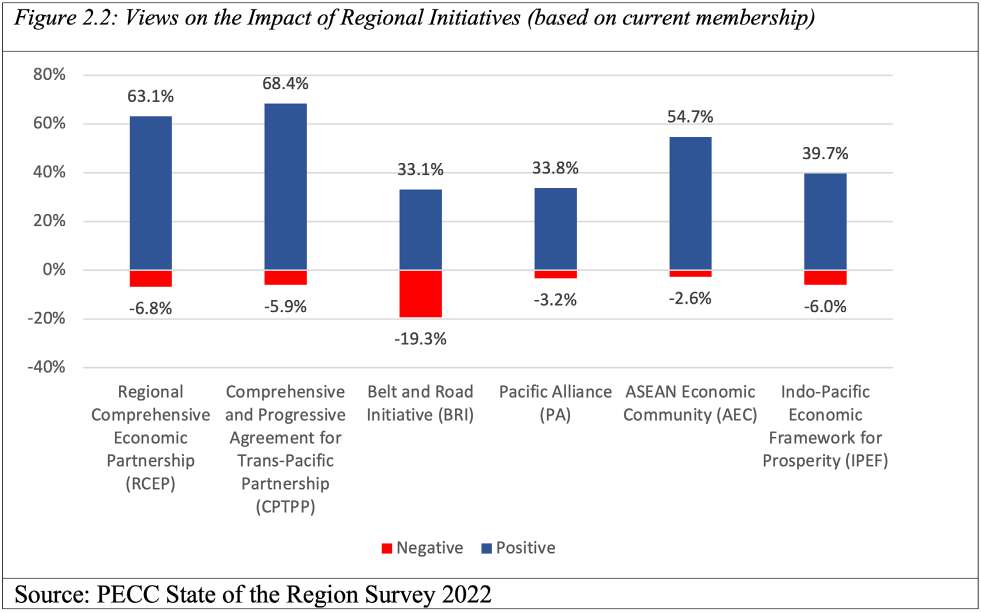

The trend toward regional cooperation in Asia that picked up steam beginning in 2000 was mainly characterized by bilateral FTAs, consistent with what was happening elsewhere in the world. Globally, in 2000, there were 100 in force; today, there are 354.11 In Asia the growth rate of FTAs has been even more rapid, with the number of FTAs growing from 39 to 185 over the same period.12 The notable exception to the bilateral trend is ASEAN, which began the process of forming a subregional FTA in 1992 and built upon that to create the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), which technically went into effect in December 2015 but continues to deepen under the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2025. The AEC aims to create a region in which goods, skilled labor, and FDI would flow freely, and where there would be greater freedom of movement of capital.13 The economic effects of the AEC were estimated to be large at 5.3% of ASEAN GDP on a permanent basis (Petri, et. al. 2012). A majority (55%) of respondents to the PECC 2022 Survey believe that the AEC is having a positive or very positive impact on their economy, an impressive response given that ASEAN is relatively small, e.g., only two-fifths the size of the Chinese economy.14

Bilateral FTAs do tend to deliver positive results as well, depending of course on the agreement. But the proliferation of bilateral FTAs has obvious drawbacks: the agreements feature different sectoral coverage, standards, degrees of economic liberalization, and rules of origin, for example. Some economists claim that such an approach is not only inefficient but actually could be detrimental to multilateral trade liberalization (or “stumbling blocs”)15. Consolidating these agreements under a region-wide umbrella would clearly be more efficient. Hence, the region started to pursue “megaregional” approaches to economic integration, beginning with the TPP in January 2008 and then RCEP beginning in November 2012.

Gains from regional economic cooperation are by no means guaranteed: they will be a function of, inter alia, the size and depth of the agreement, complementarity and competitiveness of the integrating economies, and economic structure of the participants. By their very nature these arrangements are discriminatory in favor of member economies, which in turn could lead to trade diversion and other efficiency-sapping results. Hence, empirical estimates of these FTAs are necessary to grasp whether they make sense economically.

Economists have favored the use of Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models to estimate the effects of trade agreements on income, trade, sectors, factor returns, and, sometimes, employment. Below we summarize studies estimating the effects of RCEP, CPTPP and its potential enlargement, and the FTAAP. But to begin, it is important to note that while RCEP and CPTPP have entered into force— and any enlargements would keep the CPTPP template—it is unclear what exactly the FTAPP will look like. We consider that question in the next section.

In the literature a number of CGE studies have anticipated the potential economic effects of Asia-Pacific megaregional accords. For example, Li et al. (2017) and Monetary Authority of Singapore (2021) estimate the effects of RCEP; Petri, et. al. (2021) focuses on CPTPP; and Ferrantino, Maliszewska, and Taran (2020) and Park, et. al. (2021) (discussed below) estimate the effects of both. Kawasaki (2014) and Park et al. (2010) focus on the FTAAP, configured as an FTA based on APEC membership, as does Petri, et. al. (2012) (discussed below). An overview of how CGE models work can be found in Park, et. al., 2021. Below we summarize some main lessons and takeaways from this research.

