could be harnessed in a cooperative way where economies pool resources to scale up clean technologies while sharing the gains more broadly.

For economies in the Asia-Pacific, the lesson is to not copy wholesale the policies of larger economies without considering their own interests. For example, Australia has a distinct policy challenge. Unlike the United States or the European Union, it does not compete directly with China in the manufacturing sector. The United States and Europe may view China’s technological ascent as a threat, but for Australia the benefits lie in access to cheaper, higher- quality goods — while tariffs on cars are a central issue for the EU and US, Australia, which

no longer has a car manufacturing industry, benefits more from consumption than protection. Instead, Australia’s prosperity depends on its resource exports, particularly iron ore, which underpins China’s industrial capacity and Australia’s fiscal base. Australia is indispensable to China’s economic security because its iron ore has no substitute in quality or quantity and will continue to more than half of China’s steel industry for the next decade. In turn, Australia is heavily reliant on resource trade with China which was worth A$317 billion in 2021 – 30 per cent of two-way trade while all G7 industrial economies combined account for 26 per cent.32

32 Shiro Armstrong et al, Economic Tools for Statecraft and National Security (Report, 2022).

Australia’s interests lie in managing interdependence strategically. Given that Australia provides crucial inputs for Chinese industrial production, rather than competing directly with its outputs, distancing itself from China would be economically counterproductive especially as China is likely to be a leader across many future technologies, including those that help with the green transition. Instead, building interdependence with China in critical minerals and in the transformation that will need to happen in steelmaking to achieve decarbonization goals will contribute to Australia’s prosperity and security. History shows that denying rising powers access to resources can fuel insecurity and conflict, as it did for Japan in the lead up to World War II.

This has implications for Australia’s industrial strategy, which is manifest under the Future Made in Australia (FMIA) agenda. FMIA is reflective of the global turn towards industrial policy, committing public resources to secure investment in critical minerals, renewable energy, green hydrogen, low-carbon steel and advanced manufacturing. But for a medium-sized open economy like Australia, the greatest benefits will come from positioning its industrial policy so that it complements rather than substitutes for openness, leveraging its comparative advantage in resources and clean energy to further deepen its integration in global value chains.

Models for a Future Trading System

Given the turbulent state of global trade, it is useful to envision possible models for the future trading system. Broadly, we can imagine three archetypes: a return to rules-based multilateralism, a relapse into a fragmented ‘might is right’ regime of mainly bilateral power- based deals, or a hybrid disorder that mixes elements of both. Each has very different implications for economic outcomes and global stability.

How the new issues in global trade of security in economics, supply chain resilience, the digital economy and AI, and the return of industrial policy are managed and navigated globally will be important to determining the characteristics and nature of the future trading system.

A revitalized rules-based multilateral system, preserving the core principles of non- discrimination, transparent and neutral but less bureaucratic dispute settlement is the most desirable model. Historically, the multilateral system has underpinned stable growth by internalizing political and security risks. The rules-based order, developed from the Bretton Woods institutions, helped to curtail protectionism and separated trade policy considerations from national security and geopolitics.33 Over the next eight decades, the multilateral trading system — built on the principle of equal treatment and a level playing field— progressively help make the global economy more open and insured against economic shocks and aggression.

The large global economy, with its alternative buyers and suppliers, protects economies against trade stoppages, whether politically motivated or from other shocks. The rule of law in the international economic system, as opposed to the rule by power, is the fundamental principle guiding international cooperation, requiring a WTO-centred system where disputes are adjudicated and externalities are managed collectively. To effectuate this vision, the WTO must be able to update its rules and finalize new agreements on digital trade, services, investment facilitation and environmental goods so that economies operate under a common set of modern rules. What is necessary to build is confidence in the system and that requires participants to act within the rules and norms of that system.

The second model is a relapse into ‘might is right’ transactionalism, where power politics dominates trade. In this scenario, large economies or blocs set the terms of trade deals to favour themselves, and smaller economies have little recourse but to acquiesce or form their own spheres. This model is reminiscent of trade in the Cold War, where there was little trade between the Western and Soviet bloc.34 Even within the USSR-dominated bloc, trade was limited and conducted through politically managed arrangements – often resembling barter or clearing mechanisms – rather than through transparent, rules-based systems reflecting market forces. The economic risks of such a world are enormous — production would be diverted from the most efficient locations to merely the politically ‘safe’ locations, raising costs and reducing innovation. IMF research has compared current fragmentation trends to Cold War patterns, finding that while fragmentation so far is modest relative to the Cold War, if it escalated it could impose huge costs because today’s global economy is far more interdependent than it was in 1950. Trade now accounts for 45 per cent of GDP, compared to 16 per cent at the start of the Cold War.35 If conditions deteriorate to extreme levels, it could lead to elements of the 1930s when nations erected high tariffs and discriminatory trade blocs fuelled economic rivalry and mistrust. In that decade, zero-sum economic competition exacerbated nationalism on the road to World War II. Indeed, it was the lessons from that experience that led to the creation of the GATT, which separated trade and international economic policies from the ‘high politics’ or ‘high foreign policy’ matters of national security and survival.36 Today, these hard-won gains should not be taken for granted. Proposals to replace open trade with preferential and discriminatory trade and investment policies for allies, democracies, or trusted partners will reduce economic options and concentrate markets, ultimately making economies more vulnerable to the very risks they seek to avoid.

