Pacific Currents

The Linkage between Services and Manufacturing in the US economy

Sherry M. Stephenson

Senior Fellow

International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development

Services have enabled manufacturing in the U.S. to become more efficient and competitive

Services have enabled manufacturers to take advantage of cutting edge technologies and become more productive. Services have also enabled manufacturers to grow the value of their operations from the initial stage of designing their products to the final stage of getting their products to their customers. Manufacturing has become a complex mix of many types of services, automation, and computer-driven production, with a large and growing share of value derived from the services components.

Consumer and capital goods increasingly embody a greater percentage of services. Manufacturing companies have increased their reliance on services for their inputs, and services constitute a significant portion of their outputs and revenue. Rather than thinking of manufacturing and services as separate economic activities in today’s economy, it is much more realistic and essential to think of them as having become inextricably intertwined. Manufacturing companies are now great users, producers and traders of services. It is in fact efficient services that make U.S. manufacturing more productive and give it a competitive edge in global markets. A new term, “servicification,” has been coined to describe the increasing use of services by manufacturing firms in their purchases and production, as well as their exports, pointing to the integrated role that services play in every step of the process (Swedish National Board of Trade). This is part of an overall global trend as noted in a recent OECD study on services and manufacturing which found that in the digital age, “services are part of a ‘business ecosystem’ where collaboration with customers, partners and contractors is the key to innovation and productivity.” (OECD 2017 study)

Manufacturing firms in the U.S. are buying producing more services than before. They also sell and export more services, embodied during the production process or after, as essential -sales components. The acceleration of this trend, first noted in the mid-1970s, has transformed the business of manufacturing, with implications for both competitiveness and government policy. In particular, it has become clear that the interaction between goods and services in the manufacturing sector improves productivity and contributes to job creation, economic growth and a strong competitive advantage in international trade. A policy focus on increasing competitiveness in manufacturing thus necessarily needs to focus on services as well and to view these as parts of an integrated whole.

- The importance of services in manufacturing output is growing

A strong manufacturing sector is essential for growth and productivity in the United States. But the key to competitiveness and success in manufacturing has changed. According to a study by the McKinsey Global Institute, the new era of manufacturing will be marked by highly agile, networked enterprises that use information and analytics as skillfully as they do talent and machinery to deliver products and services to global markets. The services content of this output will be high.

The US ITC describes three key drivers of the increased use of services by manufacturing firms. These include the increased geographic spread of supply chains that require ever-greater specialization; the need to cut costs and improve efficiency; and the desire to deepen and improve customer relationships by providing services related to their product (US ITC study). Utilizing services is now an essential strategy for manufacturing firms to differentiate and customize their products from competitors, including the critical need of after-sale servicing.

While services are used throughout the manufacturing process, some services such as research and development are incorporated at the beginning of the value chain, while others such as retailing, after-sales service, and maintenance and repair are relevant at the end of the chain. Still other services are needed throughout the manufacturing process at every stage, such as telecommunications and financial services, accounting and management services. On average, about one-fourth of intermediate inputs used by U.S. manufacturing firms were constituted by services in 2011; notably, this figure was much higher for certain types of products, especially electronics, where the ‘services intensity’ reached as high as 47.6 percent in manufacturing output (US ITC study). A 2017 OECD report based on a survey of OECD countries found that “Across countries between 25% and 60 % of employment in manufacturing firms is found in service support functions such as R&D, engineering, transport, logistics, distribution, marketing, sales, after-sales service, IT, management and back office support.” (OECD 2017 study)

Business services play the most important role in manufacturing. These are also the services that have grown most dynamically in the U.S. and globally. Business service providers sell the majority of their output to other firms intended as intermediate inputs into final products rather than to final consumers. Such services are wide-ranging and varied, but generally include the more highly-skilled components of the services industries, such as finance, telecommunications, professional services (legal, accounting), and computer and data-processing services, among others. Such business services have become more productive over recent years thanks to the application of changes and improvements in information technology, computer applications, and data processing.

These business services have known tremendous growth in the U.S. economy as well as globally and have propelled the positive trade balance for U.S. services exports as well. Since 1980, the share of business services in the U.S. economy has increased by 59 percent, more than double the 24 percent share increase of overall services (US ITC study based on US DOC BEA figures).