Overall, the literature suggests positive welfare gains for all major FTAs in the Asia-Pacific region, meaning that trade creation dominates trade diversion, efficiency improves, and welfare increases for integrating economies. Gains tend to be relatively small if only tariff reductions are included in the model but much larger when non-tariff barriers are modelled, and firm-heterogeneity is specified. Usually, exports propel the increase in income, which is intuitive given that the parametric changes relate mostly to trade variables. For example, in Petri and Plummer (2016), exports grow about twice as fast as income for both the TPP and CPTPP scenarios, suggesting an important increase in regional integration. Depth and size also matter; deeper integration templates like the CPTPP generate far larger results, ceteris paribus, and the larger the number and size of the economies, the greater the welfare effects. In Petri et al. (2017), a CPTPP scenario that includes the eleven original members and enlargement to add five additional economies that had expressed interest in joining the CPTPP (i.e. Indonesia, Korea, the Philippines, Thailand, and Chinese Taipei), generates income gains that are 50 percent larger than RCEP, mainly due to a deeper liberalization template. Gains from the FTAAP are much larger than the TPP due to its being a more inclusive agreement.

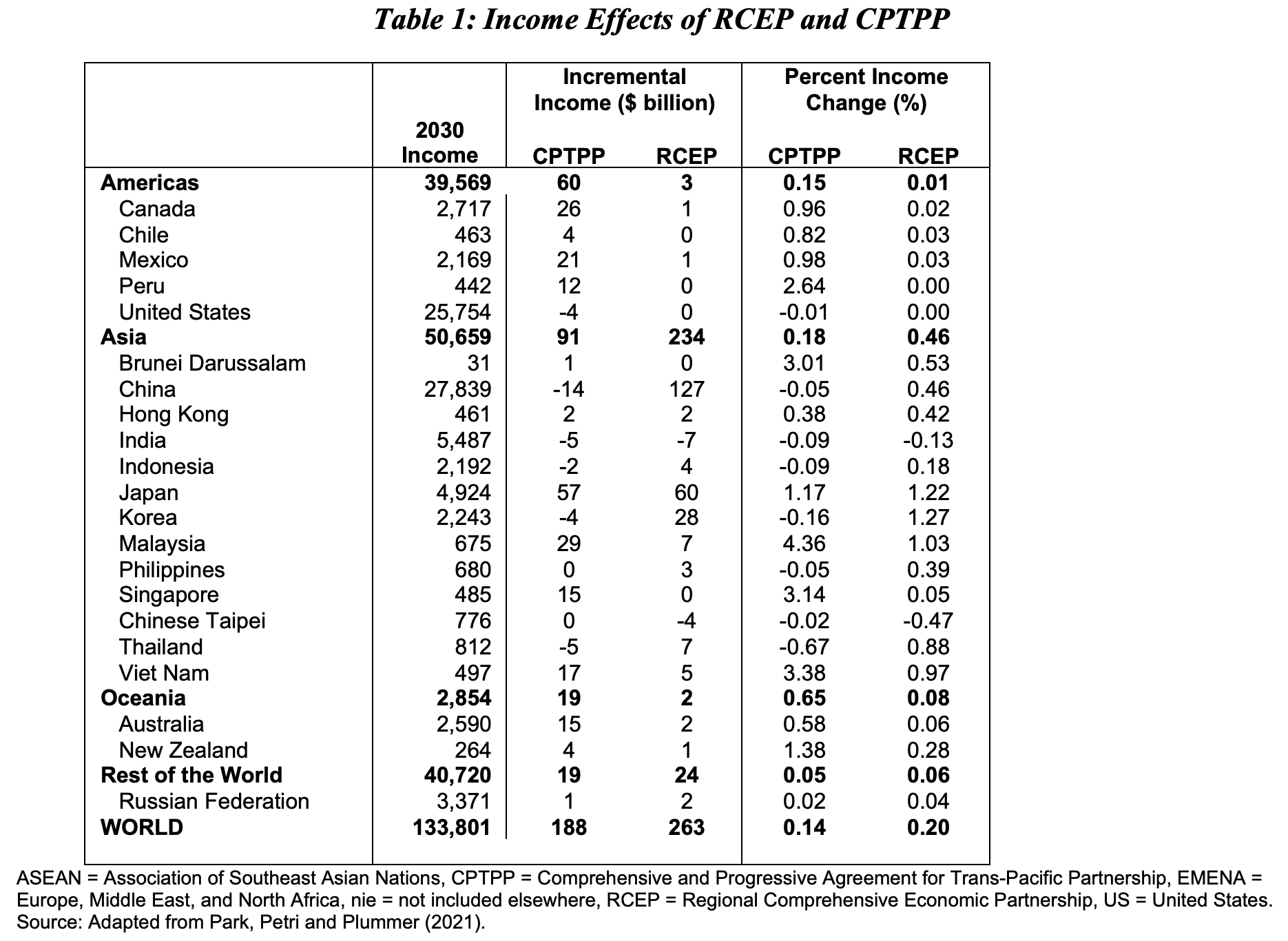

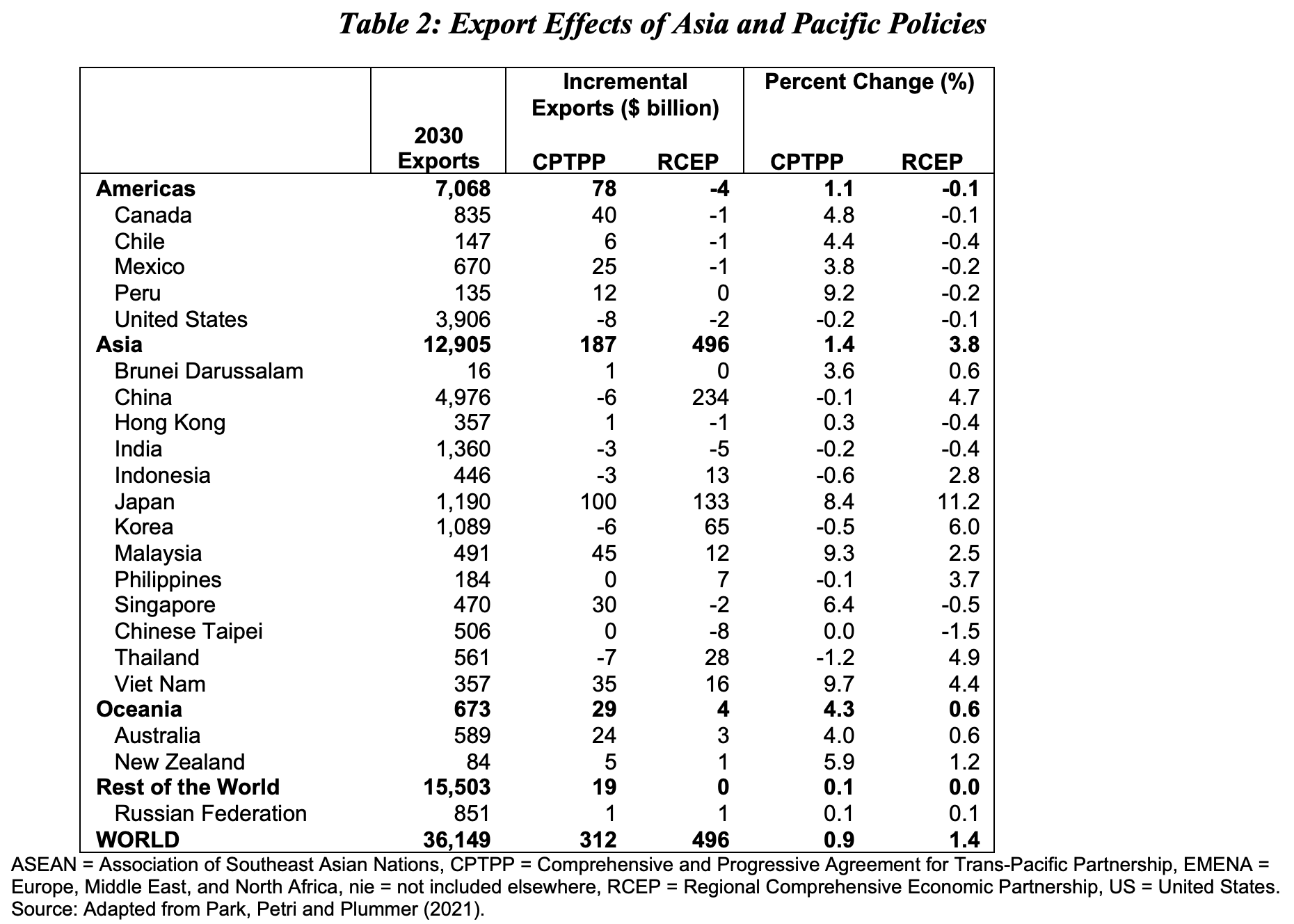

Park, Petri and Plummer (2021) is a recent CGE study that applies a cutting-edge CGE model and includes the actual template of the 15-member RCEP agreement and the 11-member CPTPP in its estimates. The implications for changes in aggregate income and trade are shown in Figure 2.2 and Figure 2.3 with further details provided in Tables 1 and 2. These tables show effects in incremental terms, that is, the amount that each scenario adds to (or subtracts from) previous policies and is expressed relative to baseline projections for 2030. This study shows that the benefits of the RCEP agreement could be substantial, particularly for Northeast Asia. While less comprehensive than the CPTPP, RCEP is estimated to generate global income gains that are two-fifths more than the CPTPP, due to its larger scale.