34 Gita Gopianth et al, ‘Changing global linkages: A new Cold War?’ [2025] (153) Journal of International Economics 104042.

35 Gopinath (n 4).

36 Cooper, ‘Trade Policy is Foreign Is Foreign Policy’ (n 5).

Between these two poles is a hybrid disorder, characterised by zero-sum politics and unmanaged risks but without a full bifurcation into closed blocs either, which is not far from where we seem to be heading today. Trade based largely on market forces might continue globally in non-sensitive sectors such as consumer goods and commodities but tend to become more restricted in strategic sectors such as technology and defence-related goods or sectors with domestic political clout dominated by perceived “national champions.” Maintaining small yards and high fences around those sectors is not easy as mission creep has already occurred in many economies with the yards growing. The result is a kind of unstable equilibrium which avoids an outright comprehensive economic war but is not a reliable rules-governed system either since sectoral disputes will continue to expand. In such an environment, the political rhetoric will be characterized by zero-sum thinking as leaders will perceive economic gains for rivals as a loss for themselves. The defining feature of zero- sum thinking is that one side wins only when the other loses. This zero-sum perspective can be seen in the contemporary US-China rivalry over technological primacy in the 21st century. Unless this narrative can be flipped, it will progressively edge out possible areas for compromise that could lead to a healthier and more stable global economy for all. But that engagement seems to have moved to something even worse than zero-sum. From the perspective of the global economy, at least in zero-sum competition whatever one side loses, someone else gains. The tragedy is when economies undertake actions that produce losses for everyone — an epic-fail situation, where everyone can in principle be made better off but each economy seeking to advance their self-interest leads to an equilibrium where everyone is worse off. It is for this reason that this ‘in-between’ outcome is also a bad equilibrium.37 In this environment, zero-sum games lead to negative sum outcomes, and the lack of rules mean that security and political interests overwhelm economic imperatives.

37 Armstrong and Quah (n 10).

In a time of uncertainty, governments and firms tend to self-insure against risk with costly measures like hedging, diversification, stockpiling and other restrictions. But in the past, it was the rules-based system which managed these risks. Fortifying the economy against shocks in the name of economic security and resilience through subsidies and stockpiling comes at a significant cost to the government budget and is paid for by the taxpayer. The key question is whether pursuing insurance measures is a better approach than working to protect and reinforce the existing, cost-minimizing system. Instead of each economy expending resources on trade wars or resilience or industrial policy or duplicative systems, all economies can benefit from the efficiencies of a single integrated global market where risks are managed through the multilateral rules-based system.