Numerous examples show us how both major multinationals and small manufacturing companies have moved to incorporate services into their output and in considerable number. The American automobile is no longer just a physical piece of machinery. While engineering, quality control and R&D have long been part of manufacturing activity, the services component in physical output has been increasing over time with the modernization of services. Now over 50 percent of the average cost of manufacturing an automobile is now compromised of services, including engineering, quality assessment and research and development, as well as many others (Stephenson & Drake-Brockman).

American electronic producers have moved very far along the scale of incorporating a high percentage of services into the products they sell. In the case of Apple, more than 50% of the iPod’s value has nothing to do with merchandise components and everything to do with services activities involved in conception, design, retail and distribution (Gereffi). The iPhone is an even stronger example where merchandise components represent less than one third of the total value of the final product, with services accounting for two thirds, though exactly how much value is added by each of the individual services components such as R&D, software development, engineering, marketing, transport, packaging and others cannot be broken down to date. Although marketed as goods and recorded as such in statistics, many electronic products are essentially services in a hard cover wrapping. And the after-sales business they generate is nearly all services.

In examining the use of services by manufacturing firms through 21 case studies, researchers found extensive and expanding use of services in a wide-range of manufacturing activities, including aircraft control systems, automotive parts and components, computer servers, printed circuit boards, construction machinery, refrigerators, power generation equipment, telecommunication equipment, watches, precision die and machine parts, and industrial welding equipment. Striking results showed that the number and range of services entering the manufacturing value chain is considerable, ranging from around 40 in the case of automotive components to 74 in the case of power plant equipment. Although it is difficult to obtain systematic information on the share of total value (cost) accounted for by these services, the figures given range anywhere from 30 to 90 percent. Thus services for most of these 21 manufacturing firms represent on average the majority component of their product’s value. A study by Deloitte cites the examples of Rolls-Royce and Xerox Corporation, for which the service business contributes more than 50 percent of total revenues. A prominent U.S. healthcare provider, Medtronic, is among the world’s largest integrated medical firms. Long known as a market leader in innovative medical technology, Medtronic now also offers services and solutions as a large part of its business package to help hospitals improve health care quality, enhance operational performance and achieve efficiency gains.

- Higher value services increasingly enhance manufacturing production value

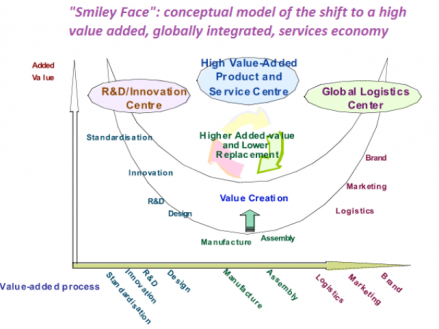

As Stanley Chih demonstrated in his famous “Smiley Face”, the highest value-added services activities such as R&D/innovation or global logistics increasingly enhance production value. This research reveals that the activities that add the most value to core production of goods are the services activities located on either side of the value chain and the manufacturing production node, from the R&D/innovation center and the logistics center, to encompass all of the value added in between coming from services activities. To improve competitiveness, manufacturing firms need to move up the value chain on either side of the production node.

Services innovation obtained through moving up the value chain is now understood as the main enabler of “multi-factor productivity” increases, which used to be the un-measurable residual in manufacturing output previously labeled as technological change (Tcha 2011).

“Smiley Face” Model of the Shift to Services

Source: Business Week Online Extra, May 16, 2005. Stan Chih of ACER Computers on Chinese Taipei and China

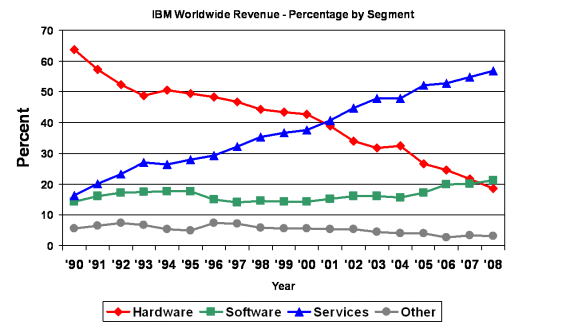

IBM Corporation provides a dramatic example of corporate transformation from manufacturing to services, with the focus at the R&D/innovation end. While the corporation initially focused on producing computer hardware, the trend in profitability for IBM has been away from manufacturing and towards services, starting in the 1990s, as illustrated below. By the millennium, focus on hardware was no longer commercially appropriate, with computer software and services increasingly dominating the group’s worldwide revenue. Corporate focus is now firmly at the “Ideation”/ services end of the value-chain, from which the majority of profits are being drawn. On its website, IBM’s focus is nearly exclusively on its services research, activity and applications (including artificial intelligence), the Internet of things, providing digital and computerized solutions for tax preparation, solar energy use, telecommunication, medical technology, and the application of cognitive computing to business processes.