Indeed, Japan, a member of both the CPTPP and RCEP, will gain about as much from the latter as the former. The negative income effect on excluded economies under both agreements will be minimal; China is the biggest loser under the CPTPP (-$14 billion), but that is only five-tenths of one person of Chinese agreement income in 2030. India loses the most under RCEP but, again, it is small compared to the size of the Indian economy. Trade effects follow similar patterns with interesting differences: The increase in exports under the CPTPP and RCEP are 60% and 53%, respectively, which exceeds the increase in income in both cases, a typical result in CGE modeling. Relative to total exports, Vietnam gains the most under CPTPP (9.7%) and Japan gains the most under RCEP (11.2%). Trade diversion is small under both scenarios, with only two economies experiencing greater than a 1% hit, that is, Thailand (-1.2%) under CPTPP and Chinese Taipei (-1.5%) under RCEP.

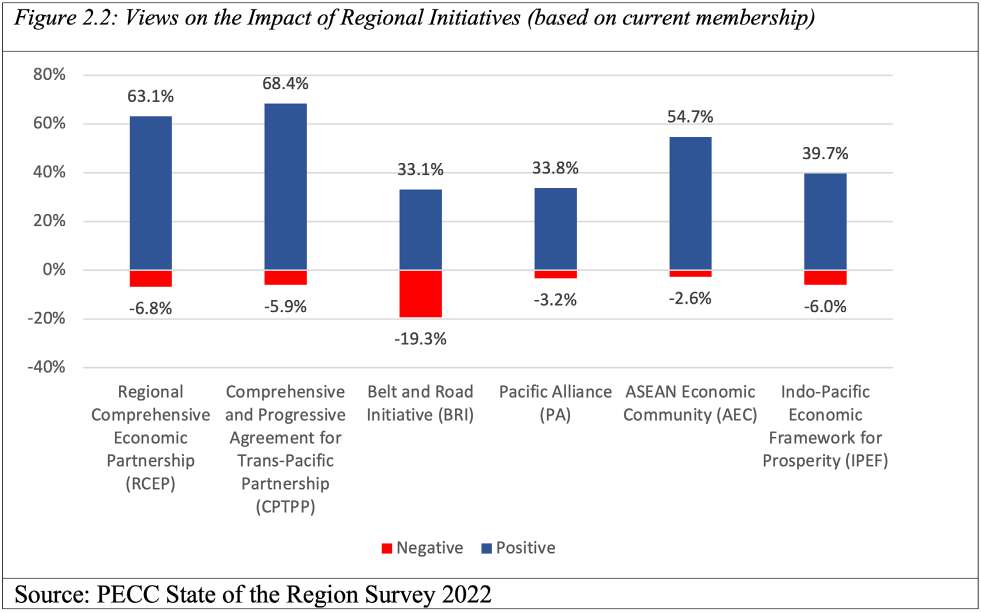

The 2022 State of the Region survey also asks respondents how they believe the CPTPP and RCEP will affect their economy by 2030, as well as the AEC, IPEF, Pacific Alliance, and the Belt and Road Initiative (Figure 2.2) . Very few (less than 7%) believe that the CPTPP or RCEP will have a negative or very negative effect on their respective economies, while about two-thirds (68.3% and 63.1% for CPTPP and RCEP, respectively) anticipate that the implications will be positive or very positive.