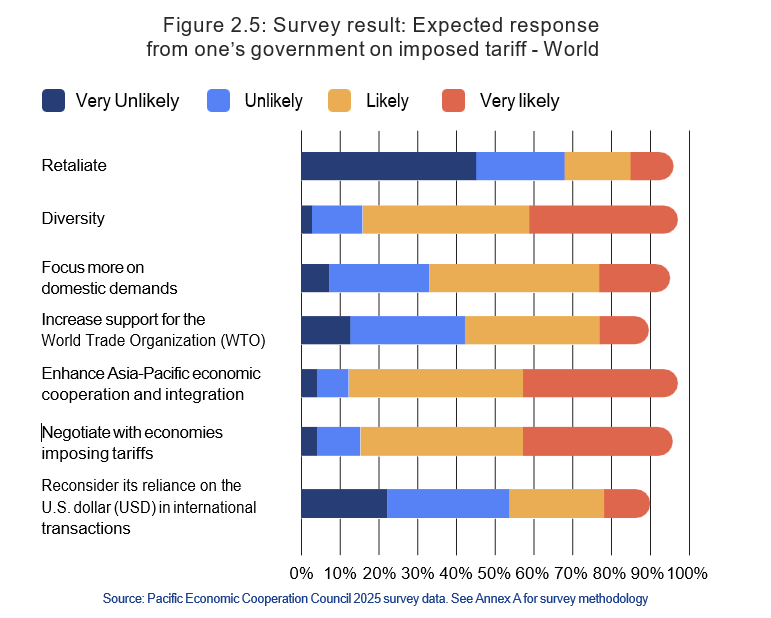

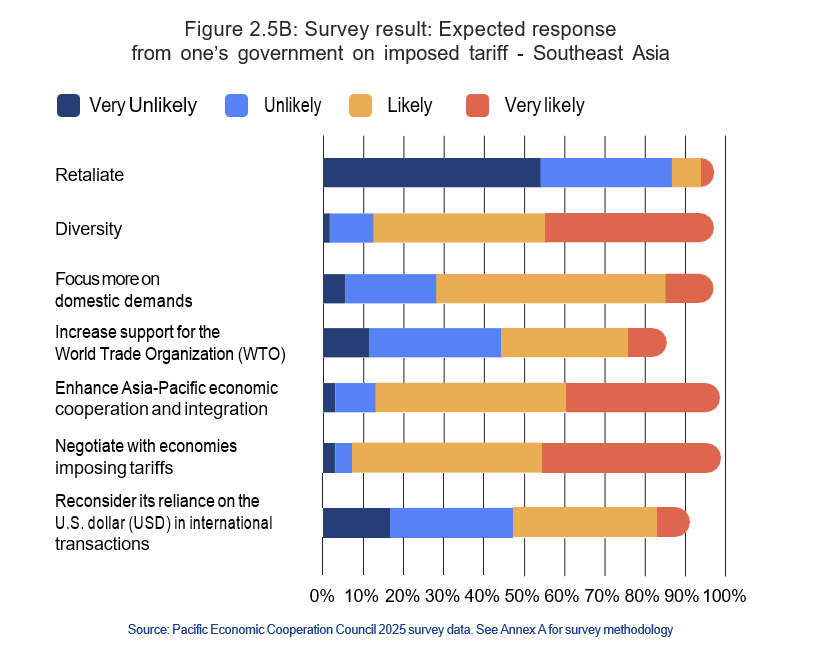

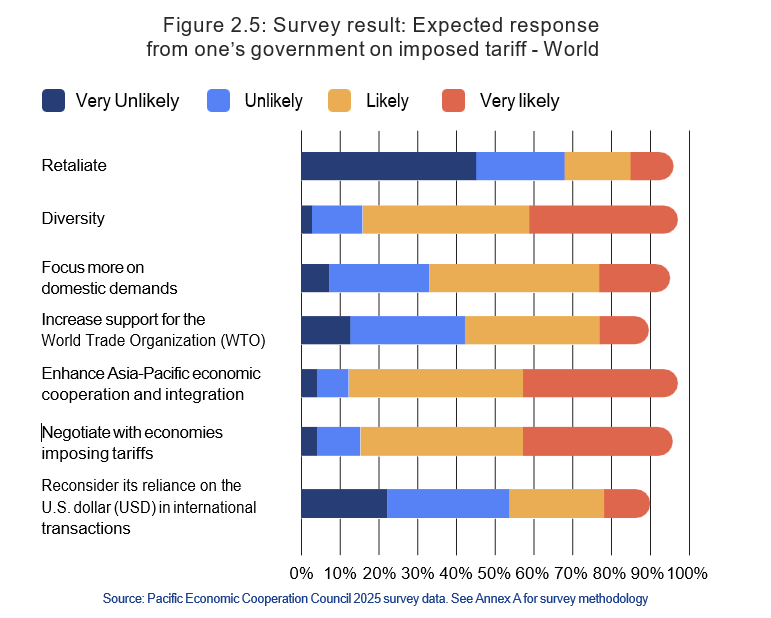

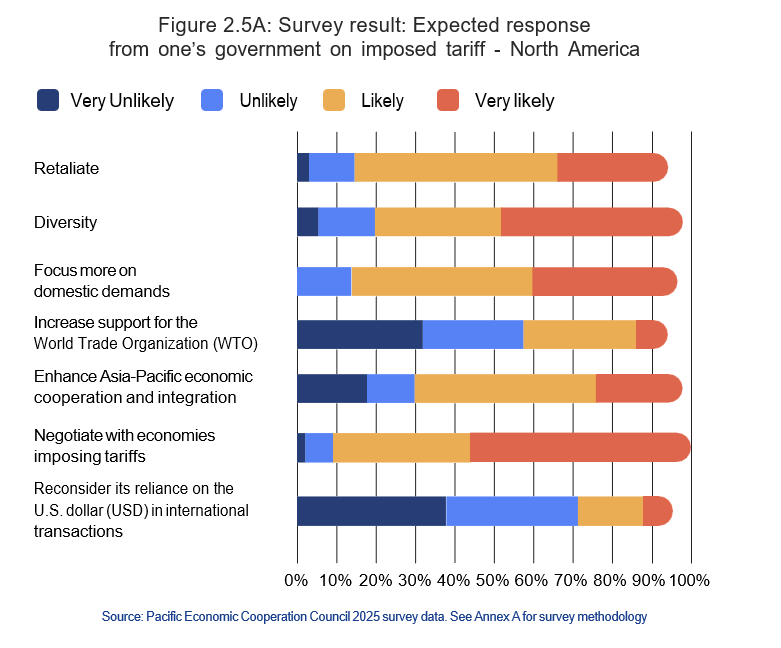

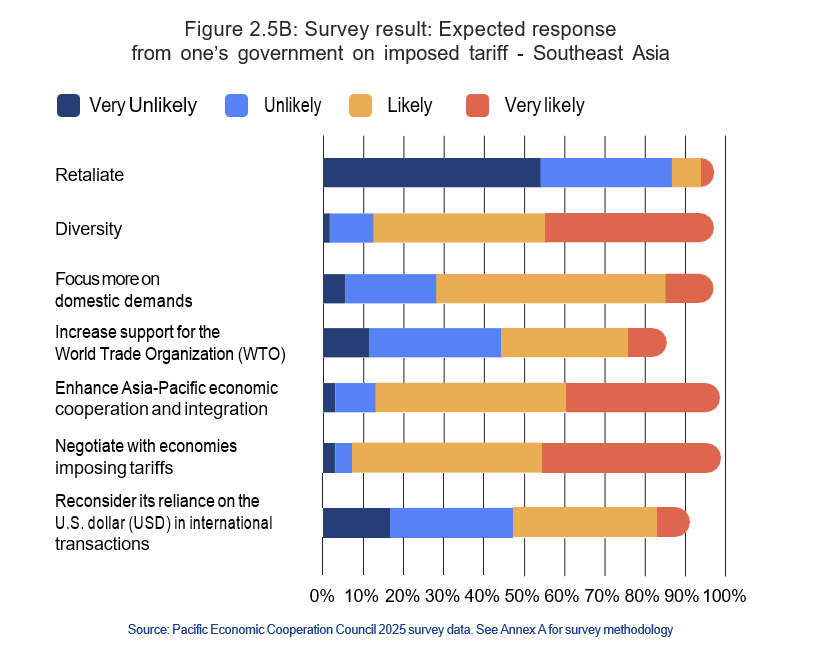

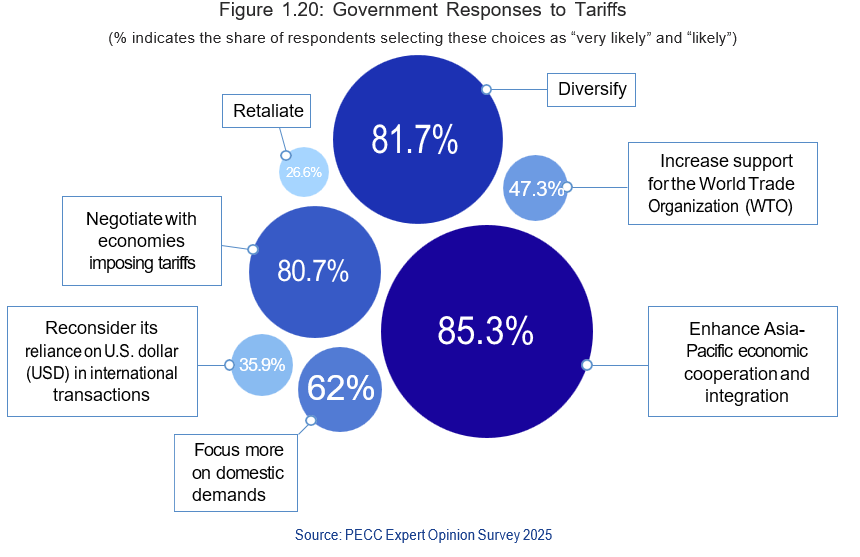

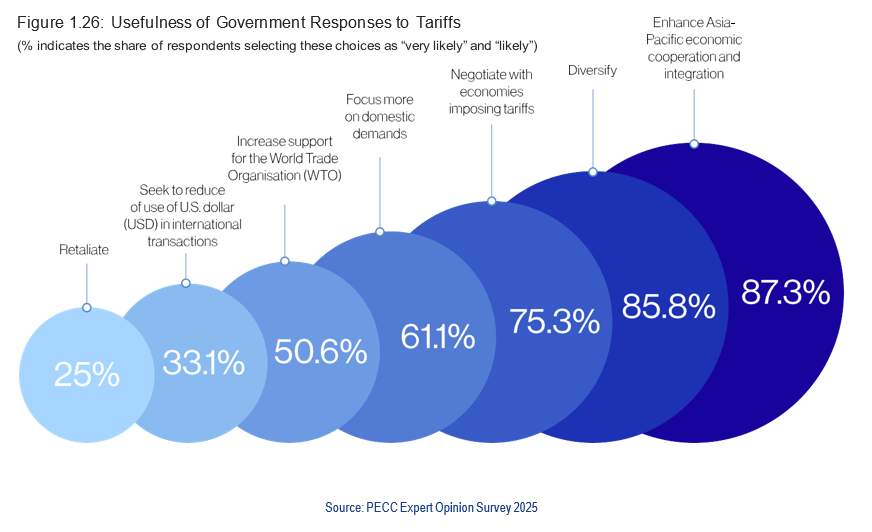

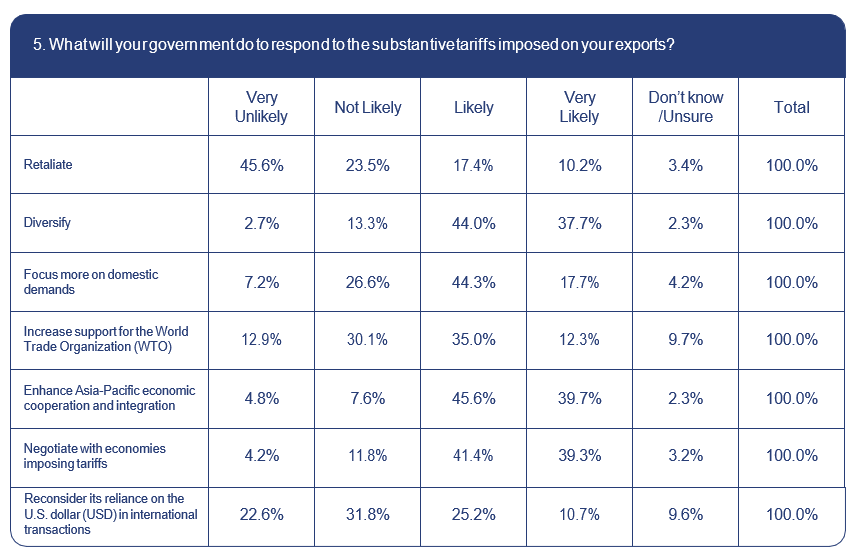

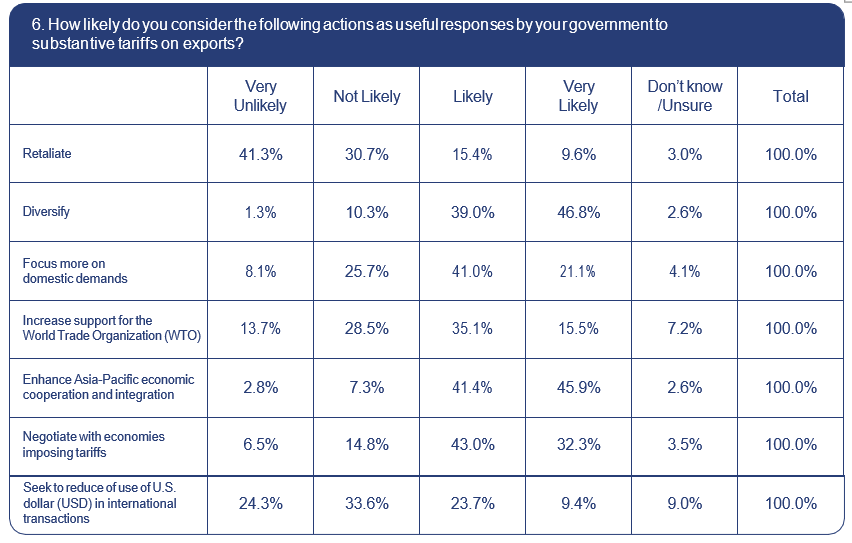

Figure 2.5 shows the expected response of governments on tariffs and other protectionist measures that hinders one’s trade. Many governments — such as Southeast Asian economies (Figure 2.5B) lean towards diversification, increase domestic demand and consumption (self- sufficiency), enhance APEC cooperation and integration as well as the need for continuous engagement and negotiation with economies imposing tariffs and protectionist measures.

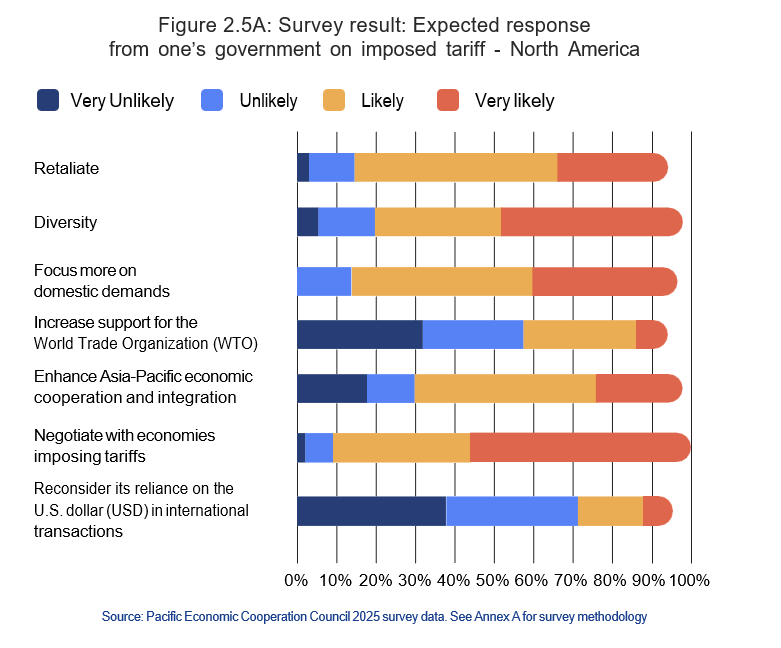

Breaking the results down further to show regional examples, North American economies are the only economies that expect their governments to retaliate (Figure 2.5A).

As Figure 2.5 shows the results on the expectation for governments to “increase support for the World Trade organization (WTO)”, the value, relevance, and importance of the rules- based multilateral trading system to the global community have not changed. It continues to be a counterweight to protectionism, while an open trading system, with substitute markets and alternative suppliers, remains a critical buffer against economic shocks. It is the loss of confidence in the system — not any flaw in the system itself — that is driving economies and