IBM’s Business Transformation to “Ideation”

Source: Koomen (2009)

Manufacturing companies rely heavily on services to coordinate their integrated production sites and move intermediate goods from one production location to another in value chain structures around the world before finalization. For this, they need services to ensure that final goods are moved to all the markets where they will be sold. This increases the demand for “coordination services” such as telecommunications, transport and data flows within firms or by associated firms become the key to a company’s ability to participate in these integrated production networks (Stephenson and Drake-Brockman). The role of services in connecting the points in the goods supply chain is increasingly recognized, as are the tremendous benefits that can arise from greater efficiency in the “logistics” component of production and trade (World Economic Forum-World Bank-Bain study).

- Services bundled in traded manufactured products is growing

Services that are budled with manufactured goods contribute to the final value of the product either as inputs “embodied” during the production process (for example, energy, transport, communications, insurance, accountancy, consulting, design, advertising/ marketing, warehousing, software, legal and other professional expertise) or “embedded” at the point of merchandise sale (for example, financing, training, maintenance, repair and other after-sales services). For many manufactured goods – especially elaborately transformed, high value-added products – these services can account for a significant proportion of the final value of the goods.

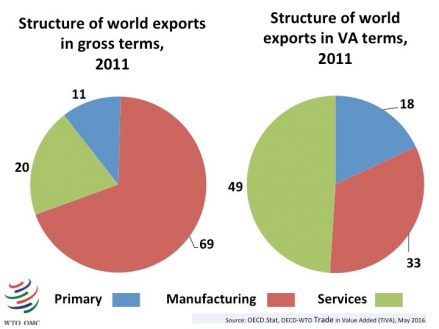

International trade statistics grossly understate the importance of services trade, given the growth of global supply chains. Traditional trade statistics do not account for the value of ‘inputted’ services into traded intermediates and final goods because customs officials attribute the full value of products to the last producer.

The ‘economy of origin’ is often only the most recent assembler in the supply chain and neither creates nor benefits from the full value of the final good, which is often spread across several economies. This means that effectively the export value of the embodied and embedded services are considered manufactured exports, thereby excluding the services input. This deficiency in statistical technique has given rise to the notion that services are not as prominent as goods in international trade. A classic example of this is the factory gate price of an iPhone recorded as US$144 in international trade when exported from China. However, less than 10 percent of this was Chinese value-added and most of that was attributable to assembly, while the majority of value for the iPhone came from U.S. design and engineering, with other services drawn from around the world (APEC study).

This picture changes dramatically when the value of these incorporated services is calculated. Adding up the “value” contributed by services to intermediate and final merchandise goods through calculating trade on a value-added basis is now possible through a new OECD and WTO database on trade. The most recent update reveals that services accounted for nearly 50 percent of the value of world trade in 2011, while manufacturing accounted for 33 percent. For many manufactured products, particularly those on the higher technology end of the scale, the value of incorporated services can be much higher than their physical components. Looking at international trade data on a value-added basis gives a more accurate picture of the importance of services as incorporated into all things traded.

Services Account for Half of World Trade on a Value-Added Basis

Services are a critically important component of U.S. trade, with 34 percent of total U.S. exports made up of services (as measured on a gross statistical basis). However, when the value of the numerous services embodied in the production of goods is considered, services represent 50 percent of total U.S. exports and 4.2 million jobs in the U.S. in 2013 (Brookings Institution).