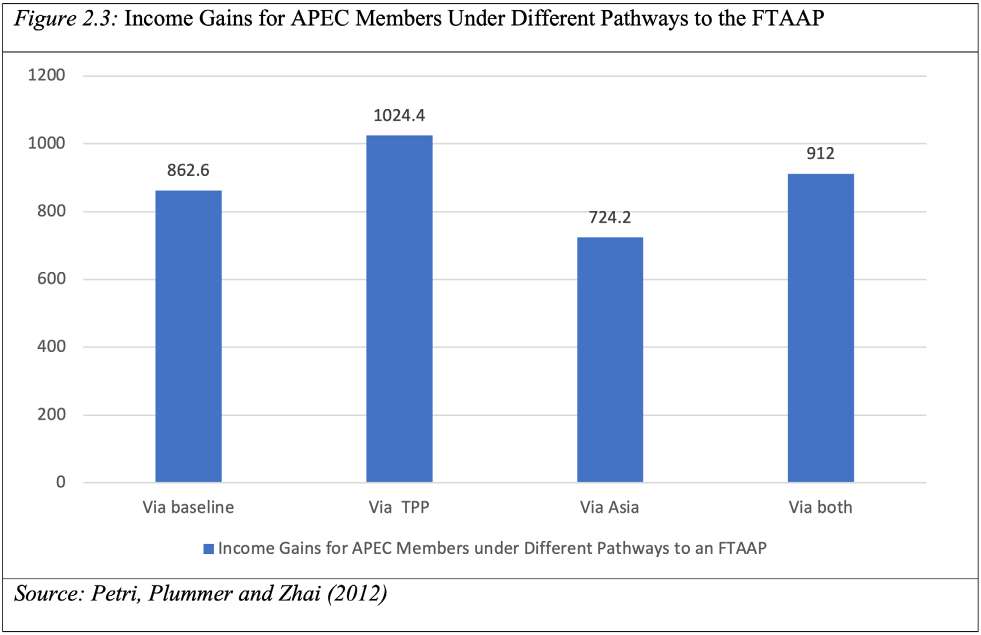

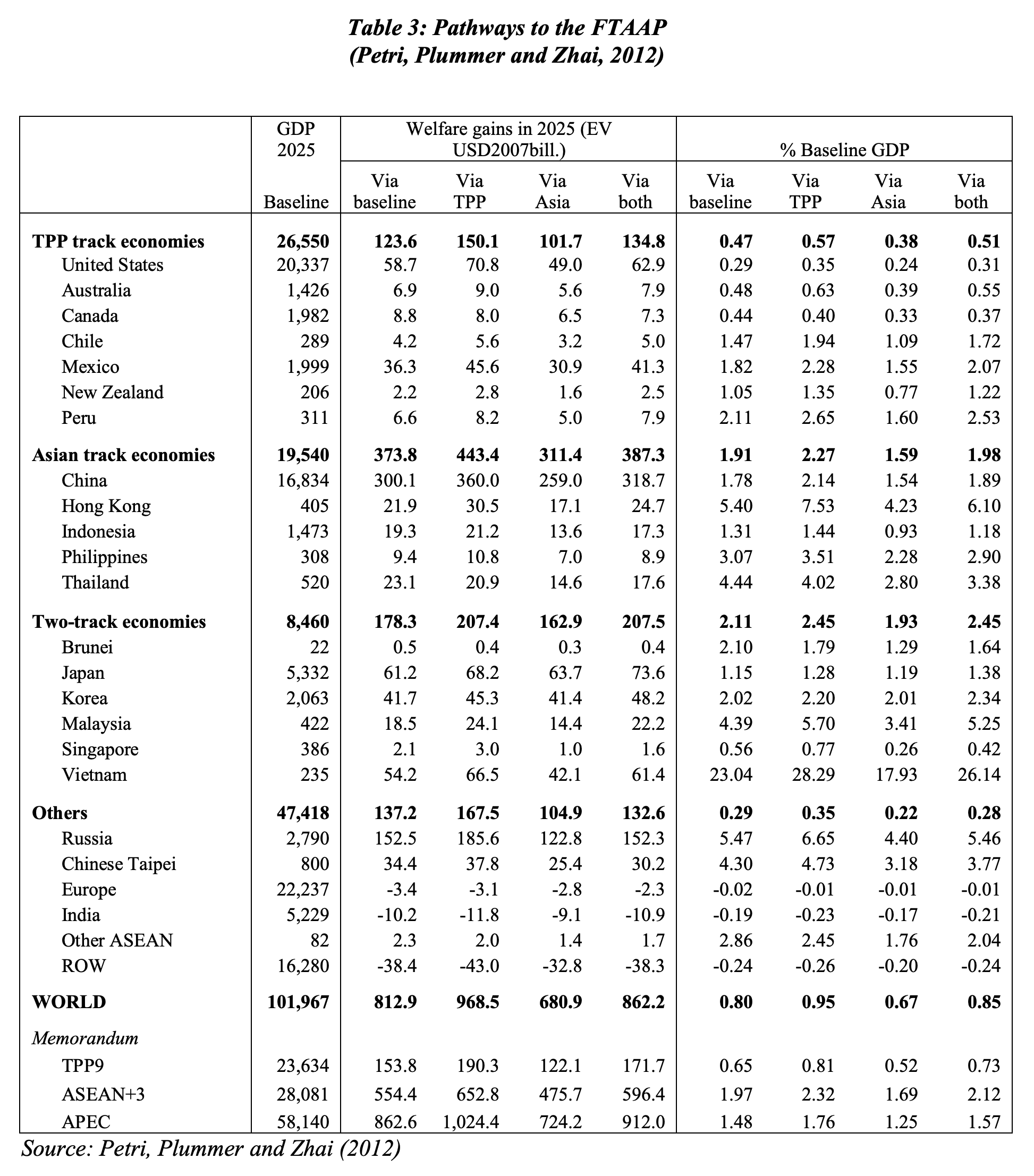

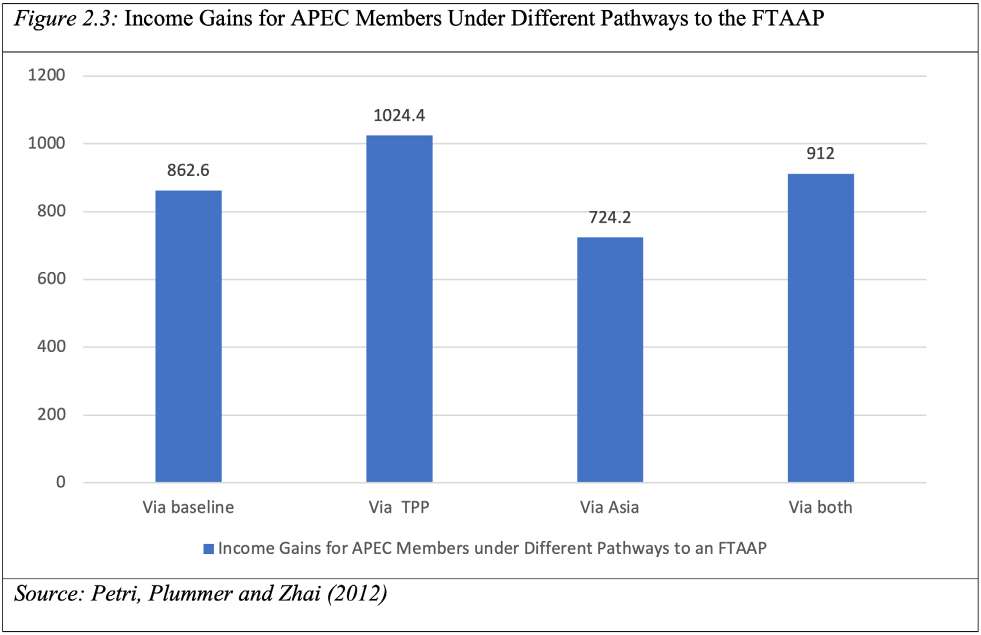

As noted above, while we do have the text of the CPTPP and RCEP agreements, it is unclear what the FTAAP template would look like. This obviously makes estimation difficult. However, an earlier study of the FTAAP and associated pathways (Petri, Plummer and Fan 2012) estimates the effects of the FTAAP using a TPP-pathway template (based on the US-Korea FTA agreement, an advanced agreement at the time); an “Asian track” that includes ASEAN economies (save Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Myanmar), Northeast Asia (China, Korea and Japan) and Hong Kong, China based on an “ASEAN+1” template; and an average of both. The results are presented in Figure 2.5 and Table 3. Several important conclusions emerge. First, regardless of the template, the gains from the FTAAP to APEC members are likely to be large overall, ranging from $1,024 billion for APEC members under the TPP template to $724 billion under the Asian template. Both are significant increases if one keeps in mind that the gains relate to a permanent increase in efficiency. Second, the depth of the FTAAP template makes a great deal of difference, with TPP template gains being more than two-fifths higher than the Asian template. Third, while the gains are not evenly distributed, the welfare of all member-economies increases, with small, open economies tending to gain the most. Finally, the results are driven to no small degree by membership of the United States and China, the two largest economies in the world, opening their markets to each other under the FTAAP. In fact, together they account for over 40% of the nominal gains in all scenarios.

In sum, the megaregional literature underscores several key lessons that are generally applicable. First, bigger is better: ceteris paribus, the larger the agreement, the greater (less) the potential for trade and investment creation (diversion) as well as various dynamic effects of regional integration such as economies of scale. Second, deeper is better: the more comprehensive the agreement, the greater the gains from economic integration. In particular, the inclusion of non-tariff measures and nonborder, trade-related policy issues generate far larger gains because today they constitute the most significant impediments to trade at the border, and non-border issues restrict everything from FDI flows to interaction in ‘21st century’ areas (e.g. digital trade, innovation). Third, the more open the agreement and the greater the spill-over effects of liberalization, the larger the gains for both partner and non-partner countries. These lessons all suggest that pursuing the Yokohama Vision continues to make economic sense, and building it based on the CPTPP would generate the most gains. Still, while RCEP is not as deep as the CPTPP, it deliberately left room for improvements. For example, it did not impose full disciplines on members at early stages of development by providing several flexibility clauses. But even the least developed members will begin to adopt RCEP’s framework once the agreement enters into force and, in time, will need to pursue its full for integration mandate. There may be lessons here in configuring the FTAAP.

III. Modalities to Achieve the FTAAP: The Way Forward

The concept of FTAAP among the 21 APEC member economies began to be discussed in 2006, based on a proposal by the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC).16 As noted above, discussions regarding the FTAAP have focused on the TPP/CPTPP and RCEP as pathways—and, more recently, the Pacific Alliance, which is a group of four Latin American countries, three of which are in the CPTPP—to a wider regional accord, but it is unclear as to how this will happen. Building on existing agreements such as the CPTPP or RCEP offers the advantage that many economies will have already agreed to their terms and should facilitate the creation of a common template for an FTAAP accord.

The CPTPP offers a cutting-edge, deep liberalization template, well beyond what RCEP has agreed to thus far (it is a living agreement and can deepen over time). Still, RCEP has proven itself to be effective in formulating a meaningful agreement while at the same time accommodating a very diverse group of economies. Hence, the FTAAP could allow departures from the high CPTPP standards in order to expand its membership, while permitting members to benefit from existing accords. Such arrangements could lead to a multi-tiered system of rules, such as those that have emerged under the WTO. As in the WTO, members would be obligated to follow baseline commitments, but could then assume additional obligations under more ambitious agreements such as the CPTPP. Such umbrella or hybrid approaches have been proposed by Petri and Raheem (2014) and Schott (2014).

In the past, most economic analysis has focused on a “single undertaking” of the FTAAP, as has been traditional in the creation of FTAs, including RCEP and CPTPP. But in the current environment, this approach is proving difficult, particularly since the largest economy in the region, the United States, has opted out of these megaregional schemes so far and instead has launched the “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework” (IPEF) featuring a number of trade facilitating and harmonization policies but excluding market access, a key component of any FTA. This exclusion of market access is no doubt a reason why, in responses to PECC 2022 Survey question 12, only 10% thought that the effects of IPEF would be very positive, despite the fact that the US market is so large. It may be that a more modest approach to building the FTAAP by harmonizing sectoral agreements already included in CPTPP and RCEP would have advantages by working at the sectoral level. As the CPTPP and RCEP harmonize rules and policies as well as offering greater market access, a process of building the FTAAP from the ground up through sectoral initiatives could be an option. Variable geometry may be necessary as a means to continue to move forward in these challenging times.

The results of the PECC 2022 Survey regarding views on the FTAAP generally support proceeding along both lines (question 10). A majority (59%) of respondents agree or strongly agree that the best way to achieve the FTAPP would be “through the eventual convergence in terms of product coverage and level of liberalization in various regional agreements in the region,” while the same percentage agrees that the best way forward is for APEC economies to eventually join the CPTPP (only 47% believe that this should be done via expanding RCEP). Importantly, a minority of respondents believe that the best way to proceed would be to launch separate FTAAP negotiations among interested parties, which had been the original idea of the FTAAP.

If the choice is to build the FTAAP up from the sectoral level, it will be important for the negotiating members to prioritize. The PECC 2022 Survey gives insight into which sectors should receive the most attention. More than half of the respondents gave the highest priorities to chapters on trade in services, electronic commerce, investment, trade in goods, technical barriers to trade, transparency and anti-corruption, and cooperation and capacity building. But many other sectors received a top importance rating by more than 40% of the respondents. The sectors with the lowest top-priority responses were government procurement, state-owned enterprises, and trade and gender.

In short, the survey would suggest that, since the CPTPP and RCEP regional pathways have already come into effect, the best way forward towards the FTAAP would be via enlargements of the CPTPP on the one hand, but also to harmonize policies across these two megaregionals. Indeed, this is already happening. The CPTPP is evaluating the applications of several additional APEC members (China, South Korea, Chinese Taipei) with others having expressed interest in joining and will likely apply over the next few years (e.g., Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand). If these economies come to join the CPTPP, they will cover 17 out of 21 APEC economies.

16 ABAC continues to be a strong supporter of FTAAP. For example, its 2022 Work Programme includes “progressing pathway agreements toward the realization of FTAAP” and it has sponsored several studies on the realization of the FTAAP, including on FTAAP Competition Policy (Navarro 2021) and an update on FTAAP opportunities (Plummer, et. al., 2018)

IV. Conclusions

Economic cooperation in the Asia-Pacific has come a long way. The CPTPP and RCEP constitute milestone agreements that the world is seeking to emulate: chapters from the CPTPP are being adopted by other trade agreements, and megaregional agreements in the Asia-Pacific region inspired the Africa Continental Free-trade Area, which came into force in 2021. Indeed, the agreements offer lessons for multilateral trade liberalization: in many ways the CPTPP demonstrates what is required of a modern, 21st century trade agreement and RCEP shows how the interests of developed and developing economies can be accommodated in a “living agreement” that can allow for deepening overtime. Moreover, the agreements are open to participation from non-regional economies; for example, the CPTPP is considering applications from Europe (United Kingdom) and South America (Ecuador). The economic effects of both agreements are estimated to be significant for the integrating economies with only marginal negative effects on some non-members. In fact, even economies excluded from the CPTPP and RCEP sometimes gain, as various aspects of trade and investment liberalization in the context of an FTA are per force nondiscriminatory (e.g., trade facilitation).