companies to self-insure through diversification, stockpiling, friendshoring, and other policy measures in the name of economic security. This is not a safer or more desirable world: it is a set of third-best policy responses in a second-best world that reduces our chances of reaching a first-best solution. Working to restore and defend the system is a better, cheaper and more reliable way to manage risks. The rules-based system, for all its current troubles, remains the proven architecture that can manage interdependence with minimal friction.

Conclusion

In this era of disruption and disorder, the rules-based international economic order is at risk of devolving into a bilateral ‘might-is-right’ world that leaves economies constantly appeasing the latest developments and the whims of the great powers. To avoid that trajectory, economies must clearly define the interests they will defend and adopt strategies that safeguard national priorities while keeping international policy choices open in an increasingly power-driven world.

If great powers practice coercion, smaller economies and even middle powers must decide whether to look for bilateral deals, hit back with counter-tariffs, or stay the course. US tariffs and trade restrictions have seen economies seek out bilateral deals. The great temptation will be to negotiate managed trade deals, voluntary export restraints, or some form of exemptions. But while such outcomes may seem the least bad option from a business perspective, they erode systemic multilateral trade rules. If this becomes normalized as an accepted precedent, the choices that the great powers may force on other economies will only get sharper, further accelerating the breakdown of the global economic order. A coordinated multilateral approach, including concessions where necessary, can reduce the risk of trade diversion, while institutions such as APEC offer platforms to manage and coordinate both positive and negative spillovers.

The Asia-Pacific, with high trade to GDP ratios, has benefitted more than any other region from the open trading system and is especially vulnerable to disruptions. But it also has the institutional innovations (CPTPP, RCEP, APEC) necessary to lead a proactive regional strategy in response to the new global economic landscape. CPTPP brings together economies across Asia and the Americas in a high-standard agreement that covers issues from intellectual property to digital trade and is open to new members, exemplifying open regionalism in practice. RCEP, led by ASEAN and including large regional economies like China and Japan,

is the world’s largest regional trade agreement, includes an in-built agenda for economic cooperation and was concluded during a period of rising protectionism, demonstrating a commitment in Asia to keep markets open. APEC also continues to be valuable as a non- binding forum where major economies of the Pacific Rim, including the US and China discuss trade and economic issues on equal footing. It has a consensus-based approach and important initiatives, such as mutual recognition arrangements, which build practical cooperation and trust and incubate ideas.