- Services are essential to improving the profitability of manufacturing firms

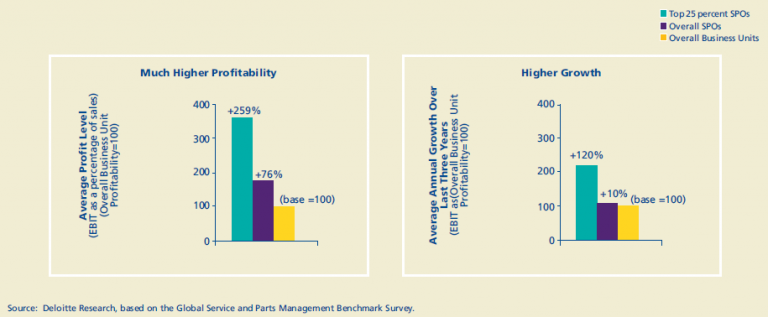

Manufacturing companies increase their use of services for two major reasons: increased efficiency and profit. An extensive study by Deloitte of 80 multinational manufacturing companies ranging from aerospace and defense and automotive to high technology and diversified manufacturing concluded that while services represented on average 25 percent of revenue for these companies, they constituted as much as 46 percent of the profits (Deloitte study). The average profitability of the service businesses surveyed was shown to be more than 75 percent higher than overall business unit profitability. The Deloitte study concludes that for many manufacturing companies today, there would be little or no profitability without their service business. The study also cites the lack of focus in many firms on “growing” the services component of their manufacturing business as one constraint on the ability of manufacturing in the U.S. and elsewhere to realize greater efficiency and profits. The services strengths of manufacturing firms can particularly improve through better strategy and business designs, operations planning and management and execution of customer service. Some companies, such as IBM, are already championing the services revolution to drive performance.

For those manufacturing companies that integrate more services into their manufacturing operations, the dividends are high, especially when observing the impact on profitability and growth. This is because services activities typically generate more profit than the primary product business. According to the Deloitte study as shown in the charts below, the average profitability of service and parts operations for the 80 firms surveyed was more than 75 percent higher than overall business unit profitability. In fact, the most profitable services businesses benchmarked within these firms were more than three times as profitable as their average business unit and were growing 10 percent faster (Deloitte study). When both the services and fast-growing service parts operations are taken together, Deloitte estimated that nearly half (46 percent) of total profits of the companies were due to the services and parts businesses.

The Impact of the Services and Parts Operation on Business Performance

(higher profitability and higher growth)

- Services and data flows improve manufacturing production efficiency

In a study examining how manufacturing contributes to economies in the 21st century, the McKinsey Global Institute examined the growing importance of services in manufacturing, changes in technology, and data flows as key factors shaping the evolution of this sector in the future. The study highlights the 30-55 percent of jobs in the manufacturing sector in advanced economies that are in fact services jobs and states that the distinction between manufacturing and services will become increasingly blurred in the future (McKinsey Global Institute study).

The basis of competence in manufacturing is shifting rapidly towards a high component of integrated service excellence. The 4th industrial revolution is already upon us, consisting of the combination of cloud computing power for big data analytics and the delivery of cloud computing power through the ‘Internet of things’. This has already begun to positively transform all aspects of production and society through the emergence of new business models. Services are at the front and center in these new models. With ‘smart’ goods now the products of choice, manufacturing companies must also be services providers by necessity. Innovations and new technologies include new materials (carbon fiber components), the application of nanotechnology, advanced robotics and 3-D printing. The cost of automation relative to labor has fallen by 40 to 50 percent in advanced economies since 1990 (MGI study). These new technologies, based on informatics and services, will lower costs and open up new opportunities for manufacturing firms.

Boeing has said that it would like to be viewed as a ‘services company’, given that services are by far the most important part of its operations. It uses computerized design and digital processes at every stage of the production/manufacture phase, with the data requirements huge in order to combine and assemble successfully the upwards of four million parts that are involved in building each airplane and the 65 million parts that go through its factories each month. All data on each part are retained for the life of each airplane, between 40 and 50 years (Russ Benson, Vice President for IT, Boeing). Producers of sporting equipment are integrating services with goods to make ‘smart’ products that will improve the skill of players by sending signals up to a cloud that will in turn communicate with advice on how to improve performance technique.

Digital services are fueling the Next Industrial Revolution (NIR), providing 25 percent of total input of manufacturing that enables improvements in manufacturing efficiency and incorporates big data analytics delivered through smart technologies. Next generation networks–5G, fiber networks–will be the enablers of the next technological revolution, creating launch pads for smart cities, education, and new means of producing manufactured goods. In this digital environment, companies have stressed that being ‘smart’ also means being connected (Tom Robertson, Vice President, Microsoft). Firms need networks that allow for free data flows, both within and between national boundaries. Assuring open borders to data flows through negotiated trade agreements is vital to American firms in the 21st century.

Data flows underpin our digitized world. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, cross-border data flows grew by 45 times between 2005 and 2014 and generated $2.8 trillion in economic value in 2014, contributing more to world GDP than global trade in goods (MGI study). Such data flows are expected to grow another nine-fold in the next five years, reflecting the tremendous digitization of the world economy. These data flows and data platforms are critical not just for large multinationals but equally for small businesses that rely on online digital platforms to connect with customers around the world (Thanos).