Nevertheless, the integration project is incomplete: the FTAAP continues to be a key goal strongly supported by APEC-based regional organizations such as ABAC. The economics certainly favor an outward-oriented, region-wide agreement like the one envisioned at the 2010 Yokohama APEC Leaders Meeting using the most advanced template possible, currently offered by the CPTPP. Respondents from the PECC 2022 Survey strongly support continuing along the pathways to the FTAAP.

This Chapter notes that there are alternative approaches to reaching the FTAAP, one that involved making the two pathways more compatible in terms of sectoral coverage and depth and the other that involves converging to the FTAAP via enlargements of the pathways. We note above that there are six APEC economies who have already expressed interest in joining the 11-member CPTPP, which would make it an agreement of 17 out of 21 APEC economies. A return of the United States to the CPTPP would be essential, but unfortunately that is difficult to imagine in the short-term. Still, the strategic and economic benefits of staying actively engaged in Asia-Pacific economic integration could be a strong pull. And given that the RCEP agreement has built into it the possibility of improving its template, these processes can be done simultaneously.

Unfortunately, while the economics favor the realization of the FTAAP whatever the process, the politics do not. As noted above, geopolitical, economic and policy uncertainties are rendering ambitious approaches to economic cooperation difficult at all levels. Ongoing conflict in the areas of technology and US-China relations, inward-looking industrial policy, and a populist backlash against globalization are creating strong headwinds.

Hence, APEC leaders will have their work cut out for them in November. But the potential gains from working toward the creation of “open, dynamic, reliant and peaceful Asia-Pacific Community” are high not only for the region but for the world.

References

Baldwin, Richard E., and Elena Seghezza, 2010. “Are Trade Blocs Building or Stumbling Blocs?,” Journal of Economic Integration, Vol. 25 (2), June, pp. 276-297.

Ferrantino, Michael Joseph, Maliszewska, Maryla, and Taran, Svitlana. 2020. “Actual and Potential Trade Agreements in the Asia-Pacific.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9496.

Kawasaki, Kenichi, 2014. The Relative Significance of EPAs in Asia-Pacific, PECC Secretariat, 26 September, Available at: https:// www.pecc.org/resources/trade-and-investment-1/2119-pecc-uibe-ftaap-ken-kawasaki

Li, Q., R. Scollay, and J. Gilbert (2017), ‘Analyzing the effects of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership on FDI in a CGE framework with firm heterogeneity’, Economic Modelling, 67(C), pp.409–420.

Monetary Authority of Singapore. 2021. Macroeconomic Review 20 (1): 25–34.

OECD, 2022. Economic and Social Impacts and Policy Implications of the War in Ukraine, OECD Economic Outlook Interim Report, March. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/economy/Interim-economic-outlook-report-march-2022.pdf

OECD and WTO. 2013. AID FOR TRADE. Paris: OECD. Park, Cyn-Young, Peter A. Petri, and Michael G. Plummer, 2021. “The Economics of Conflict and Cooperaiton in the AsiaPacific: RCEP, CPTPP, and the US-China Trade War,” East Asian Economic Review, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 233-272. Available at:

https://www.eaerweb.org/selectArticleInfo.do?article_a_no=JE0001_2021_v25n3_233&ano=JE0001_2021_v25n3_233

Petri, Peter A., and Michael G. Plummer. 2016. “The Economic Effects of the Transpacific Partnership: New Estimates.” Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper WP 16 2. https://www.piie.com/publications/wp/wp16–2.pdf

Peter, Peter A., Michael G. Plummer, and Fan Zhai, 2012. “The Economic Impact of the ASEAN Economic Community: An Applied General Equilibrium Approach,” Asian Economic Journal, Vol. 26 (2), 2012, pp. 93-118.

Petri, Peter A., Michael G. Plummer, and Fan Zhai. 2012. The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment, (Peterson Institute for International Economics, November 2012).

Petri, Peter A., Michael G. Plummer, Shujiro Urata, and Fan Zhai, 2021. “The Economics of the CPTPP and RCEP: Asia-Pacific Trade Agreements without the United States,” Chapter 2 in Cassey Lee and Pritish Bhattacharya (eds.), Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership: Implications for Southeast Asia, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2021 (with P.Petri, S.Urata and F.Zhai).

Schott, J. J. (2014). Asia-Pacific Economic Integration: Projecting the Path Forward. In G. Tang & P. A. Petri (Eds.), New Directions in Asia-Pacific Economic Integration (pp. 246–253). Honolulu: East-West Center.

Stone, Susan, and Ben Shepherd. 2011. “Dynamic Gains from Trade Equipment Imports,” OECD Trade (110) mimeo.

Wacziarg, Romain, and Karen Horn Welch. 2008. “Trade Liberalization and Growth: New Evidence.” World Bank Economic Review 22 (2): 187–231. doi:10.1093/wber/lhn007.

World Bank, 2015. Global Economic Prospects. Washington D.C.: World Bank.