By strengthening regional partnerships with economies that face similar challenges, clearly articulating their economic security interests and engaging in sustained diplomacy, the Asia- Pacific can foster a collective response to economic uncertainty. The region should pursue three big priorities.

PRIORITY ONE

First, the region needs to provide leadership to preserve and reform the international rules- based system. The WTO remains the lynchpin of a rules-based trading system and expanding MPIA, which includes China and other major Asian economies, will bring more members under a system of enforceable rules and increase certainty in trade. There is also an urgent need to update the WTO rulebook to address areas currently at the root of trade frictions, crafting disciplines or transparency agreements on industrial subsidies, clarifying the scope of national security exceptions, and making progress on digital trade rules. Article XXI of the GATT permitted nations to enforce limiting measures for legitimate national security interests, but the allowance was never meant to be universal and there existed a norm to avoid undermining of GATT’s rules through excessive use under the guise of national security. The rules-based trading system is at risk if WTO members can deploy discriminatory tariffs, quotas or other trade restrictions with their own interpretation of national security without a functioning dispute settlement system, and there is a need for groups of economies to codify what legitimate national security interests are and under what conditions Article XXI in the GATT can be invoked. Restoring norms around the Article’s use and credibly committing to those bounds through agreements can help preserve the rules-based trading system. WTO reform should also improve regular functions such as the monitoring of trade policies and strengthening technical assistance for developing members. The key aim of preserving the WTO is in preserving good habits — the inclination towards cooperation and the expectation of reciprocity — which leads even large economies to find themselves constrained by multilateral rules.

PRIORITY TWO

Second, economies in the Asia-Pacific need to ensure that regional and plurilateral agreements are integrated into the global system. As regional trade agreements and plurilateral initiatives proliferate, they must align with multilateral principles with a view to ultimately spread their gains. RTAs should be designed in a way such that they complement multilateral institutions, rather than substitute for them. Major agreements such as RCEP and CPTPP should be open platforms, encouraging accession by any economies that are willing to meet the rules of the agreement, and plurilateral deals should ideally be designed in a way that they can be brought into the WTO framework when ready. This applies to the development of rules and norms for the digital economy and AI.

PRIORITY THREE

Third, the green transition should be pushed as a unifying goal for concerted unilateral action. In the absence of formal multilateral agreements, economies need to be encouraged to undertake domestic reforms voluntarily. The concerted unilateralism approach sees economies converge towards a common goal according to their domestic circumstances. But it needs an organizing goal and climate change — an existential challenge that necessitates cooperation, open trade and investment in green goods and services, harmonized regulations and the cooperative management of spillovers — can be that mission. Trade is a necessary part of the green transition and climate agenda, allowing the diffusion of green innovation and creating new markets and jobs. Trade policies should be part of the solution, not the problem, and agreements should be pursued to liberalize environmental goods and services, coordinate on climate-related trade policies such as CBAM to prevent fragmentation and constrain economies from introducing green policies that restrict investment or foreign content.

The rules-based multilateral trading system is under threat. The future of the global economic order is not predetermined but shaped by choices and it is not exogenous to policy influence. The current trajectory on which we find ourselves is a result of deliberate decisions, and purposeful actors can influence this trajectory through proactive and coordinated policy efforts. For economies in the Asia-Pacific, copying the policies of great powers — who have much greater resources, geopolitical leverage, and ability to absorb economic costs — without careful consideration of their implications risks leading the world toward an outcome in which all are worse off due to narrowly self-interested national choices, despite the potential for better outcomes through international cooperation. In a disrupted world, the best trade policy is to defend and strengthen the institutions that had provided prosperity, certainty and stability for so many decades.

References

- ‘$369 billion in investment incentives to address energy security and climate change’, UN Trade and Development (Web Page, 16 August 2022) <https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-policy-monitor/measures/4004/-369-billion-in-investment-incentives-to-address-energy-security-and-climate-change->.

- Armstrong, Shiro, ‘Restoring the Global Trading System with Collective Action’, RIETI (online, 20 December 2023) <https://rieti.go.jp/users/shiro-armstrong/serial/008.html>.

- Armstrong, Shiro, ‘Australia, Japan, and a Middle Power Approach to Securing Prosperity in Global Disorder’ (2025) 32(1) Asia-Pacific Review 80.

- Armstrong, Shiro and Jacob Taylor, ‘Multilateral Governance for the Digital Economy and Artificial Intelligence’ (Discussion Paper No 24-E-052, RIETI, April 2024).

- Armstrong, Shiro et al, Economic Tools for Statecraft and National Security (Report, 2022).

- Blackwill, Robert D and Jennifer M Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft (Harvard University Press, 2016).

- Cooper, Richard N, ‘Economic Interdependence and Foreign Policy in the Seventies’ (1972) 24(2) World Politics 159.

- Cooper, Richard N, ‘Trade Policy is Foreign Is Foreign Policy’ [1972–73] (9) Foreign Policy

- George, Libby, ‘$400 billion debt burden: Emerging economies face climate action crisis’, World Economic Forum (online, 19 April 2024) <https://weforum.org/stories/2024/04/debt-burden-emerging-economies-face-climate-action-crisis/>.

- Gibbons, Michael T , ‘R&D Expenditures at S. Universities Increased by $8 Billion in FY 2022’, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (online, 30 November 2023) <https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf24307>.

- Gopinath, Gita, ‘Geopolitics and its Impact on Global Trade and the Dollar’ (Speech, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, 7 May 2024).

- Gopianth, Gita et al, ‘Changing global linkages: A new Cold War?’ [2025] (153) Journal of International Economics 104042.

- ‘Gross domestic spending on R&D’, OECD (Web Page, accessed 5 August 2025) <https://oecd.org/en/data/indicators/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.html>.

- Hacker, Jacob S, ‘Economic security’ in Joseph E Stiglitz et al (eds), For Good Measure: Advancing Research on Well-being Metrics Beyond GDP (OECD Publishing, 2018) 203.

- Hayat, Zia, ‘Digital trust: How to unleash the trillion-dollar opportunity for our global economy’, World Economic Forum (online, 17 August 2022) <https://weforum.org/stories/2022/08/digital-trust-how-to-unleash-the-trillion-dollar-opportunity-for-our-global-economy/>.

References

- Hirschman, Albert O, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (University of California Press, 1945).

- ‘ICYMI: President Trump Announces $92+ Billion in AI, Energy Powerhouse Investments’, White House (Web Page, 16 July 2025) <https://whitehouse.gov/articles/2025/07/icymi-president-trump-announces-92-billion-in-ai-energy-powerhouse-investments/>.

- Kahler, Miles, ‘Economic Security in an Era of Globalization: Definition and Provision’ (2004) 17(4) Pacific Review 485.

- Krauskopf, Lewis, ‘The S&P 500’s wild ride to an all-time high’, Reuters (online, 20 January 2024) <https://reuters.com/markets/us/sp-500s-wild-ride-an-all-time-high-2024-01-19/>.

- Montesquieu, Charles de, The Spirit of the Laws, ed Anne M Cohler, Basia Carolyn Miller and Harold Samuel Stone (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

- Nebehay, Stephanie, ‘In a first, China knocks S. from top spot in global patent race’, Reuters (online, 7 April 2020) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-patents-idUSKBN21P1P9/>.

- OECD and WTO, Economic Implications of Data Regulation: Balancing Openness and Trust (Report, 2025)

- Okuda, Tatsushi and Tomohiro Tsuruga, ‘Geoeconomic Fragmentation and International Diversification Benefits’ (Working Paper No 24/48, International Monetary Fund, March 2024).

- Opp, Robert, ‘Committing to bridging the digital divide in least developed countries’, UNDP (online, 8 March 2023) <https://undp.org/blog/committing-bridging-digital-divide-least-developed-countries>.

- Polanyi, Karl, The Great Transformation (Beacon Press, 1957).

- ‘Trade tensions and rising uncertainty drag global economy towards recession’, UN Trade and Development (Web Page, 25 April 2025) <https://unctad.org/news/trade-tensions-and-rising-uncertainty-drag-global-economy-towards-recession>.

- Quah, Danny, ‘Correlated Trade and Geopolitics Driving a Fractured World Order’ in Lili Yan Ing and Dani Rodrik (eds), The New Global Economic Order (Routledge, 2025) 54.

- Soesastro, Hadi, ‘Pacific Economic Cooperation: the History of an Idea’ in Ross Garnaut and Peter Drysdale (eds), Asia Pacific Regionalism: Readings in International Economic Relations (HarperEducational, 1994)

- Smith, Adam, The Wealth of Nations (W Strahan and T Cadell, 1776).

- ‘The future of European competitiveness: Report by Mario Draghi’, European Commission (Web Page, accessed 5 August 2025) <https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en>.

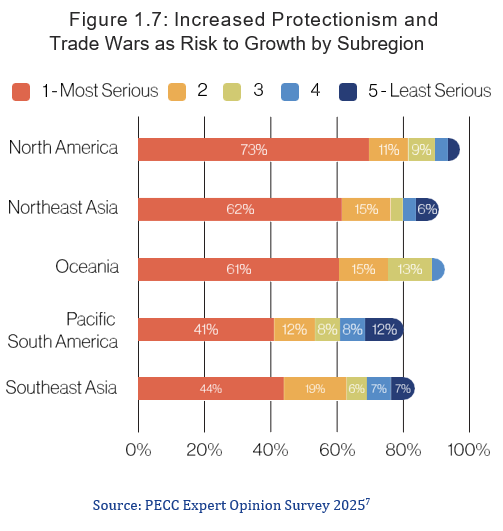

Different subregions possess divergent perspectives (Figure 1.7). For instance, 73% of respondents from North America choose “increased protectionism and trade wars” as their “most serious risk”. This may be because this subregion houses the economies most exposed to the US market. For example, Mexico’s and Canada’s goods exports to the US account for 28% and 19% of their GDP respectively. Also, 62% of survey subjects from Northeast Asia and 61% from Oceania consider the issue as their “most serious risk”, indicating serious concerns. This may be because the US remains one of their major trading partners.

Different subregions possess divergent perspectives (Figure 1.7). For instance, 73% of respondents from North America choose “increased protectionism and trade wars” as their “most serious risk”. This may be because this subregion houses the economies most exposed to the US market. For example, Mexico’s and Canada’s goods exports to the US account for 28% and 19% of their GDP respectively. Also, 62% of survey subjects from Northeast Asia and 61% from Oceania consider the issue as their “most serious risk”, indicating serious concerns. This may be because the US remains one of their major trading partners.

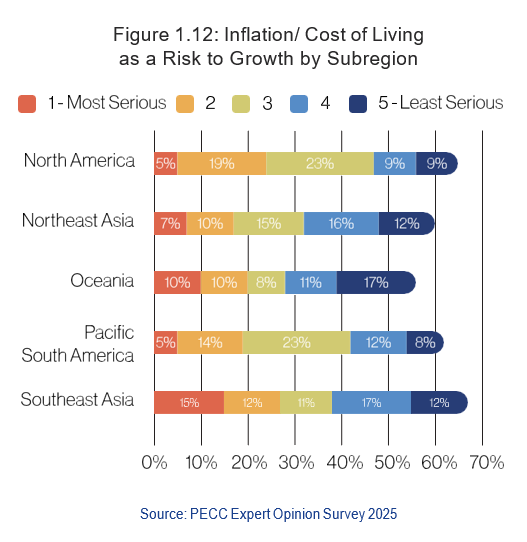

A close look at the PECC survey reveals that perspectives on inflation differ across subregions (Figure 1.12). Southeast Asian and North American individuals are most concerned, with 67% of the former and 65% of the latter pick it as their risk to growth.

A close look at the PECC survey reveals that perspectives on inflation differ across subregions (Figure 1.12). Southeast Asian and North American individuals are most concerned, with 67% of the former and 65% of the latter pick it as their risk to growth.

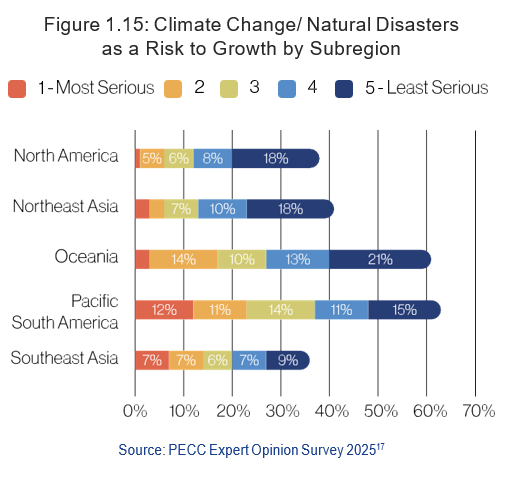

The PECC survey uncovers cross-subregional variations (Figure 1.15). Respondents living in Pacific South America and Oceania are the most worried. About 60% of these individuals cite the issue as their risk to growth, as compared to about 36-42% of their counterparts elsewhere. This result may be attributed to the two subregions’ unique geographical vulnerabilities. Illustratively, Oceania has several low-lying islands or communities. Rising sea levels cause coastal erosion and freshwater contamination, threatening their livelihood and existence.

The PECC survey uncovers cross-subregional variations (Figure 1.15). Respondents living in Pacific South America and Oceania are the most worried. About 60% of these individuals cite the issue as their risk to growth, as compared to about 36-42% of their counterparts elsewhere. This result may be attributed to the two subregions’ unique geographical vulnerabilities. Illustratively, Oceania has several low-lying islands or communities. Rising sea levels cause coastal erosion and freshwater contamination, threatening their livelihood and existence.

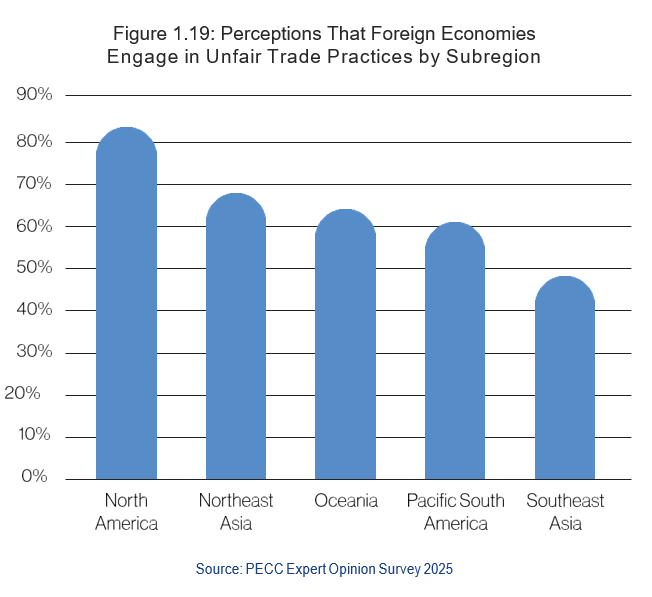

“Rising economic inequality within societies” emerges as the third most important concern about trade and globalization, with 68% of survey subjects choosing it (Figure 1.18). The issue has worsened in the past three decades. During this period, income inequalities in more than half of all economies and close to 90% of advanced ones were widened.23 This phenomenon may be explained by various elements ranging from new technological innovations, unequal access to finance, to stringent labor markets.

“Rising economic inequality within societies” emerges as the third most important concern about trade and globalization, with 68% of survey subjects choosing it (Figure 1.18). The issue has worsened in the past three decades. During this period, income inequalities in more than half of all economies and close to 90% of advanced ones were widened.23 This phenomenon may be explained by various elements ranging from new technological innovations, unequal access to finance, to stringent labor markets.