For manufacturing firms to become integrated services providers and move into ‘smart’ manufacturing, the free flow of cross border data as guaranteed in international trade agreements is a necessary underpinning. Information technology and data flows have become critical drivers of productivity and competitiveness in new industries as well as in long-established manufacturing industries in all states of the United States, not just Silicon Valley (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation report).

Manufacturing will continue its paradigm shift towards producing ‘smart’ products through integrating high-tech and high quality services. The distinction between manufacturing and services, already blurred, will become even stronger. Economic policy must consider and support the contribution of services in order to revitalize what will surely be a continuously transformed manufacturing sector.

[Cross-posted with permission from the author. The article is published here on America's Trade Policy's website]

Bibliography

APEC, 2015, Services in Global Value Chains: Manufacturing-Related Services, edited by Patrick Low and Gloria O. Pasadilla, World Scientific Publishers, available at http://publications.apec.org/publication-detail.php?pub_id=1677

Deloitte Research Global Manufacturing Study, 2006, The Service Revolution in Global Manufacturing Industries, available at http://www.apec.org.au/docs/2011-11_training/deloitte2006.pdf

Geferri, Gary, 2011,”Global Value Chain Analysis and its Implications for Measuring Global Trade”, Presentation at the Global Forum on Trade Statistics: WTO, Geneva

Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2016, High-tech Nation: How Technological Innovation Shapes America’s 435 Congressional Districts, available at https://itif.org/publications/2016/11/28/technation

Koomen, Karen, 2009, Head of Government Relations IBM Australia and New Zealand, “Dialogue on Business Innovation in Response to the Financial Crisis”, Annual Conference of China Association of Trade in Services Beijing, 2009

Low, Patrick, 2016, Rethinking Services in a Changing World, WEF-ICTSD E15 Policy Options Report, file:///Users/sherrystephenson/Downloads/Rethinking%20Services%20in%20a%20Changing%20World%20(2).pdf

McKinsey Global Institute, 2012, Manufacturing the Future: The next era of global growth and Innovation, available at https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/mep/data/Manufacturing-the-Future.pdf

OECD-WTO Initiative, Measuring Trade in Value-Added, available at http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/measuringtradeinvalue-addedanoecd-wtojointinitiative.htm

Stephenson, Sherry and Jane Drake-Brockman, 2014, The Services Trade Dimension of Global Value Chains: Policy Implications for Commonwealth Developing Countries and Small States, with Jane Drake-Brockman, Commonwealth Trade Policy Discussion Paper No. 4, (ISSN 2313-2205), Commonwealth Secretariat, 2014. Available at http://www.thecommonwealth-ilibrary.org/commonwealth/trade/commonwealth-trade-policy-discussion-papers_23132205

Stephenson, Sherry, 2014, Global Value Chains: The New Reality of International Trade, Geneva: E15 Initiative, World Economic Forum -ICTSD, Available on the ICTSD E15 website at

http://e15initiative.org/publications/global-value-chains-the-new-reality-of-international-trade/

Stephenson, Sherry and Jane Drake-Brockman, 2012, Implications for 21st Century Trade and Development of the Emergence of Services Value Chains, ICTSD Working Paper, available at http://ictsd.org/downloads/2012/11/implications-for-21st-century-trade-and-development-of-the-emergence-of-services-value-chains.pdf

Stephenson, Sherry, 2012, Services and Global Value Chains, in “The Shifting Geography of Global Value Chains: Implications for Developing Countries and Trade Policy”, available at

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GAC_GlobalTradeSystem_Report_2012.pdf

Swedish National Board of Trade, 2013, Everybody is in Services, Kommerskollegium Policy Paper, available at http://www.kommers.se/Documents/dokumentarkiv/publikationer/2012/skriftserien/report-everybody-is-in-services.pdf

Swedish National Board of Trade, Global Value Chains and Services, 2013, available at http://www.kommers.se/In-English/Publications/2013/Global-Value-Chains-and-Services/

Paul Thanos, The Case for Services Trade, Wilson Center, Washington DC, January 2017, available at https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/the-case-for-services-trade

US ITC, 2013, Recent Trends in U.S. Services Trade 2013 Report: “Services Contribution to Manufacturing”, Publication number 4440, available at https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4440c.pdf

Miroudot, S. and C. Cadestin (2017), Services in Global Value Chains: From Inputs to Value-Creating Activities”, OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 197, OECD Publishing, Paris..

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments